Geist und Seele wird verwirret

BWV 035 // For the Twelfth Sunday after Trinity

(Soul with spirit is bewildered) for alto, oboe I+II, oboe da caccia, bassoon, organo obbligato, strings and continuo.

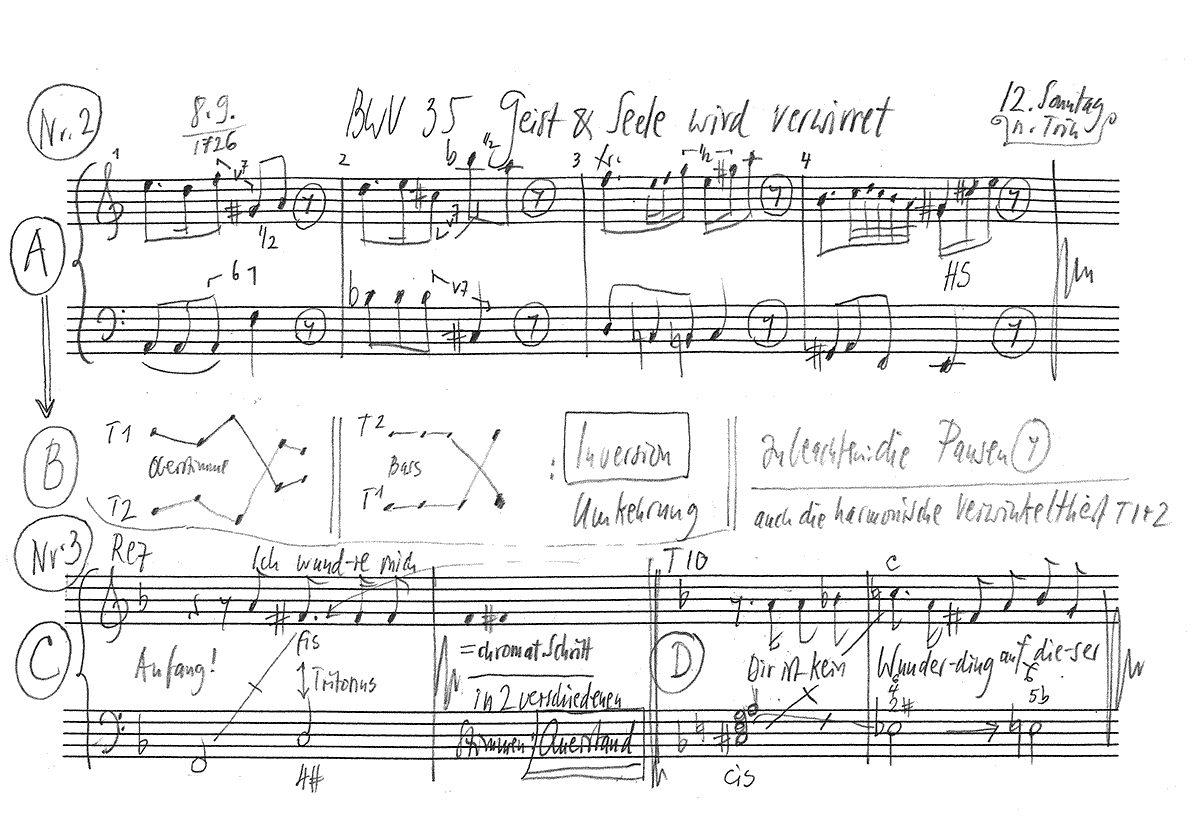

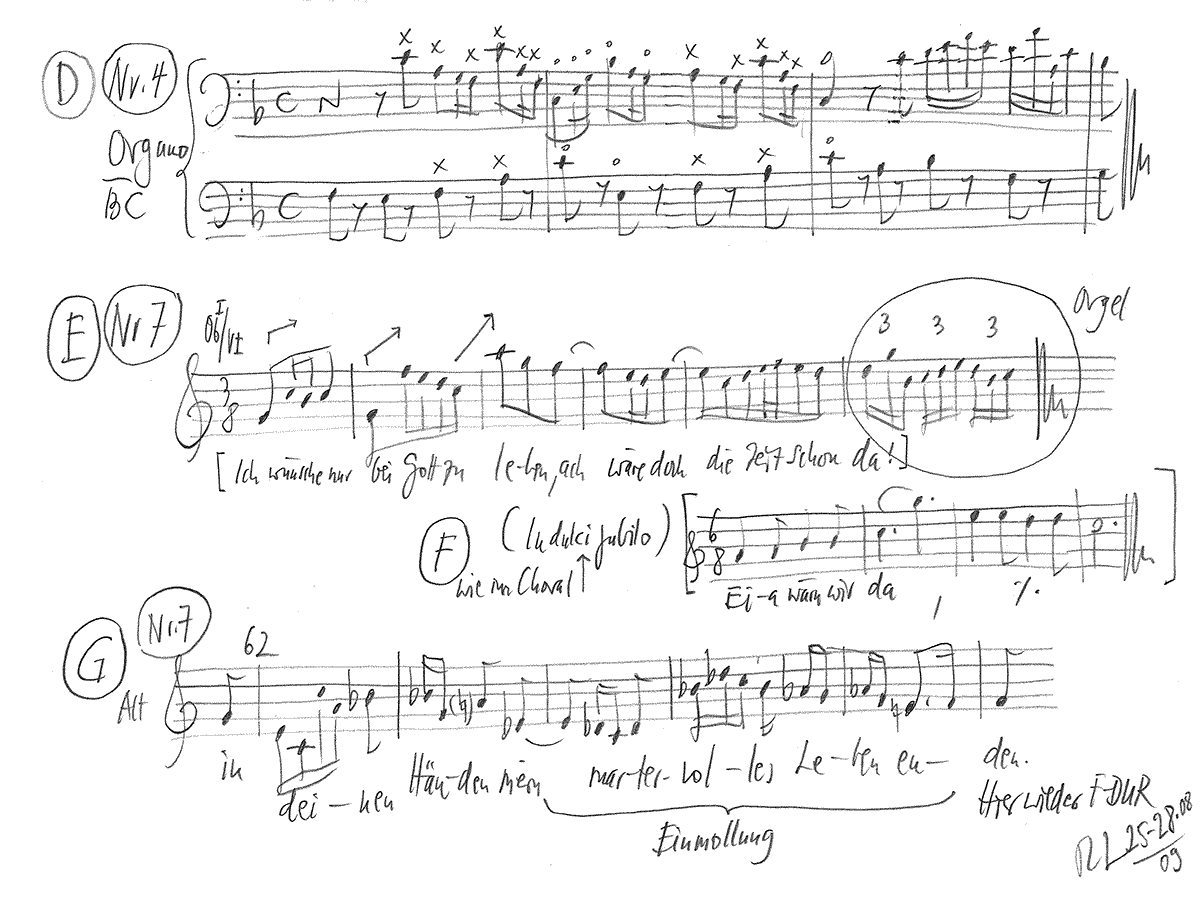

Bach’s alto cantata “Geist und Seele wird verwirret” (Soul with spirit is bewildered) BWV 35, composed for the Twelfth Sunday after Trinity, belongs to Bach’s most unusual sacred works. Composed to a libretto by the Darmstadt court librarian Georg Christian Lehms, it is one of Bach’s few solo cantatas. The lack of a choir is nonetheless magnificently compensated by the orchestration of strings and three oboes. More noteworthy, however, is that Bach uses the organ as a virtuosic solo instrument not only in the opening sinfonia, but in almost every movement. It has long been assumed that at least the two purely instrumental movements (and possibly the first aria of the cantata) were based upon a solo concerto – probably intended for oboe – that remains lost today. A nine-bar fragment in Bach’s hand of the same opening movement for harpsichord, oboe and strings (BWV 1059) is seen as further evidence of a lost concerto.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Alto

Claude Eichenberger

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi, Christine Baumann, Sabine Hochstrasser, Olivia Schenkel, Livia Wiersich

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Xiao Ma

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Thomas Meraner

Oboe da caccia

Luise Baumgartl

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organo Obbligato

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Prof. Dr. Ulrike Landfester

Recording & editing

Recording date

08/28/2009

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Georg Christian Lehms (1684–1717)

First performance

8 September 1726

In-depth analysis

While the introductory D minor concerto of the cantata is powerful and serious in design, the sinfonia in the middle of the work is somewhat Vivaldian in character on account of its repetitive binary form, strict eight-bar sections and its spirited and zestful character. The work’s first aria features a siciliano-like ritornello that is strongly reminiscent of the middle movements of Bach concertos, and the “bewilderment” treated in the libretto is manifested here by the irregular pauses in the anchoring continuo part.

While the preacher for that Sunday’s sermon probably had little difficulty in describing the miracle of the healing of the deaf and dumb (Mark 7, 31–37), Lehm’s rather wilful interpretation of the bible passage did not simplify matters for the composer. The verbose text comes across as somewhat contrived; Bach was evidently inspired to compose a capricious and at times highly elaborate movement, although he refrained from employing the full sound and power of the organ. Instead, the organ’s ornate figures create an atmosphere of intellectual tension and extreme artistry – as if the soul, overwhelmed and rendered “deaf and dumb” by the godly miracle, sought refuge in the mechanical execution of external events. Aside from its role in the concerto movements and recitative accompaniment, Bach succeeds in finding fresh ways of featuring the organ in the three arias. After the highly contrasting use of alto and organ in the first aria (movement 2), the second aria (movement 4) is a lively trio of voice, continuo and the right hand of the organ. In the closing aria, the organ part is autonomous in character, but skilfully integrated into the already dense harmonic structure of the solo alto and full orchestra – a demanding but successful composition. In this movement, the organ’s virtuosic triplet figures, already admirable enough in themselves, also effectively conjure up the spirit of the “glad hallelujah” with which the libretto of the cantata, a work that oscillates between joy in creation and contempt for the world, closes.

Libretto

Prima Parte

1. Concerto

2. Arie (Alt)

Geist und Seele wird verwirret,

wenn sie dich, mein Gott, betracht’.

Denn die Wunder, so sie kennet

und das Volk mit Jauchzen nennet,

hat sie taub und stumm gemacht.

3. Rezitativ (Alt)

Ich wundre mich;

denn alles, was man sieht,

muss uns Verwundrung geben.

Betracht ich dich,

du teurer Gottessohn,

so flieht

Vernunft und auch Verstand davon.

Du machst es eben,

dass sonst ein Wunderwerk von dir was Schlechtes ist.

Du bist

dem Namen, Tun und Amte nach

erst wunderreich;

dir ist kein Wunderding auf dieser Erde gleich.

Den Tauben gibst du das Gehör,

den Stummen ihre Sprache wieder,

ja, was noch mehr,

du öffnest auf ein Wort die blinden Augenlider.

Dies, dies sind Wunderwerke,

und ihre Stärke

ist auch der Engel Chor nicht mächtig auszusprechen.

4. Arie (Alt)

Gott hat alles wohlgemacht.

Seine Liebe, seine Treu

wird uns alle Tage neu.

Wenn uns Angst und Kummer drücket,

hat er reichen Trost geschicket,

weil er täglich für uns wacht:

Gott hat alles wohlgemacht!

Seconda Parte

5. Sinfonia

6. Rezitativ (Alt)

Ach, starker Gott, lass mich

doch dieses stets bedenken,

so kann ich dich

vergnügt in meine Seele senken.

Lass mir dein süsses Hephata

das ganz verstockte Herz erweichen;

ach! lege nur den Gnadenfinger in die Ohren,

sonst bin ich gleich verloren.

Rühr auch das Zungenband

mit deiner starken Hand,

damit ich diese Wunderzeichen

in heilger Andacht preise

und mich als Kind und Erb erweise.

7. Arie (Alt)

Ich wünsche nur, bei Gott zu leben.

Ach! wäre doch die Zeit schon da,

ein fröhliches Halleluja

mit allen Engeln anzuheben!

Mein liebster Jesu, löse doch

das jammerreiche Schmerzensjoch

und lass mich bald in deinen Händen

mein martervolles Leben enden!

Ulrike Landfester

“He who has ears to hear, let him hear: Bach’s Poetics of Wonder”.

Thoughts on the conditions of the emergence of secular art.

Mind and soul are confused, reason and also understanding flee away, everything experienced so far disappears into the grey of meaninglessness, and suddenly we have the feeling of having been deaf, dumb and blind until now – we have all experienced such moments. They are moments in which we are allowed to experience something that perhaps does not directly affect us ourselves in its causes and effects, but which touches us deeply, so deeply that for this moment all our senses lose their usual hold on reality.

The text of the cantata “Geist und Seele wird verwirret” tells us about such a moment, about Jesus’ healing of the deaf-mute, as Mark described it in his Gospel – although strictly speaking, the text does not tell us about a moment, but about the essence of such moments, namely about the essence of the miracle that confuses mind and soul.

If we look at the Gospel of Mark as a whole, we get the impression that this concentration on the essence of the miracle was something like its programme. Biblical scholars have repeatedly stated that this oldest of the four Gospels is the least systematically structured – and perhaps this is not because Mark did not remember exactly what happened; perhaps it has more to do with the fact that Mark understood the task of evangelical witnessing as a task to write the story of Jesus as one that, instead of following the logic of a historical-chronical account, rather unfolded an entire poetics of the miracle.

The Christian religion has systematically placed the poetics of miracles at the centre of its transmission of faith like no other of the great world religions. Already in the Old Testament, the miracles that God performs on man are in the service of a deixis addressed to the emerging community of faith, a gesture of showing. This means that God shows man his power in his miracles and at the same time gives him instructions as to how God-fearing man should behave, how he should build up his social structures and what form he should give to religious worship. While these miracles in the stories of the Old Testament usually fulfil a very specific function – for example, the establishment of the Law, for which Moses receives the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai – the miracles reported in the Gospels are largely free of such functional ties – apart from the one thing on which all four evangelists, despite their different emphases, are in complete agreement: The miracles that Jesus does are to be understood as signs in which the proclamation of the Christian faith becomes capable of being handed down far beyond the moment of revelation itself.

This idea itself has a very pragmatic basis: in a time in which hardly anyone of those who met Jesus can write and read, the miracle in its specialness, which transcends the bonds of the “torture-full life”, remains in memory, is retold and thus secures the continuity of the proclamation of faith even beyond the limits of the elitist medium of writing. In this sense, Jesus’ word sermons take up much less space in Mark than the stories in which Jesus heals the possessed and the feverish, the lepers and the paralysed and, of course, the deaf-mute of our cantata – with one significant exception, however: Jesus’ great parable speech in the fourth chapter of Mark’s Gospel. Here Jesus explains the parable of the sower, whose seeds, when they fall on good soil, bear fruit “sixtyfold and a hundredfold”, the parable-like nature of the miracles he worked (Mark 4:8). Here we also find the famous word: “He who has ears to hear, let him hear” (Mark 4:8) – and this does not simply mean the organ ear, but the inner ear, the willingness to let the miracle come to them as an experience; for some, Jesus continues, do not have this inner ear, and for them it applies: they should “see but not recognise / they should hear but not understand / lest they be converted and forgiven” (Mark 4:12). In other words, those who do not let a miracle like the healing of a deaf-mute open their inner ear are the real deaf-mutes.

The poetics of the miracle is thus unfolded in a highly complex way in the Gospel of Mark, to the point of becoming a whole metaphorology. Our cantata, however, increases this complexity even further by adding a third to the two types of deaf-muteness and its healing that Mark tells of. First, of course, there is physical deaf-muteness, and it is surely no coincidence that the cantata “Geist und Seele wird verwirret” has chosen from the whole wealth of disabilities healed by Jesus according to Mark the one that for Bach, who lived from and with music, and Georg Christian Lehms, who lived from and with speech – the author of its text – may have been the most terrible of all afflictions that could befall man under the “wailing yoke of pain” of his earthly existence. Secondly, there is the metaphorical deaf-muteness of the one who does not recognise the “miraculous works” of God. And thirdly, there is the meta-metaphorical deaf-muteness, so to speak, of those who possibly cannot recognise the direct origin of art from the evangelical poetics of miracles: The I who speaks in the second recitative of our cantata is the double figure of the two creators of our cantata, the poet, for whom God has loosened the “string of tongues” to linguistically represent his “miraculous signs”, and the composer, who translates the poet’s words into the “holy devotion” of the cantata music.

At first glance, it may seem a little peculiar that our cantata celebrates its artistic beauty as a gift of grace bestowed by the “strong hand” of God, and thus celebrates itself as a miracle, and thus claims for its creator to be the “child and heir” of Jesus’ sign-like work. For two reasons, however, this claim is quite justified: On the one hand, it was the task of the cantata to interpret to its listeners the Bible word read in the service, whereby the music took on the task of complementing the biblical scripture by evoking the former auratic presence of Christ in a form that was itself auratic and directly linked to the momentary presence of the performance situation, i.e. to create a moment of experience in which the miracle, as it were, once again took on direct life.

On the other hand, we must not forget that the poetics of the miracle, as the Gospels have unfolded it, is one of the most important and perhaps even the most important founding figure of the art of our Christian occidental culture par excellence. Today, after two centuries of ever increasing secularisation of this art, we know little of the roots that link it to its religious sources. But at the time Bach composed the cantata, in the early 18th century, it was just on the threshold of this secularisation. What we see in the cantata in terms of artistic self-reflection is therefore, on the one hand, still directly based on the principle of proclamation, in the name of which, since late Christian antiquity, every production of beautiful art has seen itself as a revelatory realisation of divine power. On the other hand, the self-confidence with which Bach refers to the artistic character of his creation also foreshadows the revaluation of the creative individual, which in the genius aesthetics of the late Enlightenment that began a few decades later would establish the concept of authorship of modernity and thus emancipate this individual in the name of purpose-free artistic autonomy from the direct divine commitment of his actions – at least in theory.

In practice, the fine arts themselves by no means lose the memory of their origins. A poet who perhaps knew better than anyone before and after him that miracles and artistic beauty have the same roots can be cited as a prime witness for this – and who therefore, even though he was denigrated by his contemporaries as an anticising heathen, always linked his work to evangelical poetics of miracles throughout his life. This poet would have been exactly 260 years old today, 28 August 2009: The person in question is Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. In the middle of the genius period, in the very years when Goethe was at his most youthful and spirited against the old – and, for example, temporarily stopped writing rhymed verse as a matter of principle – in the middle of these years he wrote a poem – correspondingly unrhymed – entitled “Harzreise im Winter” (Harz Journey in Winter), in which he struggled in 1777 to decide whether he should remain a lawyer in Weimar, where he had been summoned two years earlier, or set off again for freedom. The poem contains a stanza in which he asked for guidance in the third person: “Is on thy psalter, / Father of love, a sound, / To his ear audible, / So refresh his heart!” The requested tone then became audible in a moment of absolute silence, the view from the mountain peak, climbed in a storm at the risk of his life, to the world lying below him and at the same time into his own “unexplored bosom”: “Altar of the loveliest thanks / Becomes him of the dreaded summit / Snow-hanging crest”, and this “loveliest thanks” is the poem that, itself “mysteriously revealed”, sings of the mysterious revelation.

Goethe, of course, had to go to the limits of the physically possible in his mountain hike in order to hear the sound of silence – and today it is even more difficult to even hear such sounds, let alone understand them. The wonders of which Markus reports still had it relatively easy, since at that time there was none of the media pollution that today anaesthetises our senses with an unfiltered flood of foreign-generated impressions. In Bach’s time, if you wanted to hear his music, you had to go to one of the churches where his cantatas were performed on a particular Sunday; and even in Goethe’s time, works of art were available as reproducible engravings, but the real power of their colours or their three-dimensionality only unfolded in personal encounters. Today, thanks to the technical achievements of the 20th century, we are used to seeing the beauty of art. Today, thanks to the technical achievements of the twentieth century, we are accustomed to having the beauty of art available everywhere and at all times, and even when we take the trouble to visit the originals in order to immerse ourselves in the aura of their presence, we are still defencelessly exposed to this media pollution: If our eyes almost want to lose consciousness with happiness in view of the Chagall windows in Zurich Minster, the tourist is not far away who rudely awakens us with the flash of his camera; and if we stand in front of a watercolour by Paul Klee and just begin to hear its sounds in the delicate mother-of-pearl shades of painted music, the mobile phone of the visitor standing next to us will certainly begin to bleat an electronic variant of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries or a similar abomination.

Under these conditions, it is difficult to do what the poet Hilde Domin called for in what I think is one of her most beautiful poems: “Don’t get tired / but hold out your hand to the miracle / quietly / like a bird.” But the fact that this is difficult is precisely the condition that once Markus, and after him Bach and Lehms, then Goethe and finally, with Hilde Domin, also the voice of our present day have identified in the essence of the miracle: To recognise this essence requires an education of the soul, which today perhaps more than ever needs to trace the beauty of art back to its roots in the poetics of the miracle. From the time when the evangelists, as part of their proclamation mission, captured the moving power of Jesus’ miraculous activity in their narratives, through the perfect merging of text and music, as we experience in Bach’s cantatas, to the birth of modern aesthetics, the beauty of art has always been a part of our lives, to the birth of modern aesthetics from the spirit of the biblical rhetoric of revelation, have always taken on the task of preserving individual experiences of being overwhelmed – and above all, of giving them a voice that can redeem us from the deaf-muteness of the moment of experience to communicate even today: “Mind and soul are confounded” so that we “do not grow weary / but hold out our hand to the miracle / quietly / as to a bird”: “He who has ears to hear, let him hear”.

Literature

– Hilde Domin, Nicht müde werden, in: Hilde Domin, Hier. Poems, Frankfurt a. M. 2006

– Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Harzreise im Winter, in: Karl Eibl (ed.), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Sämtliche Gedichte, vol. I: 1756-1799, Frankfurt a. M. 1987

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).