Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir

BWV 029 // For the Council Election

(We give thee thanks, God, we give thee thanks) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpets I-III, percussion, bassoon I+II, strings, organo obbligato and continuo

The annual service on St Bartholomew’s Day to inaugurate the new town council numbered among the highlights of the festive calendar in Leipzig. Despite Bach’s turbulent relationship to the council – his employer – he dutifully composed the requisite cantata throughout his tenure. Some five compositions written for this occasion have been preserved in whole or in part, and the texts for a further three have also survived. Although the cantatas for this occasion have a courtly finesse, this is less a testament to the (limited) power of the Leipzig burgher class than to their career-driven interest in pleasing the Dresden territorial sovereign.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Soprano

Julia Sophie Wagner

Alto

Roswitha Mueller

Tenor

Bernhard Berchtold

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz

Choir

Soprano

Mirjam Berli, Olivia Fündeling, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Damaris Rickhaus, Simon Savoy, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Raphael Höhn, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Valentin Parli, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Monika Altorfer, Martin Korrodi, Olivia Schenkel, Marita Seeger

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Zimmermann

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Dominik Melicharek, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Pavel Janecek

Timpani

Martin Homann

Organo Obbligato

Tobias Lindner

Harpsichord

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Meinrad Walter

Recording & editing

Recording date

08/23/2013

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 2

Psalm 75:2

Text No. 3–7

Poet unknown

Text No. 8

Königsberg, 1548

First performance

27 August 1731

In-depth analysis

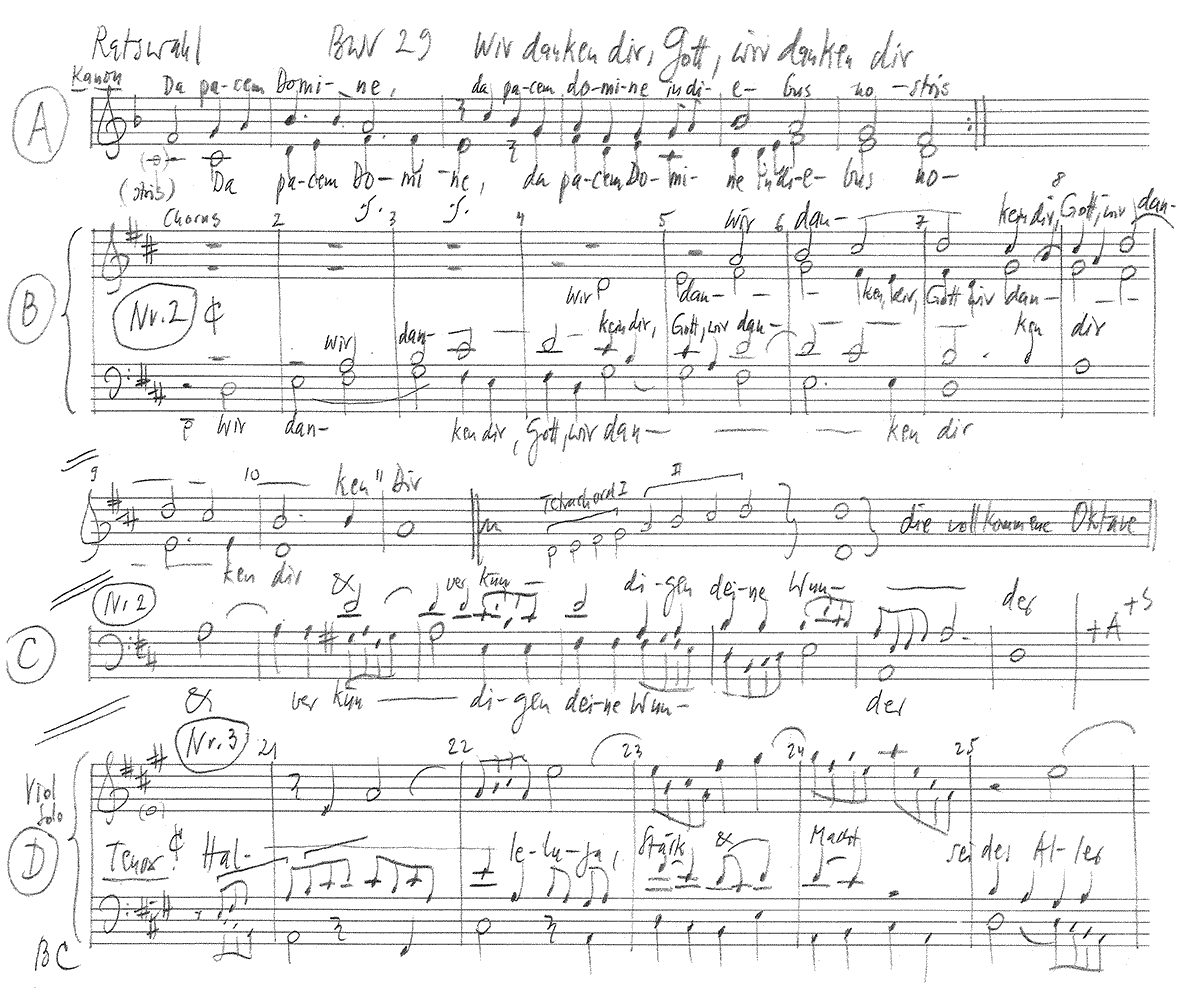

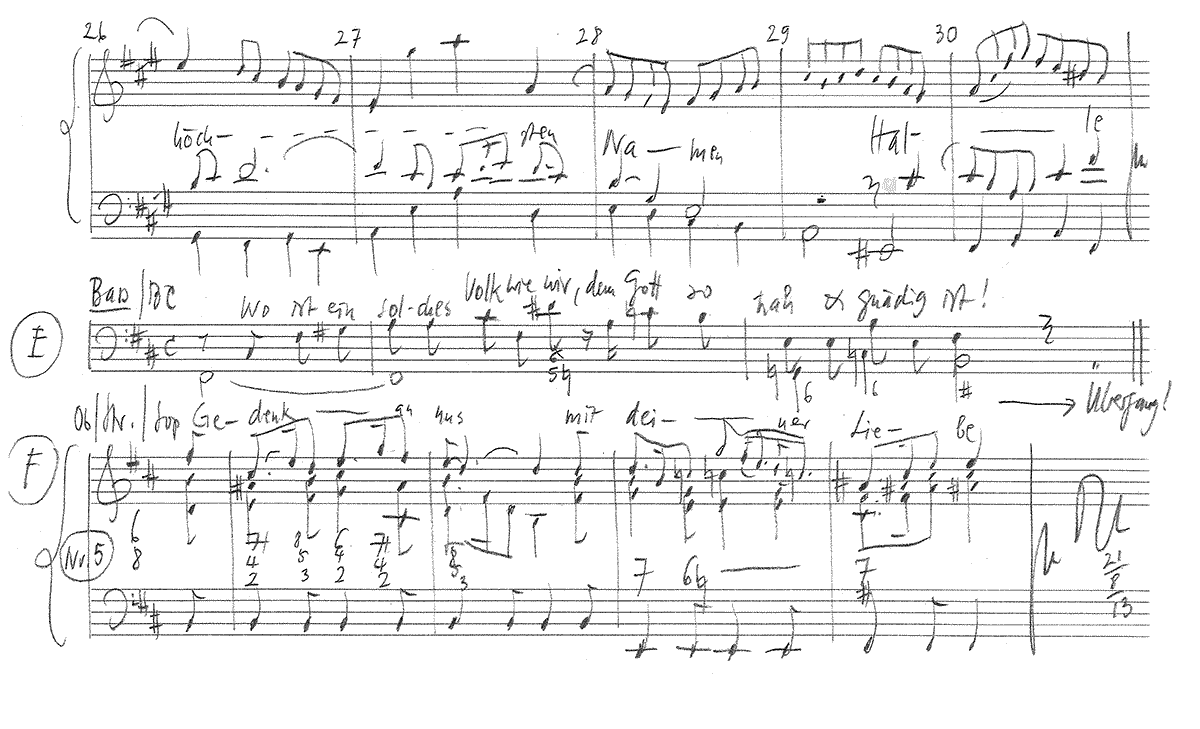

Cantata BWV 29 was re-performed several times after its premiere in 1731, and its introductory sinfonia is an impressive example of how the requirements of a specific event inspired Bach to further develop his ideas. First conceived in 1720 as the Preludio to his Partita for Violin in E Major (BWV 1006), Bach reworked the movement around 1729 for a wedding cantata, forming it into a concerto-style setting for organ and string orchestra, possibly with oboes. For the council election in 1731, trumpets and timpani were then added, lending it the exhilarating character that later inspired Felix Mendelssohn to write a piano arrangement of the movement in 1840. This transformation from a delicate solo setting into a compact orchestral movement demonstrates Bach’s mastery of motivic combination and instrumentation: first, strings and woodwinds take on the melody of the solo setting, while the addition of trumpets introduces fanfares; developmental elements and polychoral effects are then added to round out the concerto-style structure. The inclusion of an organ lends a sacred tone to the sinfonia, which together with the subsequent chorus calls to mind a St Cecilia composition dedicated to the praise of church music. This succession of a concertante-modern instrumental setting and a strict vocal fugue in early dacappella style constitutes a double prelude in which the combination of old-fashioned constancy and splendid grandeur reflects central attributes of the council. The two short text components glorifying God are captured by Bach in two contrasting themes; this music was then later reworked in 1733 for a setting with practically the same text, the Gratias of the Mass in B Minor, and later again for his Dona Nobis Pacem, which is by far the more famous today. Overall, the composition is remarkable for the successive development of its tonal scope, which, like the ascending figure of the closely controlled motive on the words of thanks, lends the work suggestive power.

By way of contrast, the light-footed tenor aria, set in the bright key of A major, unites a heroic attitude with cantabile elements. With the running “Hallelujah” figure, the soloist makes an effective entry; the libretto, by placing glorification of God above praise of the authorities, establishes a clear hierarchy. The mention of “Zion” in the middle section then introduces the ideal of a Christian community – one in which God himself would happily live.

The bass recitative takes this thought further by presenting God’s protection as the cornerstone of a good life. This general wellbeing is also owed to wise city governance, and Psalm 85 alludes to the council’s obligation to preserving peace and justice. These words of flattery are followed by the soprano aria, an intimate plea for mercy from which both rulers and servants should benefit in equal measure. Set in a flowing 6⁄8 metre and earnest B minor key, the aria conjures a magic (reminiscent of Handel’s operas and some Passion arias) that attains even greater lightness through the frequent tasto solo instruction for the organ.

Nonetheless, the libretto – as appropriate for a city of trade – also has commercial elements; in the alto recitative, the Highest is urgently implored to protect the prosperity of the community in return for praise and sacrifice. After this ceremonial declaration, the choir, representative of the people, concludes with a unison “Amen” – an acclamation in which the political contract is publicly renewed. In the ensuing alto aria, however, the gravity of the situation dissolves; the “Hallelujah” music, based on the tenor aria, gives rise to a liberated song of thanksgiving. By using the organ in place of the violins in this setting, Bach establishes a theological connection to the opening sinfonia.

“Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren” (Now laud and praise with honour): this hymnal chorale with powerful tutti winds is a succinct expression of confidence under the aegis of the divine Trinity. Although the change in council membership was nothing more than a regular rotation within the patrician class, and thus little more than an early example of a managed democracy, Bach’s imaginative composition leaves no doubt as to the significance of this supplicatory church service in renewing the community’s covenant with God. Indeed, it is successful events such as these that probably helped Bach retain his position as Stadtkantor long after his serious rift with the council in 1729/30.

Libretto

1. Sinfonia

2. Chor

«Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir

und verkündigen deine Wunder.»

3. Aire (Tenor)

Halleluja, Stärk und Macht

sei des Allerhöchsten Namen.

Zion ist noch seine Stadt,

da er seine Wohnung hat*,

da er noch bei unserm Samen

an der Väter Bund gedacht.

*da er Lust zu wohnen hat

(abweichende Lesart in Takt 117/19)

4. Rezitativ (Bass)

Gott Lob! es geht uns wohl!

Gott ist noch unsre Zuversicht;

sein Schutz, sein Trost und Licht

beschirmt die Stadt und die Paläste;

sein Flügel hält die Mauern feste.

Er lässt uns aller Orten segnen;

der Treue, die den Frieden küsst,

muss für und für

Gerechtigkeit begegnen.

Wo ist ein solches Volk wie wir,

dem Gott so nah und gnädig ist!

5. Arie (Sopran)

Gedenk an uns mit deiner Liebe,

schleuss uns in dein Erbarmen ein.

Segne die, so uns regieren,

die uns leiten, schützen, führen,

segne, die gehorsam sein.

6. Rezitativ (Alt, Chor)

Vergiss es ferner nicht, mit deiner Hand

uns Gutes zu erweisen,

so soll dich unsre Stadt und unser Land,

das deiner Ehre voll,

mit Opfern und mit Danken preisen,

«und alles Volk soll sagen:

Amen!»

7. Arie (Alt)

Halleluja, Stärk und Macht

sei des Allerhöchsten Namen!

8. Choral

Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren

Gott, Vater, Sohn, Heiligem Geist,

der woll in uns vermehren,

was er uns aus Gnaden verheisst,

dass wir ihm fest vertrauen,

gänzlich verlass’n auf ihn,

von Herzen auf ihn bauen,

dass uns’r Herz, Mut und Sinn

ihm tröstlich soll’n anhangen;

drauf singen wir zur Stund:

Amen, wir werden‘s erlangen,

glaub’n wir aus Herzens Grund.

Meinrad Walter

“Between Church and City Hall”

A problematic balancing act between love of God and its political appropriation becomes audible in the text of the cantata “Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir”. But Bach’s music seems to want to take sides – for the heavenly.

In the middle of the concert, which can certainly be understood as a musical ritual, the contemplation of the cantata text leads us on the trail of another ritual, that of the change of council. The words set to music by Bach were part of a political-ecclesiastical celebration in the fair city of Leipzig, celebrated on the Monday after Bartholomew, early in the morning, at seven o’clock in the Nikolaikirche. This reflection takes place on one day and at one hour, as we could already be intoning the first vespers in honour of the Apostle Bartolomew, as tomorrow, 24 August, is his memorial day. So we are well on time.

But we are no longer in the Bach era! And that makes this cantata text unwieldy to my ears. The words pay homage to a pre-democratic view of the world and of humanity. They make me wonder whether the image of God is also infected by this, because perhaps the city makes itself so big as a kind of idol that God has to become all too small. I want to reflect on this a little and neither praise the text rashly nor condemn it. I want to try to understand it.

A big WE celebrates itself with this music. That is why it is a collective text. On the other hand, one word that characterises so many Bach cantatas does not appear here at all: the word “I”. Let’s just think of the most I-containing cantata title in Bach: “Ich, ich, ich – ich hatte viel Bekümmernis in meinem Herzen”. Johann Mattheson rebuked the many Ich with a pointed pen in 1725. But only a few years ago, the singer-songwriter Wolf Biermann rehabilitated that cantata on Swiss television, from poet to poet, so to speak, by referring to his own poem, a protest poem, which begins very similarly: “Ich, ich, ich … Das Kollektiv liegt schief”. And that could be my question: How crooked is the Leipzig collective around 1730 with this cantata? And another side aspect: did Bach’s music perhaps straighten something out?

The norm and its subversion

First of all, the cantata text fulfils its norm. It is biblically inspired and at the same time musically inspiring, full of images and affects that bubble up to the composer as ‘sources of his musical invention’. In addition to the I, however, Jesus is also missing from this cantata, apart from a hint of the Son in the final chorale. The theme is not, as so often, Jesus and I, but: We and God. Or more precisely: we under God’s protection and grace and care.

The very first aria brings out the essentials of the Jewish faith: the praise of God, condensed in the jubilant cry of “Hallelujah” (later supplemented by “Amen”), then the “name” of God, and his “dwelling place” in the temple on Mount Zion, and last but not least God’s rule and activity in history. And it is precisely here that the Christian “us” is introduced poetically-theologically. From those fathers, at that time, the wide arc reaches to ‘us’, and even further: to the ‘seed’. Thus the ‘we anno 1731’ moves into the poetic-theological centre. A Jewish intrinsic value of all this, about which I do not want to be silent today, Trogen 2013, obviously did not enter the poet’s mind at the time. Behind the Christian appropriation, justified as it is, the Jewish-original subjects and places blur, even disappear contourlessly in the background.

The following recitative intensifies all of this – and at the end gets alarmingly into a kind of self-praise: “Where is such a people as we, to whom God is so near and gracious!” This may bring music-critical sentences of the Bible to mind, for example from the mouth of the prophet Amos: “Put away from me the noise of your songs; for I do not like to hear your psaltery!” (Amos 5:23). Or also Psalm 82: “Ye are gods, and all the children of the Most High; but ye shall die, and perish as a tyrant” – this was the sermon text at the last performance of our cantata in 1749.

Legitimisation of the change of council

I now read this cantata text as ‘Variations on a Place’. Variations need a theme. It is called “Zion”, in other ‘council pieces’ also “Jerusalem”, which means the same thing. And at the same time, the place is called “Leipzig”. For Zion becomes the legitimisation of the change of council in Leipzig. Obviously political events, here it is a threshold situation, are dependent on a ritual design that they are hardly able to create themselves. The community borrows rituals from the church, which has specialised in such things since time immemorial. And among these specialists of the ritual in Leipzig are the Thomaskantor Bach and the librettist of this work, whose name is unknown.

But what does the poet do with his subject, the place? The first aria for tenor establishes the place, as it were: Zion is the city of God, where he has his dwelling. One looks back to this, in the direction of one’s own origins. At the same time, a decisive question comes into play: What do we have to do with Zion? For the time being, an answer is only hinted at, a little bit in a cloistered way: The “fathers’ covenant” extends to “our seed”. Continuity and identity, combined with legitimacy, are all extremely important aspects of the change of council. The memory of Jesus’ discontinuous speech and action, which questions old identities and claims a completely new legitimacy, all this would only interfere.

The first recitative “Praise God! we are well!” takes up the drawing of the place and colours it, as it were: the Old Testament city of God, Zion, is now presented as “the city and the palaces”. Justice is demanded – with a biblical quotation from Psalm 85:11 – and peace. The final sentence, however, leaves no doubt that the city of Leipzig is now primarily meant. At the same time, there is again an allusion that is significant: “He causes us to be blessed in all places.” Does this mean: in all our places, whereby the temporal continuity is joined by the spatial certainty that there is nothing ex-territorial, because the Council’s sphere of power does not tolerate any restrictions? Or does God, when he blesses “all places”, not rather also bless all, and everywhere? The text writer cannot and does not want to draw this conclusion. But we may – and not against the cantata, but with it.

Pre-democratic image of the commonwealth

The central soprano aria “Remember us with your love” is a composed prayer. The biblical word that God “remembered” the fathers’ covenant – at that time – is now to become present. The mode of speaking and singing changes: from the indicative to the request “Remember us with your love”. In this way, the librettist creates an extremely coherent dramaturgy: from the biblical promise in the recitative with biblical allusions to the intimate composed prayer of the aria to a vision of fulfilment. And although there is always talk of “we” and “us”, it is now an “I” who sings. A pre-democratic ideal of the community is drawn: on the one hand, “those who guide, protect and lead us” as the hallmark of government; on the other, the obedient, who have to be content with a single line, even though they are in the majority. But that would be a modern-democratic objection, critical indeed, but itself attackable with the argument ‘anachronistic’. More important to me is the inner-biblical criticism from the spirit of the Magnificat: that God will overthrow the mighty from their thrones and exalt the lowly (Luke 1:52). This promise does not come to fruition here. But it does.

Now, with the cantata text, we have stepped from the past, i.e. the origin, through the present to look into the future with the second recitative. “Do not forget…” points hopefully to the future. The city is well aware of how endangered it is, materially and ideally. But now city and country appear in a new light. They are “full of your glory”. I hear this as a liturgical allusion to the chant of the Sanctus: “pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua” – coeli et terra, not only city and country, but “heaven and earth”. The throne vision of the prophet Isaiah (chapter 6) is in the background. And above all, John’s revelation through the affirming formula “Amen, Alleluia”. Thus sounds the heavenly hymn of praise of the 24 elders at God’s throne (Revelation 19:4). It is sung to the councillors of Leipzig, both old and new, three times 12 in all, so that they identify with it and adopt it. Also at the change of councillors in the council house in Leipzig, 24 elders, namely the 12 old and the 12 new councillors, first sit opposite each other and then exchange places after taking the oath of office. This completes the change of councillors.

And we are at the question of who actually sings in each of these text sections. This is no less important than the question of what is sung. However, there are no role names in the libretto. At best, they are written between the lines. In the first chorus, a ‘we’ sings as a community of believers and celebrators. In the tenor aria we hear an ‘I’ from this community, in the recitative probably a representative of the city who knows it well. I imagine him like this: He has put on the chain of office and is filled with civic pride. In general, it seems to me that he has the right answer to all questions. But how different the soprano aria: a childlike prayer, on its knees. The poet divides people into the governing and the obedient. Bach, however, chooses another aspect that connects both groups of people: the miserere nobis, or better here: miserere mei. But why does the basso continuo pause again and again? Perhaps because even the city and its palaces are not sure of their foundations? Now we are entering speculative regions, but that can hardly be avoided in a reflection on Bach. It certainly seems to me that Bach musically overpaints this textual image with another biblical motif, as it were: the shepherd and his sheep. Here, the lost sheep begs for mercy. Do the Leipzig councillors still recognise themselves in this image of seeking and finding? We should not rule it out.

Envelope into the heavenly

In the next movement, the pointedly placed “Amen” surprises us – Bach not only set it to music and interpreted it, but also performed it chorally, which makes it the shortest turba chorus in Bach’s sacred vocal works – but how effective! Here the change occurs, not only into the collective, thank God, but also into the heavenly. For this collective is no longer merely earthly. At least, that’s how I think Bach understood it.

Words from the first aria are heard a second time, and this repetition sets the doxology precisely poetic-musical in motion: “as it was in the beginning (on Mount Zion), so also now and always (here at this and the further changes of council), and then in eternity (before God’s throne), amen.” The city, whose best is at stake (Jeremiah 29:7), is understood as a late reflection, musically as an echo of the old covenantal city – and at the same time as a kind of foretaste, as it were a prelude to the eternal heavenly one, which shines as the new Zion and in which the Canticum novum resounds incessantly, sine fine. This final heightening, in word and sound, is brought about by the final chorale: a kind of “Te Deum laudamus”, as was (and is) typical of political music.

The text of the cantata “Wir danken, dir, Gott, wir danken dir” is as good as it is problematic. When I read it, several lines bounce off me. That, too, is a variant of reflection. That is not my world! Many church cantatas in the annual cycle are much closer to me. When I then hear the words, Bach’s music reconciles me with several aspects. One sentence remains offensive: ” Where is such a people as we, / To whom God is so near and gracious!” Between “We thank you, God, we thank you” (Psalm 75:2) and “I thank you, God, that I am not like other people …” (Luke 18:11) there seems to be a fine line. The biblical option suggested by Jesus in Luke’s Gospel – it is famously called “God, be merciful to me a sinner” – simply comes up short for me in this cantata text.

Reconciling music

But it is precisely with the overly self-assured sentence that Bach’s music reconciles me in the last three bars of Recitative No. 4. Especially important at the very end is the punctuation mark. In two contemporary printed texts and in Bach’s manuscript, it is an exclamation mark – unfortunately. I could still live with a question mark. Incidentally, the tenor in Bach’s performances read neither an exclamation mark nor a question mark, but a full stop, from the pen of Bach’s pupil Johann Ludwig Krebs. Bach, however, composes a question. Yes, he bends the exclamation mark musically into a question mark, so to speak. A kind of Phrygian final turn with a raised third, which at the same time leads into the sphere of affect of the soprano aria. We hear an exclamation of “we”, which is, however, stripped of its harmonic foundation as soon as it sounds. The raised “we” corresponds to a lowered tone at the word “God” (C instead of C-sharp) – musical symbols of raising oneself in the sense of superbia and lowering oneself in the sense of humilitas, even kenosis. The harmony underlines all this. At the very end, Bach lays the foundation for a cadenza in G major, which he deliberately does not bring to completion, but rather turns to B major. This is Bach’s harmony of the question mark.

Today, I can explain and understand the rite of the change of councils and its aesthetic staging, comment on it and criticise it in its idolic tendency. The change of council seems to me to be an endangered fringe of the religious – highly interesting, however, and simply an aspect of Johann Sebastian Bach’s life.

That is one thing, the historical dimension: how it was. The biblical and above all the eschatological aspects, on the other hand, open up possibilities not only of explanation and understanding, but – on this basis of course – of a present-day appropriation. It will always remain extremely personal. There is no better help for it than the second – in Bach’s baroque language – the ‘other’ hearing: a hearing even that does not constitute the text, but nevertheless the sense of the text, just as the interpreters also constitute the musical sense. This listening to the words and to the music is the most important thing.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).