Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid

BWV 003 // For the Second Sunday after Epiphany

(Ah God, how oft a heartfelt grief) for the Second Sunday after Epiphany, for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trombone, oboe d’amore I+II, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Wo der Herr nicht das Haus baut, so arbeiten umsonst, die daran bauen. Wo der Herr nicht die Stadt behütet, so wacht der Wächter umsonst. Es ist umsonst, dass ihr früh aufstehet und hernach lange sitzet und esset euer Brot mit Sorgen; denn seinen Freunden gibt er’s schlafend.

Hat jemand Weissagung, so sei sie dem Glauben gemäss. Hat jemand ein Amt, so warte er des Amts. Lehret jemand, so warte er der Lehre. Ermahnt jemand, so warte er des Ermahnens. Gibt jemand, so gebe er einfältig. Regiert jemand, so sei er sorgfältig. Übt jemand Barmherzigkeit, so tue er’s mit Lust. Die Liebe sei nicht falsch. Hasset das Arge, hanget dem Guten an. Die brüderliche Liebe untereinander sei herzlich. Einer komme dem andern mit Ehrerbietung zuvor. Seid nicht träge in dem, was ihr tun sollt. Seid brünstig im Geiste. Schicket euch in die Zeit. Seid fröhlich in Hoffnung, geduldig in Trübsal, haltet an am Gebet.

Und am dritten Tage ward eine Hochzeit zu Kana in Galiläa; und die Mutter Jesu war da. Jesus aber und seine Jünger wurden auch auf die Hochzeit geladen. Und da es an Wein gebrach, spricht die Mutter Jesu zu ihm: «Sie haben nicht Wein.» Jesus spricht zu ihr: «Weib, was habe ich mit dir zu schaffen? Meine Stunde ist noch nicht gekommen.» Seine Mutter spricht zu den Dienern: «Was er euch sagt, das tut.» Es waren aber allda sechs steinerne Wasserkrüge gesetzt nach der Weise der jüdischen Reinigung, und ging in je einen zwei oder drei Mass. Jesus spricht zu ihnen: «Füllet die Wasserkrüge mit Wasser!» Und sie füllten sie bis oben an. Und er spricht zu ihnen: «Schöpfet nun und bringet’s dem Speisemeister!» Und sie brachten’s. Als aber der Speisemeister kostete den Wein, der Wasser gewesen war, und wusste nicht, woher er kam (die Diener aber wussten’s, die das Wasser geschöpft hatten), ruft der Speisemeister den Bräutigam und spricht zu ihm: «Jedermann gibt zum ersten guten Wein, und wenn sie trunken geworden sind, alsdann den geringern; du hast den guten Wein bisher behalten.» Das ist das erste Zeichen, das Jesus tat, geschehen zu Kana in Galiläa, und offenbarte seine Herrlichkeit. Und seine Jünger glaubten an ihn.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Stephanie Pfeffer, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Maria Weber, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Antonia Frey, Stephan Kahle, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Pfister-Scherer

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Joël Morand, Christian Rathgeber, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Serafin Heusser, Daniel Pérez, Retus Pfister, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Elisabeth Kohler, Olivia Schenkel, Marita Seeger, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Jakob Herzog

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Trombone

Henning Wiegräbe

Oboe d’amore

Katharina Arfken, Clara Espinosa Eucinas

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Christoph Quarch

Recording & editing

Recording date

12/02/2021

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

14 January 1725, Leipzig

Text

Martin Moller (movements 1, 2, 6)

Unknown poet (movements 3–5)

In-depth analysis

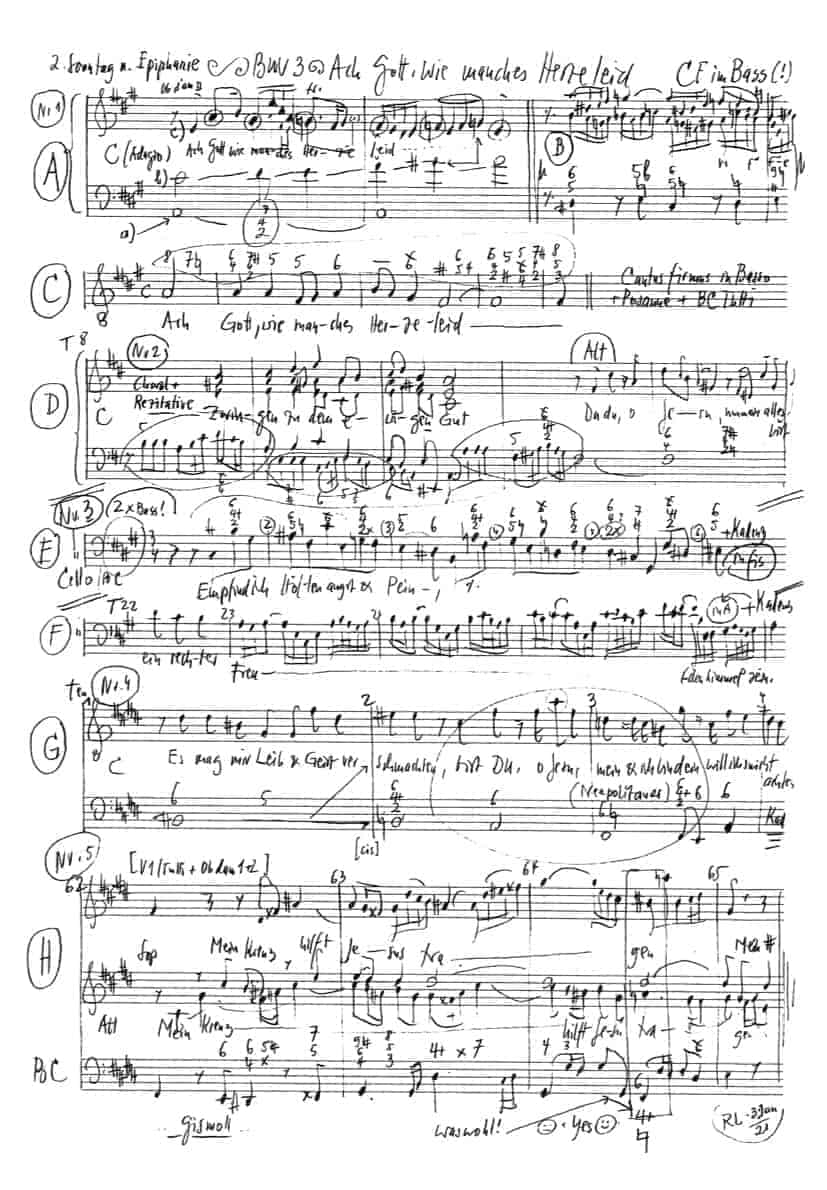

The chorale cantata BWV 3 “Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid” (Ah God, how oft a heartfelt grief) was composed for the Second Sunday after Epiphany in 1725. Its libretto is only loosely related to the Sunday gospel of the Wedding at Cana; instead, the text provides ample scope – only a few weeks after the Christmas presence of the Saviour – to express grief at the renewed distance to Jesus.

In keeping with this mood, the introductory chorus comes across as a solemn adagio that could also serve as an illustration for nightfall after the crucifixion on the cross. Over a bleak pedal point and sparse string writing based on the second line of the chorale melody, two oboes d’amore exchange a gestural motif that is later vocalised in the lamentation of “Ach Gott” (Ah God). Led by the continuo, the inert setting gradually gains a halting momentum and attains heart-breaking poignancy when the vocalists enter over sighing string gestures. The assignment of the cantus firmus to the bass (doubled by a trombone) enhances the dejected mood of the movement, whose stark modulations, harmonic dissonance and gloomily dense line conclusions evoke moments of end-of-days despair. In this setting, the oboes bravely sustain a lament that, although funereal in tone with its accompaniment of sighing string rhythms, is nonetheless warmed throughout by the glowing A major tonality; indeed, with the soprano’s musical journey to the heavens, the conclusion of the movement is not without hope.

The following recitative, too, is dominated by the chorale. Here, the continuo ritornello, which is derived entirely from the hymn melody, introduces a spirited cantional setting that is broken up by self-critical reflections from the four soloists, the last being a long passage by the bass that harks back to the Christmas message while also alluding to the Passion of Christ.

Although the following aria breathes life into the compact chorale gesture, the setting is nonetheless extremely dense and melodically complex in character. Scored for bass and continuo alone, the setting makes for a dark and profound constellation that evokes the “Höllenangst und Pein” (fear of hell and pain) from which the “Freudenhimmel” (heavenly joy) of the heart can emerge only with great difficulty; indeed, although the extended setting highlights the name of Jesus in the middle section, the overall mood of perpetual “Schmerzen” (sorrows) remains. These thoughts are then taken up in the tenor recitative, which emphatically states the soul’s determination to become one with Jesus, to follow his example with no fear of death and the grave, thus allowing, after the bleak C-sharp minor of the aria, a setting in an inwardly radiant E major to prevail.

In the following duet, even the character of the upward leaping fourth is transformed compared to the introductory chorus, and the sighs of humility are succeeded by a trusting determination to overcome all earthly troubles. Nonetheless, the difficulty in escaping the bonds of existential fear and weak faith is rendered palpable through the tight framework consisting of a quasi-ostinato continuo part, an upper instrumental voice in unison and soprano and alto soloists – in the valiant vocal duo, we can almost hear the boy singers of Bach’s elite choir pushing themselves to new heights. In the middle section, knowing that Jesus shares the burden of the cross engenders positive acceptance even of suffering (“Es dient zum Besten allezeit” – It serves me best in every hour), while the syncopated instrumental motif seems to lend an approving nod from on high.

In the form of a compact congregational hymn, the closing chorale expresses the soul’s longing for reunification with the saviour, thus dispelling the desolate mood of the introductory chorus on both a textual and musical level; here, the use of a horn to double the soprano part gently shades the return to the tonality of A major.

Libretto

1. Chor

Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid

begegnet mir zu dieser Zeit!

Der schmale Weg ist trübsalvoll,

den ich zum Himmel wandern soll.

2. Rezitativ und Choral — Sopran, Alt, Tenor, Bass; Chor

Wie schwerlich läßt sich Fleisch und Blut

so nur nach Irdischem und Eitlem trachtet

und weder Gott noch Himmel achtet,

zwingen zu dem ewigen Gut.

Da du, o Jesu, nun mein alles bist,

und doch mein Fleisch so widerspenstig ist,

Wo soll ich mich denn wenden hin?

Das Fleisch ist schwach, doch will der Geist;

so hilf du mir, der du mein Herze weißt.

Zu dir, o Jesu, steht mein Sinn.

Wer deinem Rat und deiner Hülfe traut,

der hat wohl nie auf falschen Grund gebaut.

Da du der ganzen Welt zum Trost gekommen

und unser Fleisch an dich genommen,

so rettet uns dein Sterben

vom endlichen Verderben.

Drum schmecke doch ein gläubiges Gemüte

des Heilands Freundlichkeit und Güte.

3. Arie — Bass

Empfind ich Höllenangst und Pein,

doch muß beständig in dem Herzen

ein rechter Freudenhimmel sein.

Ich darf nur Jesu Namen nennen,

der kann auch unermeßne Schmerzen

als einen leichten Nebel trennen.

4. Rezitativ — Tenor

Es mag mir Leib und Geist verschmachten,

bist du, o Jesu, mein

und ich bin dein,

will ichs nicht achten.

Dein treuer Mund

und dein unendlich Lieben,

das unverändert stets geblieben,

erhält mir noch dein’ ersten Bund,

der meine Brust mit Freudigkeit erfüllet

und auch des Todes Furcht,

des Grabes Schrecken stillet.

Fällt Not und Mangel gleich von allen Seiten ein,

mein Jesus wird mein Schatz und Reichtum sein.

5. Arie — Duett Sopran, Alt

Wenn Sorgen auf mich dringen,

will ich in Freudigkeit

zu meinem Jesu singen.

Mein Kreuz hilft Jesus tragen,

drum will ich gläubig sagen:

Es dient zum besten allezeit.

6. Choral

Erhalt mein Herz im Glauben rein,

so leb und sterb ich dir allein.

Jesu, mein Trost, hör mein Begier,

o mein Heiland, wär ich bei dir.

Christoph Quarch

Ah God, how oft a heartfelt grief…

“Ah God, how oft a heartfelt grief I am encountering at this time!” The first sentence resonates. It speaks of suffering in hard times, or of suffering at a hard time – a time like this, perhaps, that offers ample cause for sorrow and grief. Not only because the Covid pandemic has already claimed many lives, but above all because it reveals how little our Western societies are capable of dealing with such a crisis: how little technology, science and economics enable us to use this crisis as an opportunity for departure; how much we are trapped in conventional ways of thinking and frozen in comfort. “Ah God, how oft a heartfelt grief I am encountering at this time!”, I too am tempted to sigh. I feel a strong resonance with this first movement of our cantata. But only with this one. Why?

The movement is addressed to what it speaks of: to the heart. And that is where it creates resonance. What follows, however, does not reach my heart in any way. It speaks to the head – and the will. It is dominated by words like “should”, “must” or “may”. It is about “forcing” and about “wanting”. It is about a struggle of the subject with itself, about an inner conflict that, following an old language game, exists between “flesh” and “spirit”. Thus, the opening sigh in the second stanza is followed by a completely different theme, which no longer has anything to do with the heartache in this time – which is encountered in this time – but only with what the subject of this cantata observes in himself: with the difficulty of dominating, even “forcing” his own “flesh and blood” – to the point that the soprano laments quoting the Gospel:

The flesh is weak, but the spirit wants.

Instead of singing of the heartache that is encountered at this time, the cantata henceforth engages in self-referential reflections of the believing subject. Although this ends the resonance of the heart, it makes the cantata interesting for the philosopher. In what way?

The cantata is interesting because it provides insight into the genealogy of our thinking. What does that mean? Well, the way we think is not natural. It is the product of an intricate history, as a result of which a conception of man became established, according to which we now live, work, do business, organise our world and try in vain to master a global pandemic. This image of man has been called Homo Faber or Homo Oeconomicus – depending on whether one focuses on his obsession with technology or his egocentricity. Its most recent manifestation, if we follow the Israeli bestselling author Yuval Noah Harari, is Homo Deus, who pursues only one goal: to conquer death with the help of the most advanced technology.

But Homo Deus, Homo Oeconomicus and Homo Faber only became possible because, in the wake of the Reformation, the idea prevailed that man is the being who can will by virtue of his mind – and whose will to believe will decide whether or not there will be salvation for him from “final doom”. Our cantata now transports us, as it were, to the childhood of this image of man. From afar, there are still echoes of medieval Christ mysticism, but in the middle section – especially in the third movement – the self-reflection of a subject dominates, which on the one hand constitutes itself in the triangle of want, should and must, and on the other hand in relation to its flesh.

The focus on death is characteristic of the self-understanding that is formed here in statu nascendi, first in the Reformation and then in modern times. Martin Luther had let the faithful know in a Wittenberg Lenten sermon:

We are all called to death, and no one will die for the other, but each in his own person will struggle with death for himself.

Death thus became a memento mori, calling the believer to responsibility for his own life and salvation. It is now up to the believing subject to conquer “the fear and torment of hell”, which “may only call Jesus’ name”, in order to transform the terrors of the heart into a “heaven of joy”, or to “calm the fear of death, the terror of the grave” and “fill the breast with joy”. Therefore, it is only logical when the believing subject confesses in the fifth sentence:

When sorrows press upon me,

I will sing with joy

Singing to my Jesus.

My cross Jesus helps to carry,

Therefore I will say with faith:

It serves for the best always

Twice the subject confesses that it wants. It wants “joyful heaven” and “joyfulness”, it wants consolation, it wants salvation. And it relies entirely on a theological theory that demands this will:

Since thou hast come to the consolation of the whole world,

And took our flesh unto thee,

Your death saves us

From finite ruin.

As a finite subject, the believer sees it as his duty to expect his consolation and salvation from Jesus alone – for he is promised that both will be granted to him, provided he is willing to rely on this salvation. And in fact, the hoped-for comfort in his “fear and torment of hell” grows out of his will for salvation through Jesus. But all this is a purely cognitive operation that the believing subject carries out within himself. It finds comfort and salvation in itself: in its will to believe.

This self-referentiality is the unique characteristic of the new image of man that developed under the influence of the reformers in the 16th and 17th centuries and which resounds through our cantata. It proclaims man to be a willing subject who, by virtue of his will to believe, can assert himself against two opponents: against “need and want”, which he strives to transform into “wealth”, and against “death’s fear” and “grave’s terror”, which he must turn into a “heaven of joy”. In its way, however, are the impulses and inclinations of the “flesh”, which cannot be “forced” so easily. And that causes this subject “heartfelt grief”.

But is this also the “heartfelt grief” of which the first line of our cantata speaks? Is it the heartfelt grief that is encountered in this time? Is it a felt suffering that arises from the heart’s attachment to the world – from empathy with “this time” – this concrete time? Is it not rather a home-made suffering that grows out of the self-centredness of a subject concerned with its personal advantage – or its salvation and comfort; the suffering of a subject that wants to rely on its Saviour – and cannot do so as it would like?

The self-concerned modern subject that expresses itself here finds neither suffering nor consolation in its heart, but only in its head. And that is why my resonance of the heart ends after the second verse of this cantata. Until then, it touches my heart. But what comes after that is theory or theology. And unfortunately bad theology, because it has produced an image of man and a world that today cause me “heartfelt grief” – real heartache of despair at the self-referentiality of man. Especially at this time, especially in a pandemic that should actually encourage us to awaken from the trance of our self-reference and to develop a new sense of belonging, community and connectedness: with our fellow human beings and with nature.

Instead, we behave – in only a slightly modified way – much like the subject of our cantata. We are afraid of need and want, driven by the fear of death and the terror of the grave. We rely on our will, which relies on promises given to us and which we want to trust, even if we don’t understand them, for example: The (un)holy trinity of economy, science and technology will save us. Or: With the help of your will, your optimism or your positive psychology, you can transform your fear of hell into a heaven of joy – even if you have to “force” the sadness, the tiredness, the dejection, the weakness of your body to do so. If the subject of our cantata sees himself as the architect of his faith and thus of his salvation, the subject of the present sees himself as the architect of his happiness with the help of technology, science and economy.

Structurally, nothing has changed in our self-image since 1725. Structurally, we are still trapped in self-reference and constantly revolve around ourselves. And nothing has improved because we no longer hope for the help of Jesus, but for the help of … experts.

The whole thing is tragic because our self-referentiality prevents us from taking the path that could really save us: the path with which our cantata begins: “Ah God, how oft a heartfelt grief I am encountering at this time!” Yes, I am encountering suffering at this time. It is not the product of self-centred concern for my well-being, but of the encounter with the world that touches my heart: with the despondent people who have lost their perspective of meaning in the pandemic or with the young people who see themselves cheated of their youth. But it is not only them who cause me heartache, but also the empathy-free politicians who govern us, or the saturated beneficiaries of the crisis.

Anyone who goes through the world mindfully and doesn’t think that there must always be a “right heaven of joy” in his heart will feel plenty of “heartfelt grief” – and the “heartfelt grief” will tie him back to what he is not himself. It will free him from self-reference and make him aware of his connection with other people and nature. It will break the sinister image of man of modern times, which has sprung from a sinister Reformation theology. Heartache can become the source of a new reconnection – religio in Latin – to the being of this world, the source of a new image of man that has its centre in the heart and not in the will and that interprets man as a relational being who does not find fulfilment in self-reference but in the encounter with the other. Martin Bu-ber, the great Jewish religious philosopher, once said:

All real life is encounter.

That is probably true. Even – or even especially – when the encounter causes heartache. “Ah God, how oft a heartfelt grief I am encountering at this time!” – And that is good.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).