Wer da gläubet und getauft wird

BWV 037 // Exaudi

(Who believeth and is baptized) for Exaudi (The Sunday after Ascension), for soprano, alto, tenor and bass; oboe d’amore I+II, oboe da caccia I+II, violoncello piccolo, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

So seid nun mässig und nüchtern zum Gebet. Vor allen Dingen aber habt untereinander eine inbrünstige Liebe; denn die Liebe deckt auch der Sünden Menge. Seid gastfrei untereinander ohne Murren. Und dienet einander, ein jeglicher mit der Gabe, die er empfangen hat, als die guten Haushalter der mancherlei Gnade Gottes; so jemand redet, dass er’s rede als Gottes Wort; so jemand ein Amt hat, dass er’s tue aus dem Vermögen, das Gott darreicht, auf dass in allen Dingen Gott gepriesen werde durch Jesum Christum, welchem sei Ehre und Gewalt von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit! Amen.

Wenn aber der Tröster kommen wird, welchen ich euch senden werde vom Vater, der Geist der Wahrheit, der vom Vater ausgeht, der wird zeugen von mir. Und ihr werdet auch zeugen; denn ihr seid von Anfang bei mir gewesen. Solches habe ich zu euch geredet, dass ihr euch nicht ärgert. Sie werden euch in den Bann tun. Es kommt aber die Zeit, dass wer euch tötet, wird meinen, er tue Gott einen Dienst daran. Und solches werden sie euch darum tun, dass sie weder meinen Vater noch mich erkennen. Aber solches habe ich zu euch geredet, auf dass, wenn die Zeit kommen wird, ihr daran gedenket, dass ich’s euch gesagt habe. Solches aber habe ich euch von Anfang an nicht gesagt; denn ich war bei euch.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Stephanie Pfeffer, Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin

Alto

Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Jan Thomer, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Tobias Mäthger, Sören Richter

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Valentin Parli, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Lenka Torgersen, Ildikó Sajgó, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Judith von der Goltz

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe d’amore

Katharina Arfken, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Giovanni Battista Graziadio

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Heidi Eisenhut

Recording & editing

Recording date

21/05/2021

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Composer of chorale interlude, chorale No. 6 “Den Glauben mir verleihe”

Nicola Cumer

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First Performance

18 May 1724, Leipzig

Text

Mark 16:16 (movement 1); Philipp Nicolai (movement 3); Johann Kolrose (movement 6); unknown (movements 2, 4, 5)

In-depth analysis

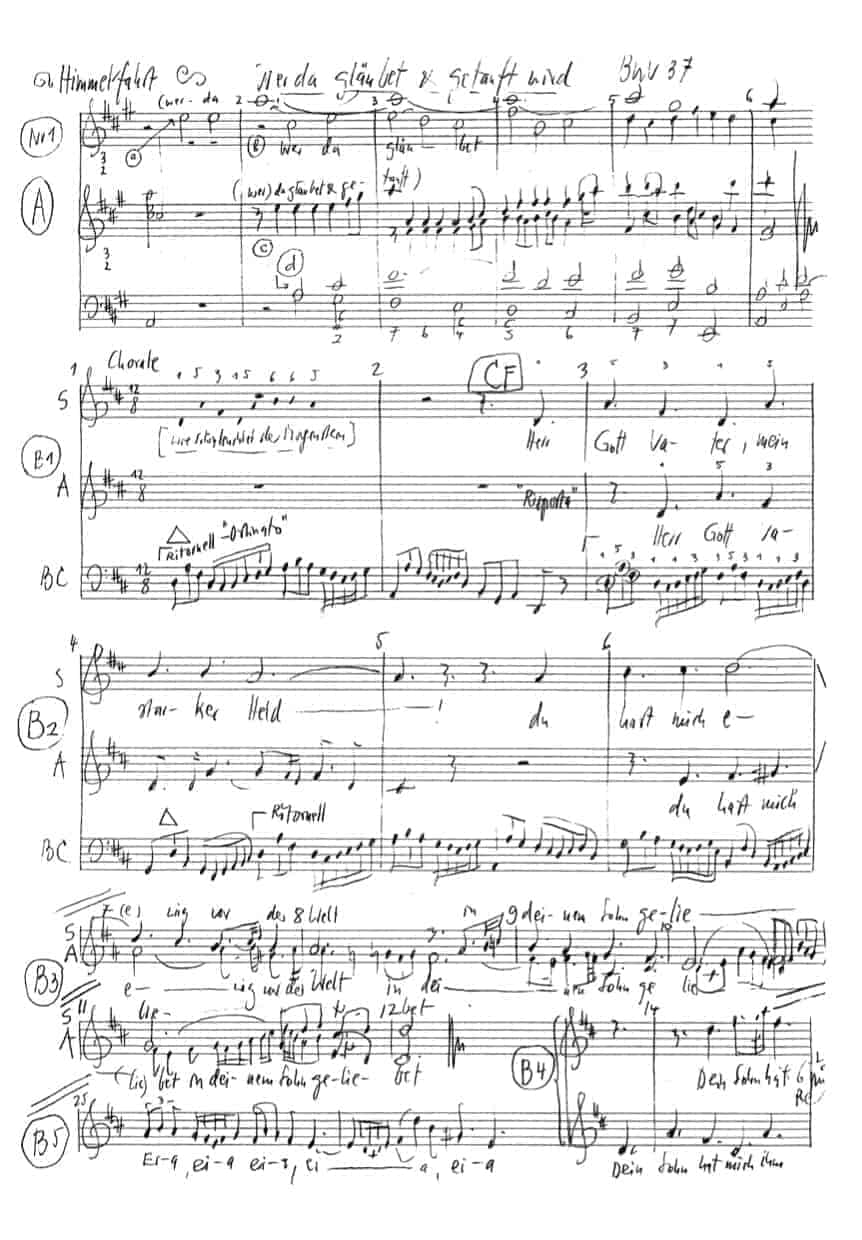

Composed in 1724, BWV 37 “Wer da gläubet und getauft wird” (Who believeth and is baptised) was the first cantata Bach wrote for Ascension Day. He later revived the work, which is set to a text by an unknown librettist, to celebrate the same feast day in 1731.

While not especially long, the introductory chorus, a setting of a verse from the Gospel of Mark, is replete with buoyant energy. The speech-like motif of the strings and two oboes d’amore in the orchestral prelude introduces the uplifting gesture “Wer da gläubet” (Who believeth) and also possibly makes a covert reference to the hymn line “Dies sind die heilgen zehn Gebot” (These are the sacred Ten Commandments), thus integrating the law of Moses in Jesus’s New Covenant, in line with the unified approach to Bible interpretation in Bach’s day. In this brightly embracing A major setting, faith and baptism are rendered as an earnest yet blissful happening to which all are most cordially invited. In this movement more than most of Bach’s cantata choruses, it is abundantly clear that even Bach’s trailblazing compositional skills are rooted in a multi-generational church music project shared and developed by masters such as Telemann, Graupner and Stölzel.

When performed using solely the surviving materials for tenor and continuo, the following aria is considerably lacking in brilliance – a problem that has hardly escaped the notice of scholars and critics. To be sure, the vocal cantilena alone, with its mixture of fluidity and firmness, is doubtless suited to portraying the connection between faith and love. However, because the incomplete set of remaining original parts justifies the assumption that at least one solo part is missing, certain audible gaps – especially in the continuo part – can be both explained and remedied; the additional violin part composed by Masato Suzuki selected for this recording is our contribution to the discussion on this score.

In any case, a lack of energy can hardly be ascribed to the opening of the following movement, which introduces a chorale setting for soprano and alto voices with free imitations over a continuo part. In this increasingly ecstatic duo, the Father-Son aspect of God’s Ascension as well as the bride-bridegroom relationship between Jesus and the faithful soul as portrayed in this hymn verse by Philipp Nicolai find delightful expression.

After so much bliss in Christ, the following bass recitative again bolsters the pillars of Lutheran doctrine by downplaying the salvific effect of “gute Werke” (good works) and highlighting faith as the basis of all justification before God. Alone the majestically shimmering string accompaniment lends the opening question as to whether and how a mortal may dare to look upon God’s countenance the character of a warning.

The following aria neither resolves this conundrum nor does it soften the serious nature of the question. It does, however, provide the necessary strength to accept the requirement of baptism and faith as a life-giving opportunity. “Der Glaube schafft der Seele Flügel” (Belief provides the soul with pinions) – set not in a light major key but with energetic rhythms and uplifting figures, the music lends the courage needed to preserve Jesus’ “seal of mercy” in the face of all temptation.

Johann Kolrose’s chorale verse “Den Glauben mir verleihe” (Belief bestow upon me) serves as an astonishingly content-rich conclusion to a cantata that, at times, has been described as too subdued for a high feast day – but that nonetheless tells a great deal about humankind, its place in the world and creation, and the difficult path to true empathy towards ourselves and our neighbours. If the hidden subtleties in this apparently simple four-part setting are anything to go by, Bach, at least, benefitted greatly from contemplating this libretto.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Wer da gläubet und getauft wird, der wird selig werden.»

2. Arie — Tenor

Der Glaube ist das Pfand der Liebe,

die Jesus für die Seinen hegt.

Drum hat er bloß aus Liebestriebe,

da er ins Lebensbuch mich schriebe,

mir dieses Kleinod beigelegt.

3. Choral — Duett: Sopran, Alt

Herr Gott Vater, mein starker Held!

du hast mich ewig vor der Welt

in deinem Sohn geliebet.

Dein Sohn hat mich ihm selbst vertraut,

er ist mein Schatz, ich bin sein’ Braut,

sehr hoch in ihm erfreuet.

Eia, eia!

Himmlisch Leben wird er geben mir dort oben;

ewig soll mein Herz ihn loben.

4. Rezitativ — Bass

Ihr Sterblichen, verlanget ihr

mit mir

das Antlitz Gottes anzuschauen?

So dürft ihr nicht auf gute Werke bauen;

denn ob sich wohl ein Christ

muß in den guten Werken üben,

weil es der ernste Wille Gottes ist,

so macht der Glaube doch allein,

daß wir vor Gott gerecht und selig sein.

5. Arie — Bass

Der Glaube schafft der Seele Flügel,

daß sie sich in den Himmel schwingt,

die Taufe ist das Gnadensiegel,

das uns den Segen Gottes bringt;

und daher heißt ein selger Christ,

wer gläubet und getaufet ist.

6. Choral

Den Glauben mir verleihe

an dein’ Sohn, Jesum Christ, mein Sünd mir auch

verzeihe allhier zu dieser Frist.

Du wirst mir nicht versagen, was du verheißen hast,

daß er mein Sünd tu tragen und lös mich von der Last.

Heidi Eisenhut

BWV 37 | He who believes and is baptised

45 years ago last Sunday I was baptised in the Protestant Reformed Church in Rehetobel. When I recently tracked down this date in the photo album that my mother had lovingly arranged, I fell silent at the rediscovery of the two pages dedicated to my baptism in words and pictures.

Ladies and gentlemen, dear listeners, I don’t know how you feel if, like me, you were baptised as an infant: Do you know your baptism day? And if so, what does it mean to you? What does your baptism mean to you?

I awkwardly swore at the two pages in the album throughout. What does my baptism mean to me? Carefully, I opened the envelope pasted into the album, bearing my name in an ancient script. Inside was the baptismal booklet, which contains prayers and texts for baptism. On the first page I came across my baptismal certificate, signed by “J. Zolliker Pfr.”, sealed by a stamp of the Protestant parish office. Johann Jakob Zolliker was pastor in Rehetobel from 1949 until the end of May 1976. My baptism was probably his last in office. I am fascinated by the thought of having been baptised by a Johann. Even if this Johann was called by his second name, Jakob. “Jakob” was also the name of my father and my paternal grandfather, before everyone from my great-grandfather back to my great-great-great-great-grandfather was called Johannes. Jacob means “heel holder” or “(God) protects / protect”, John translated means “God is gracious” or “God is kind”.

I had put the baptismal booklet next to the album while I pondered the two names and their meanings, my thoughts guiding me to the question of what makes people believe over the centuries that God protects and is gracious to them. In the process, my gaze brushed against the two photos at the bottom of the first album page, on which I am pictured, wrapped in a white christening robe, loved and protected, once with my godparents and once with my parents. Between the photos my mother had written in beautiful handwriting the baptismal verse from the Book of Isaiah chosen by the priest: “For the mountains shall depart and the hills shall fall: but my grace shall not depart from thee, neither shall the covenant of my peace fail, saith the Lord thy merciful God. (Is. 54, 10) God will always be merciful, even if this is often not immediately apparent, promises this sentence, which is historically assigned to the time of the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BC. The basic trust that God is involved, that I can hope that everything has a meaning and that justice, peace and love ultimately prevail, was and is comfort and light for many people. That can be liberating! “Faith gives wings to the soul so that it soars into the heavens” we read in our cantata for Ascension Day. Baptism is the “seal of grace”, the privilege to accept faith as a “pledge of love” and through it to shape one’s own life and attain eternal life.

I picked up my baptismal booklet once again to give its contents a second chance, but I didn’t get as far as the texts. I had discovered the title vignette, an illustration by Konrad Grimmer (1915-1950) from the 1940s (Fig. 1). It shows a band of clouds from which the Holy Spirit descends in the form of a dove onto a cup-shaped baptismal font filled with water. The water in the basin is not still, but undulating, as if moved by an invisible hand.

I didn’t have to think long about where I had already encountered this depiction in a similar form. All I had to do was close my eyes – and I would like to invite you, dear listeners, to accompany me on a little excursion that first takes us to the monastery of St. Johann in Müstair in the Münstertal, in the easternmost tip of Switzerland, and then via Italy back to eastern Switzerland, to the church in Trogen.

It was a Sunday morning in July 2019. For years, I had once again spent the night in Müstair, a few metres from the monastery of St. Johann. The awakening day lured me to the monastery church, a place I have liked since I knew it. I had time. A Benedictine nun was praying quietly next to the statue of Charlemagne, the legendary founder of the monastery. She didn’t notice me, and I was careful not to disturb her. I sat down in one of the front rows of benches on the left side of the nave. From there I had a clear view of the north wall, in which only one thing interested me: the Romanesque stucco panel set into it with the depiction of the baptism of Jesus (Fig. 2).

For a long time I pondered what fascinates me so much about this 1000-year-old stucco relief. I think it is my amazement that its perfection of form, in a thoroughly independent interpretation of the motif, has been able to radiate confidence over the centuries. Jesus Christ stands frontally in the wave-like piled up waters of the Jordan. In the centre of the depiction rests his navel, which is shaped as an eye. His real eyes are alert and round, his facial expression invitingly friendly. The baptism by John has already been performed. The Holy Spirit in the form of a dove descending from a curtain of clouds and the open left hand over the heart indicate that Christ receives God’s blessing (Mark 1:9-11) and with his right hand passes it on in the name of the Trinity to John, who accepts it in a humble posture with open hands. On the other side of the Jordan, an angel with the robe of the Lord is waiting, for Christ would rise from the water in the next moment. This impressive snapshot makes the dove’s beak merge with Christ’s crown and navel to form a line rooted in the broad crest of the wave, connecting heaven and earth. Two columns flank the composition, which was originally painted. They consolidate the calm and constancy that the structure radiates – despite the dynamism inherent in receiving and passing on the blessing.

The depiction of the baptism of Jesus has been known as a motif in Christian iconography for over 1600 years. As a mosaic in the domes of baptisteries, as a relief on baptismal fonts and vessels, as a painting, book illustration or marquetry work, it has left a narrative trail through the centuries that made me pause in thought in the pew in view of our fast-paced, short-lived, image- and charm-rich times. The self-confident depiction of Christ as centre and mediator is one of the nuances that makes the baptismal relief of Müstair, at least for me, something very special about which I would like to continue to gather information and reflect.

With such thoughts, I left the wonderful place. The small travel group to which I belonged continued the journey to Italy. The question of baptism receded into the background. Other things were more important, until a good week later, on the autostrada between Livorno and Genoa, the exit “Carrara” instantly called me back to the baptism. This time not to a monastery in the mountains, but to a church – ours – in the hills. The trigger was once again a Johann: the textile merchant Johannes Zellweger-Hirzel (1730-1802). Around 1781, he had a baptismal font made of Carrara marble made in Genoa for the new church being built in his home town of Trogen and transported across the Alps (Fig. 3).

The gem has a circular baptismal font sitting on a shaft in the shape of a candelabra, entwined with acanthus leaves. An artistically forged octagonal (!) lattice offers protection. And to all those who look even closer, the wooden lid of the baptismal font, which at first seems inconspicuous, shows an inlay depicting the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan (Fig. 4). The skin parts of Christ and John and the dove are made of precious ivory! This Trogen baptismal font with its transalpine history was originally not in its present location in the choir, but in front of the choir arch in the nave (Fig. 5), directly under the ceiling painting depicting Christ blessing the children (Luke 18:16) (Fig. 6).

As the integrating centre of the Reformed faith community, it was surrounded by pews that filled the nave, the gallery and the entire choir. As the navel of a microcosm, his water and the hand and words of the baptising minister gave and still give the privilege of belonging.

You have noticed, the excursion is over and I am back in the here and now. The dove swooping down from the curtain of clouds saved me from having to deal with the second clause of Mark 16:16 in my baptismal booklet: “He who believes and is baptised will be saved”, Johann Sebastian Bach set to music. “But he who does not believe will be condemned”, he did not set to music. I like this omission. For me, cultural history, the positive and creative things of the centuries, the manifold forms of expression of the visual and performing arts, music and literature and the miraculous things that emerge from them, such as the baptismal relief of Müstair and the baptismal font of Trogen, are encouragement par excellence. How much knowledge, skill, dedication and good will is contained in all these testimonies up to the present day! And if we add to this the goodwill of people who are selflessly there for others, who help where support is needed, then for me the friendly face of Christ on the stucco relief in the north wall of Müstair stands for the confidence that faith can be understood as something that drives us to use our abilities and talents in this world in such a way that we succeed in sharing joy and love. This can make us content, happy and fulfilled.

Ladies and gentlemen, dear fellow human beings from near and far, in this spirit I wish you much joy in listening to our cantata for the second time today and for the coming Pentecost days time to reflect – and to be.

—-

Picture credits: Fig. 1 © EVZ-Verlag Zurich, illustration: Konrad Grimmer (1915-1950); Fig. 2 © Stiftung Pro Kloster St. Johann Müstair, photo: Suzanne Fibbi-Aeppli, 1987; Fig. 3-6 © Kantonsbibliothek Appenzell Ausserrhoden.

Many thanks to Prof. Dr. Jürg Goll, Müstair, and Prof. Dr. Paul Michel, Zurich, for the inspiring exchange on the baptismal relief in Müstair.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).