O ewiges Feuer, o Ursprung der Liebe

BWV 034 // For Pentecost (Whitsunday)

(O fire everlasting, O fountain of loving) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpets I–III, timpani, flauto traverso I+II, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings, organ and harpsichord.

The Pentecost cantata “O ewiges Feuer, o Ursprung der Liebe” (O fire everlasting, o fountain of loving) BWV 34, is particularly concise in construction despite its magnificent high-day sound. Its five movement form (unusual for a Leipzig church cantata) with only one aria and no closing chorale suggests it may well be a parody work – and, in fact, the first, third and fifth movements do originate from a wedding cantata of the same name (BWV 34a) that survives only in part today.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Leonie Gloor, Guro Hjemli, Jennifer Rudin, Noëmi Tran Rediger

Alto

Alexandra Rawohl, Olivia Heiniger, Francisca Näf, Damaris Nussbaumer, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Nicolas Savoy, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Chasper Mani, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Plamena Nikitassova, Sylvia Gmür, Sabine Hochstrasser, Fanny Pestalozzi, Olivia Schenkel, Fanny Tschanz, Livia Wiersich

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof, Joanna Bilger

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Luise Baumgartl, Martin Stadler

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Klaus Pfeiffer

Transverse flute

Maria Mittermayr, Renate Sudhaus

Timpani

Martin Homann

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Oren Kirschenbaum

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Arthur Godel

Recording & editing

Recording date

05/29/2009

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Poet unknown

First performance

First Day of Pentecost,

probably in May 1746 or 1747

In-depth analysis

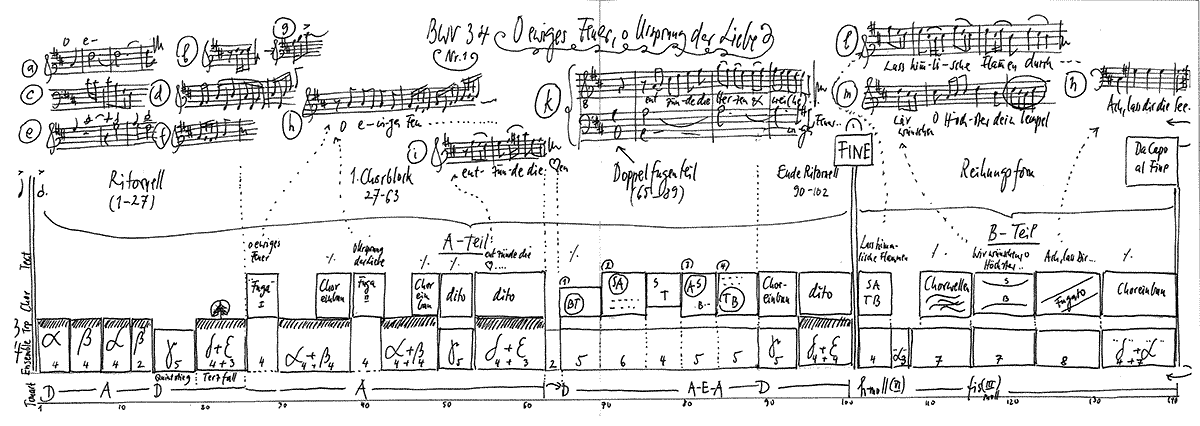

The opening chorus is conceived as a three-choir orchestral concerto (trumpets and timpani, oboes, and strings) in da capo form. In particular, the partially aria-like, partially broad contrapuntal choir section with its euphonic declamation demonstrates exceptional maturity in its craftsmanship. Even the middle section of this fragmented movement, which begins with an elegant vocal duet, features an expressive fugue (“Ah, let our souls please you in faith”).

After a brief recitative, an alto aria follows in which the original text of “ye chosen of the shepherd” was amended to “ye, the chosen spirits” in the parody work, without giving rise to changes in the pastoral music. Two transverse flutes, doubled an octave lower by muted violins, evoke a peaceful mood over the gentle long-tones of the bass and viola, while the long stretches of syncopated melody lend the movement a modern touch. The brief recitative no. 4 forms a transitional movement, building up to an oratorical colon that culminates in the massive tutti choral proclamation “Peace be over Israel” and a final movement of light-hearted rejoicing. In this last section, a sweeping figure sends the soprano soaring over one and a half octaves up to a second ledger-line “A”. This slide figure, originally set for the Wedding Cantata to the text “Haste unto that holy stairway”, is equally effective as text painting for “Thank the lofty hands of wonder” and deftly demonstrates the skill of the baroque librettists and the efficiency of the oft-criticised parody technique.

Considering its composition date of the mid 1740s and its striking style, one is tempted to think Bach was experimenting with the gallant style of his sons and students. If, however, we remember that the original composition was written in 1726, it becomes apparent that Bach had long mastered this popular style and was, in a sense, ahead of his time. It is certainly the case that Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was able to perform his father’s work decades later in Halle with no loss of face whatsoever.

Libretto

1. Chor

O ewiges Feuer, o Ursprung der Liebe,

entzünde die Herzen und weihe sie ein.

Lass himmlische Flammen durchdringen

und wallen,

wir wünschen, o Höchster, dein Tempel

zu sein,

ach, lass dir die Seelen im Glauben

gefallen.

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Herr, unsre Herzen halten dir

dein Wort der Wahrheit für:

du willst bei Menschen gerne sein,

drum sei das Herze dein;

Herr, ziehe gnädig ein.

Ein solch erwähltes Heiligtum

hat selbst den grössten Ruhm.

3. Arie (Alt)

Wohl euch, ihr auserwählten Seelen,

Die Gott zur Wohnung ausersehn.

Wer kann ein grösser Heil erwählen?

Wer kann des Segens Menge zählen?

Und dieses ist vom Herrn geschehn.

4. Rezitativ (Bass)

Erwählt sich Gott die heilgen Hütten,

die er mit Heil bewohnt,

so muss er auch den Segen auf sie schütten,

so wird der Sitz des Heiligtums belohnt.

Der Herr ruft über sein geweihtes Haus

das Wort des Segens aus:

5. Chor

Friede über Israel.

Dankt den höchsten Wunderhänden,

dankt, Gott hat an euch gedacht.

Ja, sein Segen wirkt mit Macht,

Friede über Israel,

Friede über euch zu senden.

Arthur Godel

“From the fire of Bach’s music”.

Three core words with a great aura characterise the text of the Pentecost cantata “O eternal fire, O origin of love”. In the following reflection, they appear as keys to understanding Bach’s music.

Eternal fire

“O eternal fire, o origin of love” – the striking opening verse of the cantata suggests that we reflect on the fire of Bach’s music. About the energy that emanates from it and its effect on us.

Where does this musical fire come from? Where does the inspiration come from? Is it the roaring of the Spirit, descending on the disciples in tongues of fire, as the Bible describes the miracle of Pentecost? The fire of the Spirit enabled the disciples to speak in many languages, why not also in the language for the actually unspeakable, in the language of music?

That inspiration is of divine origin is a myth that has accompanied man’s artistic activity from the beginning, and in Bach’s time the conviction was still unbroken: Everything comes from God and goes to God. Bach signed many of his works with “Soli Deo Gloria” (In honour of God alone).

When asked about the origin of his ideas, however, the Baroque composer initially gave a much more sober answer. He sees himself as a craftsman in the service of a commission, as an artifex, not unlike the stonemasons and carpenters who build a house or a church. He does not see himself as a creator but as a kind of re-creator, he represents with his tools what God has placed as a possibility in the world and in music. It was not until a generation after Bach that the artist placed himself, the expression of his own feelings, at the centre, attributed godlike creative power to himself and proudly exclaimed: “Did you not complete all this yourself, holy glowing heart?” This exclamation of the young Goethe would never have crossed Bach’s lips. Goethe compares himself as an artist to Prometheus, the Titan who stole fire from the gods to bring it to mankind.

Music, ars musica, according to the Baroque conception and in accordance with a long tradition, is a craft and as such can be taught and learned. Unlike today, music lessons have always included inventing music, the inventio. When Bach’s first son, Wilhelm Friedemann, was ten years old and was taught to play the piano, his father composed two-part pieces for him, so-called inventions, which exemplified the process of musical invention. Friedemann could watch the invention of a musical theme and its artful elaboration. Johann Sebastian himself learned to compose in a similar way. Bach noted about these two- and three-part inventions that they were a “sincere instruction, with which a clear way is shown to lovers of the clavière, but especially to those eager to learn, not only to learn to play purely with two voices, but also (…) not only to get good inventiones, but also to carry them out well. The Inventions are thus at the same time a textbook of piano playing and a textbook of musical invention (inventio) and elaboration (elaboratio).

But how does the inventio come about, the finding of a sequence of notes that can then be “well executed”? In Bach’s time, every music student learned rational finding techniques as they had been developed by the ancient orators, creativity techniques that are in no way inferior to those taught today.

For a vocal composition, for example, it was recommended to first look for the meaningful words in the text and then translate them musically, such as “fire”, “love” and “peace” in the example of our cantata. The imagery of the words, the flickering of the flames, is to be depicted in music, the meaning – Holy Spirit – represented and the affect – enthusiasm – portrayed.

The invention of the musical theme is one thing, but its elaboration into a complete movement is another, particularly demanding thing. Johann Sebastian Bach took this elaboration, the elaboratio, to a complex, musical context of meaning as far as hardly any musician before or after him. He knew that he was an exceptional artist. In his musical legacy, he set down in exemplary fashion and with his own systematic approach what was possible in terms of contrapuntal thinking, the ars combinatoria, for example in the “Art of the Fugue” and the “Musical Offering”.

The concept of inspiration, central to music after Bach, is only treated as an exceptional case in the textbooks of the Baroque; the musical craftsman could not and did not want to base his métier on the unpredictable favour of inspiration. He needed a solid, reliable basis for his commissions, which were usually bound to short deadlines.

Even the great music theorists of the Baroque era were aware that there is a degree of mastery that is not accessible to everyone. They recognised the cause in talent, the naturalia, as they called it. That someone like Bach, whose family and ancestors numbered over 100 musicians, was genetically favoured is obvious. Is the fire of Bach’s music the result of masterful craftsmanship and lucky genes? Do we have a better explanation today? In the age of creativity research and neurobiology, does it really help us to talk about a neuron storm? What kind of energy is discharged in the head during the thunderstorm of the creative act? We do not want to be satisfied with biochemical explanations. There remains an unsolved residue, where mastery points beyond itself. where explanations are lacking, images set in. The believer speaks of divine power, others speak of cosmic energy. That we need this inexplicable proves our longing for it. Artistic activity from the beginning, from the cave paintings of the Stone Age until today, is connected to this inexplicable. Does this fire burn eternally? “Eternal” – Bach underlines the word several times in His setting with a long held tone. “Eternal”, a big word, a “thunder word”, as it is called in another cantata. In the context of music, it is reminiscent of the Indian myth of the origin of the world, Nada Brahma, according to which the world was created from a sound. Music would thus be the making audible of cosmic power, the vibration of matter and spirit. This is not so far from the baroque idea that earthly music is an image of heavenly music, that in its order and harmony it imitates the eternal order and harmony. In this sense, there would be music as long as there is a concept of heaven, as long as there is a longing for paradise.

Another Pentecost cantata speaks of the “wind of paradise”. When it comes to paradise, music has always occupied an exceptional position, not least because it speaks in its own, conceptless language. Wittgenstein’s sentence “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” could be modified in view of the special expressiveness of music to: “what one cannot speak about, one must sing about.” The literary and linguistic scholar George Steiner calls music “that alluring medium of revealed intuitions beyond words”.

Origin of love

True to the advice of ancient rhetoricians and the approach of a Baroque composer, my thoughts on Bach’s music and its effect so far have started from core words in the cantata text, from the first verse: “fire, origin of love”. but what do we do with the big word “love”?

One verse in this cantata text touches me particularly: “Lord, you want to be with people gladly.” For once, it is not the punishing and avenging God who is addressed here, but the God of affection and love. Not least because of this message, Bach’s nine Pentecost cantatas became promises of happiness and songs of praise for love. However, the Pentecost cantata “O eternal fire, O origin of love” has to do with love in an even more earthly sense. It was originally a wedding cantata. In the original wedding cantata, the affection of the young couple was at the centre. In the altar piece that Bach takes on, this intimacy, this going together, is recreated by two closely related melodies, two souls mirroring each other, so to speak. There is something very intimate about this music, it enlivens our own capacity for love within us.

Pentecost was one of the most strenuous church festivals for a cantor; three new cantatas had to be prepared and performed in the various churches of Leipzig. So it made sense to go back to an earlier work. The core words of the Pentecost reading – “fire” and “love” – reminded Bach of a wedding cantata he had composed 15 years earlier. He needed to make only a few textual adjustments and he had a new cantata for Pentecost. The new version was given a brilliant instrumental sheen: with three trumpets, two oboes and two flutes, the instruments were at hand through which the Pentecostal wind could blow, “air from another planet”, to quote a word by Stefan George.

Bach gave a handwritten score of this cantata to his son Friedemann, who had shortly before become church musician in Halle (incidentally Handel’s birthplace). He was thus able to present, in addition to his own works, an extremely splendid work by his father. This, too, is a testimony to the affection between father and son.

Let us go one step further in our allegorical-musical interpretations of the core word love. Affection also means to relate. According to Bach’s understanding, this begins with the invention of a melodic line, the sequence of notes that follow an inner logic, and continues in the complex interplay of a multitude of voices, in polyphony. Bach’s sons told Johann Niklaus Forkel, the first Bach biographer, how Bach’s composition lessons went: Bach “always paid attention both to the coherence of each individual voice on its own and to its relationship to the voices connected to it and running parallel to it. (…) Each tone had to have its relationship to a preceding one; if one appeared which could not be seen where it came from or where it wanted to go, it was dismissed as a suspect without decency”. This refers not only to the inner relationship of the voices, but also to the strict laws that a polyphonic movement had to follow. But where is the artistic freedom, the room for imagination?

Bach contrasts the strict musical order with a maximum of freedom. We see him before us, a man who radiates strength and courage – who knows how to defend his position as a church musician and artist, a thinker who recognises contradiction as necessary. Forkel tells us that Bach allowed his pupils every freedom in composition, “only nothing had to occur that could be detrimental to the musical euphony or the completely correct, unambiguous representation of the inner meaning”.

In his music, Bach creates a great arc of tension between opposing poles, between freedom and law, expression and thought, complex combinatory art and dramatic directness. As a synthesis thinker, he combines opposites, opera and cantata, Italian and German style, French and German style. He succeeds in inventing expressive music even for weak and sanctimonious cantata texts. He is both a perfector and an innovator, harking back to Palestrina in music history and pointing ahead to Schoenberg and Webern by going to the limits of tonality. He thinks the possibilities of musical language to their limits – and beyond. The opposites are not cheaply reconciled, they find themselves in a tense balance, a state we could also call peace.

Peace

Like a great imperative, which could also be understood as a cry of distress, the chorus in our cantata cries out “Peace on Israel”. When Bach is talking about peace, he is not pretending to be a simple-minded, harmonious peace, he is not celebrating “peace politeness”. Bach knew too well about the opposing forces: “Let Satan rage, rage, rage”, it says in a cantata text, or there is talk of the “sharp claws of the enemy”. Bach also knew everyday discord only too well. In what is probably his most personal surviving document, a letter to his school friend Georg Erdmann, he writes in 1730 of the “whimsical and to music little devoted authorities”, alluding to his dispute with the Leipzig city council and an Amusian rector of the Thomasschule. The same letter also says that he lives “in constant annoyance, envy and persecution”, harsh words for Bach, who otherwise expressed himself rather soberly and formally.

Born into a politically relatively pacified time, Bach had to experience that the music-loving Prussian King Frederick II, to whom he paid his respects, improvised and played music, brought about the Silesian War. Frederick could not only play the flute, but also rattle his sabre. Bach knew as well as we do: Lasting peace is a utopia, an indispensable one, however, a great pipe dream, perhaps even a mirage.

Great music can make the idea of a paradise of outer and inner peace tangible for the duration of a performance; that is the strength and irresistible magic of music, Bach’s in particular. It speaks to us, even detached from the theology of its time; it has its own theology and its own redemption.

When we speak of peace and reconciliation, we call conversation the royal road to it. Bach’s music opens up the conversation with his listeners, it talks to us. This art, so trained in rhetoric, wants to address us, delight us and stir us up – and in its inner structure, the tense harmony of its voices, it recreates a conversation marked by mutual respect and affection.

“He saw his musical voices” – Forkel reports – “as it were as persons conversing with each other like a closed society. If there were three of them, each could remain silent at times and listen to the others until she in turn had something useful to say.”

Talking at the right moment and listening at the right moment – that too is a form of affection. So let us return to the fire of Bach’s music and listen to the cantata a second time.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).