Schwingt freudig euch empor

BWV 036 // For the First Sunday in Advent

(Soar joyfully aloft) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe d’amore I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo.

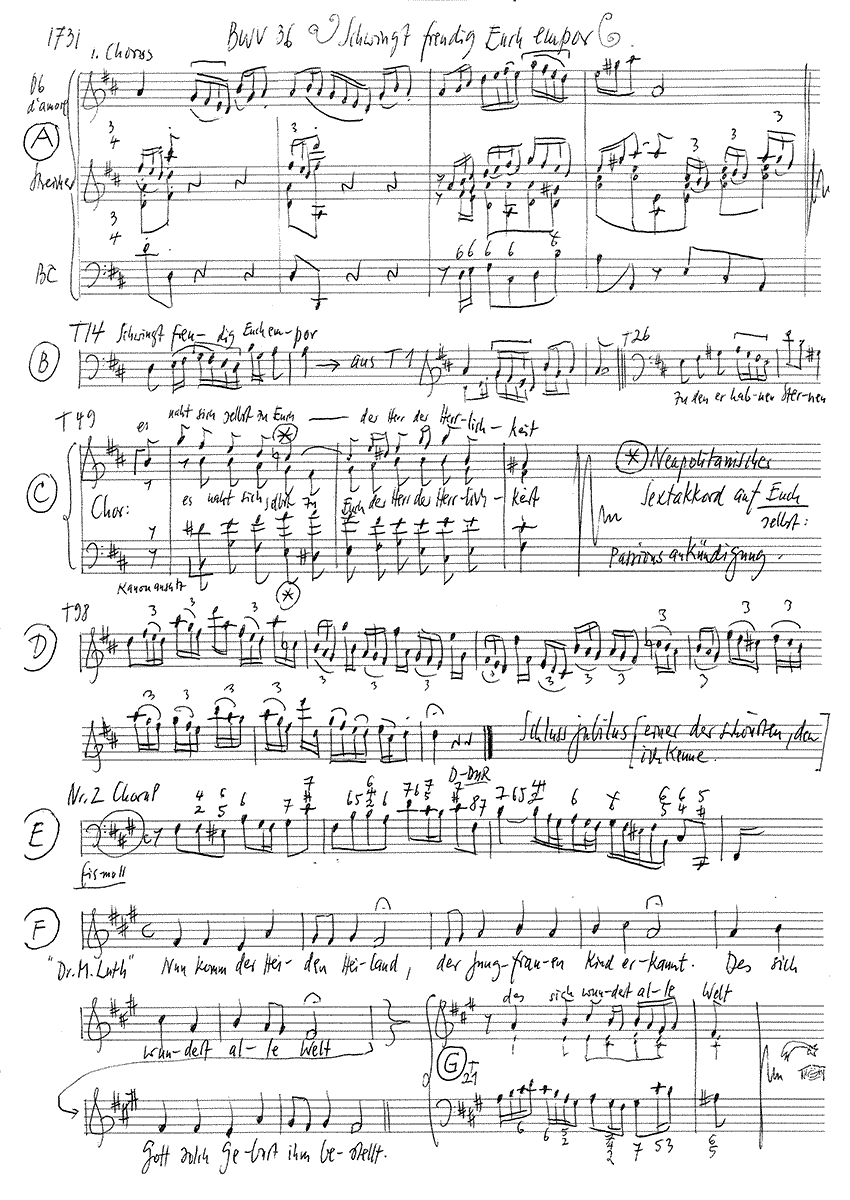

Cantata BWV 36, “Schwingt freudig euch empor!” (Soar joyfully aloft), is a work of clarity and elegance that seems especially well-suited to the preparatory period of Advent – a time that, while not yet festive, still seems illuminated from within by the warm glow of candlelight. This coherent impression, however, is most surprising considering the cantata’s irregular evolution. Initially, Bach borrowed heavily from secular compositions from his Cöthen and Leipzig periods to develop a five-movement sacred cantata (the version passed down by his pupil Kirchenberger), before expanding it in 1731 into a two-part sermon cantata through the addition of three chorale movements. The form of the resulting work is highly unusual for Bach’s mature oeuvre. Indeed, it completely eschews the usual recitatives, employing instead three verses of the hymn “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland!”, lending the work the character of a chorale partita interspersed with free passages. Around 1735, Bach must then have “re-secularised” the cantus-firmus-free movements to produce BWV 36b for a member of the Rivinus family, a well-known Leipzig family of legal scholars.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Jennifer Rudin

Alto

Olivia Heiniger, Antonia Frey, Corinne Grendelmeier Nipp

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Chasper Mani, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

John Holloway (special Guest), Renate Steinmann, Christine Baumann, Silvia Gmür, Sabine Hochstrasser, Martin Korrodi

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Luise Baumgartl, Martin Stadler

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Markus Maerkl

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Urs Widmer

Recording & editing

Recording date

12/14/2007

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 3, 5, 7

Rewritten, perhaps by Christian Friedrich Henrici (Picander),

between 1723 and 1726

Text No. 2, 6, 8

Martin Luther, 1524

Text No. 4

Philipp Nicolai, 1599

Year of composition

1731

In-depth analysis

With its light and buoyant character, the introductory chorus cannot disguise its origins as a secular congratulatory work, although the ascending figure of the music fits perfectly with the sacred text of “amidst the starry grandeur”. In this spirit of elation, the comparatively subdued gesture (“No, wait awhile! Your sound shall not have far to travel”) and the echoing oboe passages render large sections of the movement a musical expression of inner joy.

In the introspective, yet highly expressive chorale duo, “Come now, the nations’ Saviour”, the cantata then turns directly to the theme of Advent. The chorale melody is quoted already in the opening continuo ritornello, in which the expressive, intertwining lines of two oboes call to mind a petit motet in French style. This delicately understated structure is enhanced by the sempre piano instrumentation, in which the timbre of the oboes d’amore perfectly reflects the import of the text.

This tender sentiment is then sustained in the extended tenor aria, a skilful trio setting. Here, the “gentle paces” of godly “love” are hauntingly expressed in a vocal and oboe d’amore duo, ere the twists and turns of the B-section, with its enraptured decent on the words “when she the bridegroom near beholdeth”, provide for a breath-taking interpretation of the sublime meeting of the soul-bride and Christ.

In the vibrant, four-part chorus, “Raise the viols in Cythera”, the thrill of Christmas anticipation is now allowed to emerge. In its earlier sacred version, the seventh verse of the Lutheran hymn (“How am I now so truly glad”) was assigned to this movement of elegant bass passages.

Accompanied by a light-hearted string setting, the second part of the cantata commences with a bass aria – a sonorous welcome to the longed-for “dearest love!”, in which the constant exchange of the striking “Welcome!” head motive between the continuo, vocalist and strings acts as a dialogical gesture. This is followed immediately by “Thou who art the Father like”, a new setting of the cantata’s head chorale in lively triple metre, in which the cantus firmus is assigned to the tenor.

The ensuing soprano aria is musically reminiscent of the tenor aria about godly love from the cantata’s first part. The instruction of “with mute” for the solo violin provides for a literal musical interpretation of the words “muted voices”, thus emphasising the atmosphere of inner rapture that enables this movement, like the whole cantata, to emerge as an apotheosis of the weak, yet hopeful people, whose souls, strengthened by the spirit, cry out their longing and are thus ready to welcome the coming king into their hearts.

The cantata closes with an austere chorale movement on the doxological last verse of the Lutheran chorale “Praise to God, the Father, be”. Despite its experimental form, BWV 36 proves an effective work of strong inner coherence; one that is fully able to forgo the dramatic function of the recitative, while still telling a tale of quiet hope and the promise of fulfilment.

Libretto

Erster Teil

1. Chor

Schwingt freudig euch empor

zu den erhabnen Sternen,

ihr Zungen, die ihr itzt in Zion fröhlich seid!

Doch haltet ein!

Der Schall darf sich nicht weit entfernen,

es naht sich selbst zu euch der Herr

der Herrlichkeit.

2. Choral (Duett Sopran, Alt)

Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland,

der Jungfrauen Kind erkannt,

des sich wundert alle Welt,

Gott solch Geburt ihm bestellt.

3. Arie (Tenor)

Die Liebe zieht mit sanften Schritten

sein Treugeliebtes allgemach.

Gleichwie es eine Braut entzücket,

wenn sie den Bräutigam erblicket,

so folgt ein Herz auch Jesu nach.

4. Choral

Zwingt die Saiten in Cythara

und laßt die süße Musica

ganz freudenreich erschallen,

daß ich möge mit Jesulein,

dem wunderschönen Bräutgam mein,

in steter Liebe wallen!

Singet,

springet,

jubilieret, triumphieret, dankt dem Herren!

Groß ist der König der Ehren.

Zweiter Teil

5. Arie (Bass)

Willkommen, werter Schatz!

Die Lieb und Glaube machet Platz

vor dich in meinem Herzen rein,

zieh bei mir ein!

6. Choral (Tenor)

Der du bist dem Vater gleich,

führ hinaus den Sieg im Fleisch,

daß dein ewig Gotts Gewalt

in uns das krank Fleisch enthalt.

7. Arie (Sopran)

Auch mit gedämpften, schwachen Stimmen

wird Gottes Majestät verehrt.

Denn schallet nur der Geist darbei,

so ist ihm solches ein Geschrei,

das er im Himmel selber hört.

8. Choral

Lob sei Gott, dem Vater ton,

Lob sei Gott, sein’m eingen Sohn,

Lob sei Gott, dem Heilgen Geist,

immer und in Ewigkeit!

Urs Widmer

“Father Tone and Angel Choir”

The most beautiful thing, the easiest thing, would be to simply rave enthusiastically before you about the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, about this ever-new wonder, this work so overwhelmingly rich that it stands like a Matterhorn in the musical hillside of its time. Bach’s music has long since become something like the primordial meter of all music, the DIN standard against which we measure everything that came later, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and even Bartók or Webern. Everything is measured against Bach, even today.

Of course, between the two performances of the cantata with the title line “Schwingt freudig euch empor”, there will also be a few remarks about the music in my words. A cantata text does not live without its music, and the music of this cantata is certainly particularly impressive. But I want to speak here of the text.

It has three authors. One, whose name we no longer know and who may be Christian Friedrich Henrici, who called himself Picander, Philipp Nicolai, to whom we owe the hymn “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” and who had been dead for more than a hundred years, and the most famous of all, who, however, had already died almost two hundred years ago: Martin Luther. His chorale “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland”, which forms something like the backbone of the cantata, was the number-one chorale of the Protestants at the time – everyone knew it by heart – and it is still one of the most popular today. Bach needed or used up many lyricists for his church cantatas; after all, he wrote three hundred church cantatas, many in cycles and for a specific church day. Two hundred of them have survived. This was a massive undertaking. In his first years in Leipzig, from 1723 onwards, Bach wrote about five cantata cycles, i.e. series of about sixty cantatas each for all Sundays and feast days of the church year. Week after week: finishing the text, composing half an hour of music, rehearsing, performing. That was a lot, even for a Bach, and we have to assume that none of the performances was as carefully rehearsed as we are used to today and as we experience it here. There are testimonies from Bach’s contemporaries (and from himself) that suggest to us that much was sung and played prima vista, so to speak. The musicians and singers were probably happy if they hit the note at all and deciphered the text correctly. They hardly had time for a careful interpretation of music and text.

Our cantata BWV 36 “Schwingt freudig euch empor” was also written for a special day, for the first Advent. Today’s performance doesn’t hit the day exactly, but it comes close. The first Advent is not a black day in the church year, like Good Friday, but a joyful one. This shapes the character of the text and the music. “Now come, the Saviour of the Gentiles”: everyone at that time rejoiced together with Luther, and Bach certainly rejoiced without any pretence. True, he was only nine years older than Voltaire, who became – from a Christian point of view – an impudent freethinker, and he was attentive and sensitive enough to sense the early signals of the Enlightenment, which also shook the secure foundations of religiosity. Nevertheless, lines like “Swing joyfully upward, / To the sublime stars, / Ye tongues that now rejoice in Zion!” certainly came naturally from his lips, and he certainly did not doubt that either: “The Lord of glory draws near to you himself.”

The fact that the main part of the text – apart from the Luther chorale and the Nicolai stanza – is anonymous does not mean that Bach took the first and nearest text. On the contrary, he was constantly on the lookout for suitable texts. He was largely his own master, negotiated with librettists (Bach also had a budget that he was not allowed to exceed) and had textbooks printed on his own account. But finding good librettists was not so easy. For one thing, Bach needed a lot of texts, and for another, the ecclesiastical rule over poetry had been broken since Luther and the impersonal, i.e. generally valid and correspondingly easily reproducible sacred style had been undermined. The poets, who were Bach’s contemporaries and no longer Luther’s, no longer preferentially or even exclusively wrote texts that could be used directly for church purposes. Indeed, Luther – like Bach in music – had already been a rather lonely giant of church poetry in his time and remained so. For although the number of theologians writing poetry increased immeasurably in the 17th century, all these parish priests with a penchant for writing – or so those who have eaten their way through this mountain of texts think – can hardly be credited with works of distinction.

Bach sometimes found texts, but he often liked to have them specially prepared for his own needs, with little or no luck of success. His favourite was probably the Leipzig composer Christian Friedrich Henrici, known as Picander – it is by no means certain that he was the author of our cantata – a gifted poet with a lifestyle that, from the Protestant point of view of the time, was open to attack – wine, women and song, it seems – and it sheds a perhaps unexpected light on Bach that he was not at all irritated by Picander’s escapades, but perhaps even found pleasure in them. In any case, he remained on friendly terms with Picander, even though the good society of Leipzig met him with increasing suspicion. This draws our attention to Bach’s non-conformity – one such as he was not a prince’s lackey or a church lamb – no, it was quite inevitable that he would constantly chafe against his surroundings. We who are born later only overlook this time and again because Bach lived neither in enlightened nor revolutionary times. The power of the absolutist ruling masters was still so intact that one was not even allowed to resign from a post one held. One was condemned to one’s profession, even if one no longer wanted to do it or – which became Bach’s case – liked to do it elsewhere. In fact, Bach was imprisoned for a month in 1717 because he wanted to go to Köthen, and then, when he remained unbending, was ungraciously released. The Weimar court records state: “Eod. d. 6. Nov. the previous concert master and court organist Bach was arrested in the magistrate’s chambers because of his stubborn behaviour and his forced resignation, and finally on 2. December the court secretary announced his resignation and at the same time released him from arrest. The French horn player Adam Andreas Reichardt from Bach’s Weimar orchestra fared even worse: whenever he asked to be released, he was sentenced to one hundred lashes and imprisonment. After he had secretly absconded – which is very understandable – he was declared an outlaw and hanged in effigie. Bach, after all, made a somewhat legal career. Even if his employers all did not know what they had in him – the greatest musician of his time, competing with the distant Handel, who belonged to the English – his skills were not ignored. After all, he was and was considered the most important organ virtuoso of his time, able to outplay any competitor and sometimes did so. Bach belonged to those – like Vivaldi in faraway Venice – who were able to improvise without effort, almost like jazz musicians today. A harmonic specification was enough for him, and he set to work.

An openly psychologising setting of a text was alien to him – and to his entire time – even if he could certainly add an individual painful sound to a word of pain. But, in keeping with the habits of his epoch, he had no problem using a wide variety of texts for the same piece of music. Our cantata “Schwingt freudig euch empor” is also a so-called parody. A parody, not in the modern sense of the word, i.e. not a verbalization, and the term had nothing pejorative about it. It simply meant that the composer used a new text for music that already existed. The cantata BWV 36 is to a large extent such a parody, for it had already existed before – as early as 1725 – with a secular text that had nothing to do with the first Advent. It was a birthday cantata for a teacher whose text, although thoroughly secular, is not too far removed from the sense and spirit of the church cantata. Or, conversely, the church text is, in keeping with the occasion, joyful and cheerful, for he, too, is looking forward to a birthday, the one in Bethlehem. Bach subsequently used the cantata several times, for example for the birthday of Princess Charlotte Friederike Wilhelmine zu Anhalt-Köthen (1726), then also in honour of a member of the Leipzig legal family Rivinus, and finally as a church cantata for the first Advent. Always the same music, almost. For in the version with the text we hear today, Bach must have found parts of the first version too external and reshaped them. Nevertheless, the proximity to the original birthday cantata cannot be ignored.

Such a procedure was not only efficient secondary use – that too, of course – but also saved beautiful things from being heard only once by a handful of birthday guests. Now it was heard again, in a good place and in front of an audience that, beyond its ecclesiastical utility value, was taken in by the beauty of Bach’s music, which was still unusual at the time. Bach was not yet the measure of all things for his contemporaries, especially for the more inexperienced among them; on the contrary, he irritated all those who wanted to hold on to what they were used to. He was infinitely more powerful, passionate, sensual than the church musicians around him, even than his predecessor, Johann Kuhnau, who had never surprised his church flock with unusual or violent compositions. Bach’s music particularly frightened the orthodox Protestant members of the council who were his employers. They feared the operatic, the dramatic, the lively like the devil fears holy water. The fact that music – and the texts used for it – could also trigger joy was abhorrent to their strict understanding of faith, so much so, incidentally, that Bach became perhaps the only composer in history who had to undertake in his contract not to write music that was too good. The contract of employment instructed Bach to “arrange the music in such a way that it does not last too long, and that it is also composed in such a way that it does not come across as operatic, but rather encourages the listeners to devotion”.

As we know, Bach did not adhere to this. He was too much of a theatricalist and melodist to have been able or willing to follow the commandment to renounce all sensuality in his texts and music. Our cantata is an example of this. It dates from 1731, Bach’s mature years. “Soar joyfully to the sublime stars”: these are its first words. And so it continues: “Ye tongues that now rejoice in Zion! / But hold your peace! / The sound may not depart, / It draws near to you itself the Lord of glory.”

In the birthday cantata for Lord Rivinus, set to the same music, it reads like this: “Joy stirs, raise the cheerful notes, / For this beautiful day leaves no one quiet. / Pursue the impulse, only away, you faithful sons of the Muses, / And now deliver the toll in pious wishes!”

This, of course, is not the same thing. There are significant differences between the coming birth of Christ and the birth of the jurist Rivinus. Nevertheless, even in the church cantata, a tone of unrestricted joy dominates from beginning to end. Yes, right from the tenor’s aria, the text becomes quite worldly, openly sensual, to be more precise. It speaks of love, and: “Just as a bride is delighted / When she sees her bridegroom, / So does a heart follow Jesus”. And already we are – although in a church cantata! – in the midst of the most beautiful wedding feast: “Force the strings in Cythara / and let the sweet musica / resound joyfully, / that I may wave with Jesulein, the beautiful bridegroom mine, / in constant love!” This is how a bride in love speaks, even if she has a male voice here, so we should all feel, we listeners should all swell in love, and indeed “with Jesulein, the beautiful bridegroom”, as it says in the text. The diminutive and the still very young age of the bridegroom – we are four weeks away from his birth – make the surging of our love somewhat innocent. The erotic connotation does not completely disappear from the text. The tone of sensual pleasure is maintained until the end, until just before the end. “Welcome, dear darling!” the coming Saviour is greeted. “Move in with me!” The music underlines the pleasure of the text. However, I will not deny you my feeling that the texts of the cantata do not reach anywhere near the heights of their setting either. When in the Protestant church – after Luther, after Gerhardt, after Gellert – the poetic force had long since died out, it only experienced – we are the late ear-witnesses today – its climax in music. Bach’s music, as Walter Muschg, a great connoisseur of the poetry of the time, puts it, “towers like a pyramid into modern times and gives them a concept of the kind of art that is created for the service of God”. Only at the very end does Bach take back the secular tone. He places Luther’s famous verses at the end: “Praise be to God the Father ‘ton, / Praise be to God his only Son, / Praise be to God the Holy Spirit, / Forever and ever!” I am moved by Luther’s sure piety – I live in other times, sure piety has left me’ but I still wonder every time I hear the line “Praise be to God the Father ‘ton” why the Father is called “Ton”. I thought he was called God. I guess it’s like that line in the beautiful Christmas carol, “High above floats jubilant the little angels’ choir”. Even as a child, I always assumed that the angel hovering high above was called the choir, the angel choir, an unusual name, but not everything is the same with angels as it is with us. All the more so with God the Father. So may Father Tone and the little angel choir guide us safely through the dark pre-Christmas season, into which this cantata brings so much light.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).