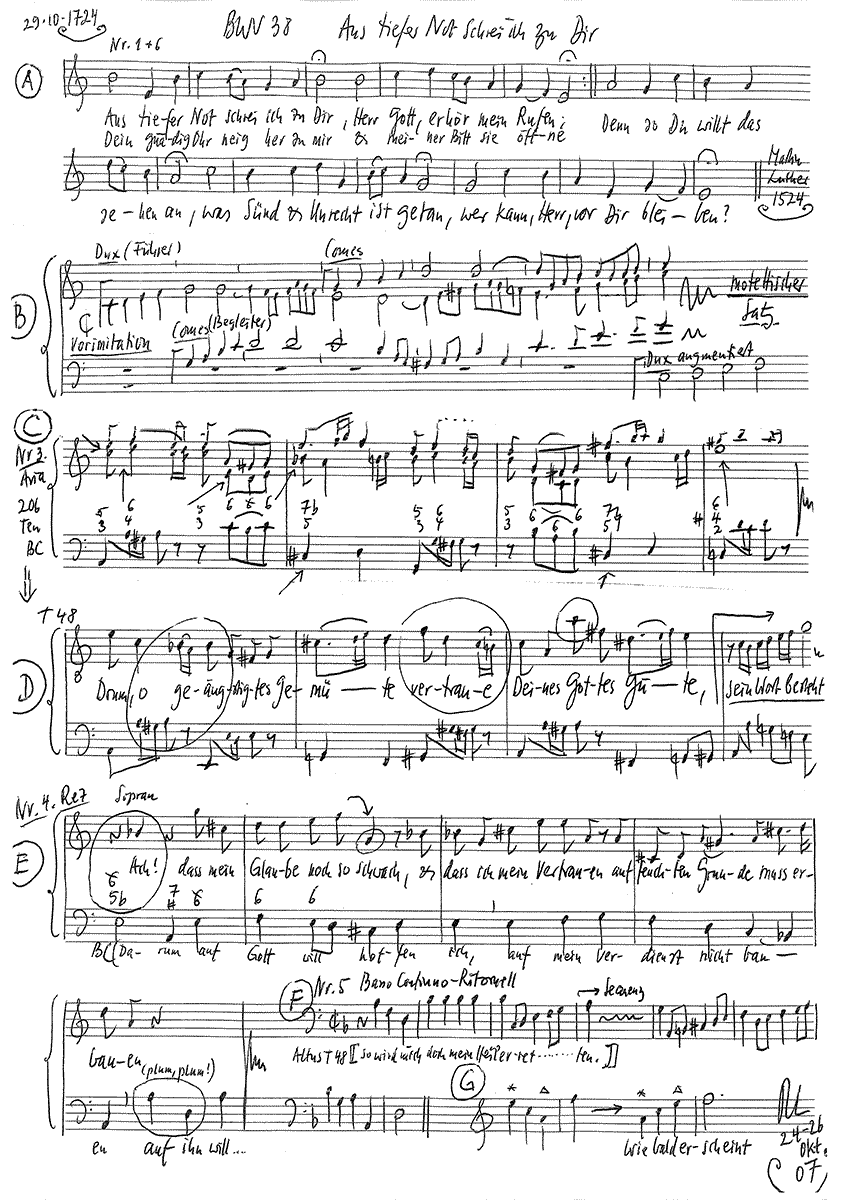

Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu Dir

BWV 038 // For the Twenty-first Sunday after Trinity

(In deep distress I cry to Thee) for soprano, alto and tenor, vocal ensemble, trombone I–IV, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo.

First performed on 29 October 1724, the cantata “Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir” (In deep distress I cry to thee), opens with a motet-style introductory chorus underscored by trombones – a choice of form and instrumentation most fitting to the venerated hymn on which the movement is based, namely Martin Luther’s version of Psalm 130. It seems that the hymn’s earnest character and distinctive Phrygian tonality made a composition in stile antico particularly appropriate; indeed, Bach also used this style for his six-part organ setting of the same hymn (BWV 686).

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Jennifer Rudin

Alto

Antonia Frey, Jan Börner, Lea Scherer, Olivia Heiniger

Tenor

Nicolas Savoy, Manuel Gerber, Marcel Fässler

Bass

Philippe Rayot, Matthias Ebner, Othmar Sturm

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Livia Wiersich

Viola

Joanna Bilger

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Meike Gueldenhaupt, Gilles Vanssons

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trombone

Ulrich Eichenberger, Wolfgang Schmid, Christian Braun, Christian Brühwiler

Organ

Ives Bilger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Robert Nef

Recording & editing

Recording date

06/06/2007

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 4, 6

Martin Luther, 1524

Text No. 2, 3, 5

Rearrangement by an unknown writer

First performance

29 October 1724

In-depth analysis

First performed on 29 October 1724, the cantata “Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir” (In deep distress I cry to thee), opens with a motet-style introductory chorus underscored by trombones – a choice of form and instrumentation most fitting to the venerated hymn on which the movement is based, namely Martin Luther’s version of Psalm 130. It seems that the hymn’s earnest character and distinctive Phrygian tonality made a composition in stile antico particularly appropriate; indeed, Bach also used this style for his six-part organ setting of the same hymn (BWV 686). The chorus opens with dense imitation in the lower voices, preparing each entry of the chorale melody in the soprano voice. In the closing lines, a pedal point on the note E serves as an effective means of both building tension and interpreting the text. While the sustained note reflects the word “stand”, the overlying harmonic tension reveals that mortal sinners indeed cannot stand before God. As such, Bach’s rendering of the question “Who can, Lord, stand before thee?” contains at one and the same time a damning response that charges the cantata with a pervading sense of existential woe.

The following alto recitative addresses this admission of sin by employing the classic Protestant tenet of justification by faith: “In Jesus’ mercy will alone our comfort be and our forgiveness rest”. Yet, in good Lutheran tradition, the faith needed to secure the promised comfort is lacking – the remaining lines are dedicated to this question of faith and the dilemma of overcoming affliction to attain peace of mind. The tenor aria then introduces a soothing turnaround, with the solo part weaving between the cantabile woodwind lines and an edgy basso continuo – an unusual voicing and a veritable “comfort amidst the suffering”. The subtlety of Bach’s compositional mastery is particularly apparent here in the concise continuo figure that not only culminates in a dissonant leap on the word “suffering”, but equally creates a rocking effect that reflects the word “comfort”.

The soprano recitative is marked “a battuta” (in strict time), perhaps unsurprisingly considering that the chorale melody is played through in full by the continuo. This approach lends the movement a certain aria-like quality, while still allowing for a convincing rendering of the fraught text.

The trio aria opens with a basso continuo ritornello that draws the listener immediately into the movement through its penetrating descending figure. The autonomy of this element enables Bach to uphold structural constancy in the face of an enticing variety of images in the libretto. While the intertwined descending lines echo the “fetters” of despair in the first vocal passage, this descent is effectively reversed by an ascending broken triad (“How soon appears the hopeful morning”) at the beginning of the second section. Nevertheless, by reverting to the music of the tragic opening for the closing phrase “upon the night of woe and sorrow”, and applying the basso continuo ritornello in the vocal parts, Bach ends the movement with a clear-sighted, rather than pessimistic, message on the persistence of suffering, despair and doubt. A chorale on the last verse of the Lutheran hymn, once again underscored by the dark timbre of the trombones, closes this extraordinarily expressive work.

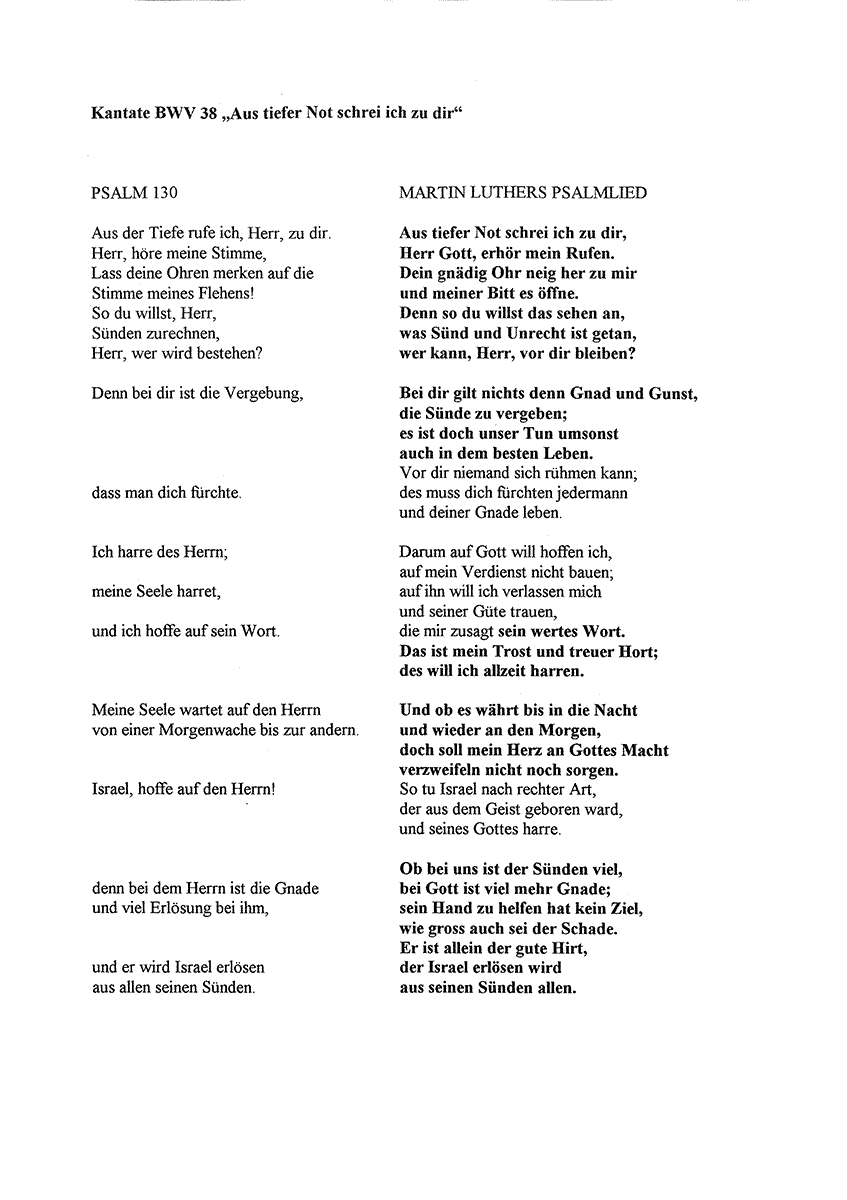

Libretto

1. Chor

Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir

Herr Gott, erhör mein Rufen;

dein’ gnädig Ohr’ neig her zu mir

und meiner Bitt sie öffne.

Denn so du willt das sehen an,

was Sünd und Unrecht ist getan,

wer kann, Herr, vor dir bleiben?

2. Rezitativ (Alt)

In Jesu Gnade wird allein

der Trost vor uns und die Vergebung sein,

weil durch des Satans Trug und List

der Menschen ganzes Leben

vor Gott ein Sündengreuel ist.

Was könnte nun die Geistesfreudigkeit

zu unserm Beten geben,

wo Jesu Geist und Wort

nicht neue Wunder tun?

3. Arie (Tenor)

Ich höre mitten in den Leiden

ein Trostwort, so mein Jesus spricht.

Drum, o geängstigtes Gemüte,

vertraue deines Gottes Güte,

sein Wort besteht und fehlet nicht,

sein Trost wird niemals von dir scheiden!

4. Rezitativ (Sopran) und Choral

Ach! dass mein Glaube noch so schwach,

und dass ich mein Vertrauen

auf feuchtem Grunde muss erbauen!

Wie ofte müssen neue Zeichen

mein Herz erweichen!

Wie? kennst du deinen Helfer nicht,

der nur ein einzig Trostwort spricht,

und gleich erscheint,

eh deine Schwachheit es vermeint,

die Rettungsstunde.

Vertraue nur der Allmachtshand

und seiner Wahrheit Munde!

5. Arie (Terzett Sopran, Alt, Bass)

Wenn meine Trübsal als mit Ketten

ein Unglück an dem andern hält,

so wird mich doch mein Heil erretten,

dass alles plötzlich von mir fällt.

Wie bald erscheint des Trostes Morgen

auf diese Nacht der Not und Sorgen!

6. Choral

Ob bei uns ist der Sünden viel,

bei Gott ist viel mehr Gnade;

sein Hand zu helfen hat kein Ziel,

wie gross auch sei der Schade.

Er ist allein der gute Hirt,

der Israel erlösen wird

aus seinen Sünden allen.

Robert Nef

“Of the distress of words and the consolation of music”.

“Music, word and cry” – thoughts on the relationship of “musica e parole”.

Theologians know the problem of making original texts understandable, the problem of double translation, first into German and then into today’s use of language and symbols, without falsification, without false ingratiation, true to Luther’s motto “Das Wort sie sollen lassen stahn”.

On the basis of individual passages from the choral cantata “Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir” (I cry to you from deep distress) – Martin Luther’s rewriting of the 130th Psalm, which led to the song of the same name – I would like to express some thoughts on a problem that is important in music history and music theory: the fundamental question of the translation of the word into music and of music into the word, of the relationship between word and music, a problem that confronts every composer of vocal music. It also plays a major role in Bach’s literature.

Why – this question should be asked at the outset – does music in many cases become outdated much less quickly than texts? Do we have to compose music today instead of writing texts if we want to still be understood in 250 years? Is the goal of being understood later at all legitimate? Shouldn’t one limit oneself to at least being understandable today? In fact, I don’t believe that we preserve cultural heritage by distorting it to suit the tastes of the time. It is rather a matter of identifying and preserving what is valuable as such, even in times of lower demand, in order to hope for “the consolation of tomorrow”, as it says in the cantata text.

This may be true for literature, the visual arts and architecture: Only the highest quality can really endure, but what is built “on moist ground” according to the terminology of the cantata text, what “exists and does not fail”, cannot be conclusively decided from a human perspective. And that is just as well.

The words of most of Bach’s lyricists, which are by no means always particularly artfully, even bumpily, put together, survive thanks to music and thanks to the fact that language, as a cultural storehouse of the first order, is always more intelligent than the people who use it, more intelligent also than the poets. Bach did not simply set the words to music, he got to the bottom of their meaning and their sound and transposed both musically – as an ingenious decomposer and composer. To a certain extent, he was a translator, a mediator even between differently networked communication systems that each of us probably intuitively masters. It is therefore probably no coincidence that the text of the cantata “Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir” (I cry to you from deep distress) says: “Wie oftte müssen neue Zeichen mein Herz erweichen?”

Texts formally unsuitable for music?

In his great Bach monograph, Albert Schweitzer devoted an entire chapter to the subject of what Bach’s word and tone are like. Schweitzer warns against a hasty disregard for the poets from whose texts Bach chose. “The relationship between Bach’s music and his texts is as lively as can be imagined. This is already evident in the outward appearance. The structure of the musical movement is not adapted by him to the structure of the word movement with more or less art, but is identical with it.”

Schweitzer generally considers Bach’s music to be declamatory rather than melodic. For him, a Bachian theme is an “invented sentence, which by chance, as by an ever-repeating miracle, takes melodic shape.” But if a work of art is a mixture of invention, design and chance, then the term miracle is justified. Every successful work of art is a miracle. And it is part of the essence of the miracle that one believes in it even, and especially, when one cannot explain it, which, for example, is known to be the case with love.

Here, our love for Bach is not to be talked down with the subtle musical-scientific-aesthetic observations of Albert Schweitzer or others. “We don’t want to talk our love to pieces” is the self-deprecating line at the end of Ingmar Bergmann’s award-winning film “Scenes from a Marriage” – and this after the whole film contains nothing but talking love to pieces … I would like to make one last reference to the theologian Albert Schweitzer: In connection with the theme of “musica e parole”, Schweitzer’s statement seems to me remarkable: “His (Bach’s, R.N.) texts are, formally considered, as unsuitable for music as is conceivable. A Bible verse does not form a musical period, not even a linguistic one, since it is not born out of a rhythmic feeling but out of the necessity of translation. And it was no better for the free texts that the librettists supplied him with. They, too, have no inner unity, since they are laboriously pieced together from Bible and hymnbook reminiscences. But if one reads the same sentences later in Bach’s music, they suddenly stand in a coherent musical period.”

It is not possible here to reflect all the musicological literature on the subject of “word and music”. However, in connection with the primacy of music, I would merely like to mark my own distance from a view that has long been outdated among musicologists and connoisseurs, but is still held in cultural bourgeois circles – especially with regard to operas and Mozart operas in particular. There are still music lovers who confuse a vocal work with a symphony and believe that one can simply indulge in the pleasure of the melodies and ignore the text, since it is of inferior quality anyway. Today’s performance practice in the original language, which is unfamiliar to the average audience, strongly counters this opinion.

It is therefore worth taking a closer look at what the composers themselves said about the question of who should serve whom, the music of the language or the language of the music? The controversy over the status of music and words was even addressed in a short opera by Antonio Salieri. It is entitled “Prima la musica e poi le parole – First the music and then the words” (A divertimento teatrale in one act on a text by Giovanni Battista Casti). Mozart performed the short opera “Der Schauspieldirektor” in the competition on the same evening, and the theme “Musica e Parole” occupied him throughout his life.

From Mozart comes the apt phrase about poetry being the “obedient daughter” of music. I quote from a letter dated 13 October 1781: “In an opera, poetry must be the obedient daughter of music. Why then do the French operas please everywhere, with all the misery as far as the book is concerned? Even in Paris, which I myself witnessed? Because music reigns there and one forgets everything about it.

Those who rejoice after this passage from the letter and believe that, based on it, one can also forget the text of Mozart’s operas, fail to realise that Mozart dealt very intensively with his libretti and also worked on them. He was anything but indifferent to the text; indeed, he was always concerned to merge the music with the feelings of his characters expressed in words as intensively as possible and to express even that which would not be equally perceptible in the words alone. When poetry is declared the “obedient daughter”, this means anything but that it can be ignored. Vocal music, music with words, wants to communicate everything that is contained in the words and word combinations and, in addition, to express that which cannot be grasped in words but which can be emotionally conveyed in music as a meta-language, which does not replace language but enhances its expression.

Dialogue between language and musical metalanguage

From this point of view, the word is at the beginning, and the word becomes the material that becomes even more comprehensible and even more immediately effective through musical invention and composition. Language and musical metalanguage combine in a wonderful dialogue. From the composers’ and lyricists’ point of view, anyone who only concentrates on the meta-language misses out on part of the miracle of mediation through vocal music.

Even Richard Wagner, who was his own librettist and thought a lot about words, sound and rhythm, and who gave the German language priority in this respect, had his operas performed in France and England in translated versions so that the audience could at least follow the meaning. For it is only through this sense that the music becomes comprehensible – even for Wagner. This form of understanding the meaning makes it easier for the audience to use the technology available today of making the translation visible in the form of subtitles.

But back to Bach, where things seem to be a little more complex. For the Bach lover might find a counter-argument for the central role played by the text over the music in the fact that Bach himself occasionally added secular and sacred texts to one and the same music. Reasons of time have occasionally been put forward for this multiple use of existing compositions and their recombination in a patchwork with new texts, for example in the Christmas Oratorio. Those who take the trouble to analyse the subtle connections between text and music more closely will find that in most cases various texts are also connected in terms of meaning. Analogies between human and divine love, for example, or between a love song and a lullaby, are striking because they were used again and again by Bach.

The top-heavy and text-obsessed Reformation banned music from church services in many places. Thanks be to Luther that he himself loved music and found it “not-necessary” in the best sense, that is, compensating for a need’ a deficit. Namely, the deficit that biblical texts could lose their effect on the individual without the forcefulness of music. Not only the needs, but also the tastes are different. I am thinking of well-educated people who have no use for classical music or poetry and who have not read a poem or sung a song since their school days. People who openly confess that they cannot afford to read fiction or a sophisticated magazine. These, too, are possibly cries from deep distress, from the time crunch to which the cantata poet alludes: “When my affliction holds as with chains / one misfortune to another. In this situation, one would like to wish that the second verse section “so will my salvation save me, that everything will suddenly fall from me” would also be given a chance.

At the beginning and at the end: the cry

I do not want to close this little reflection without speaking of the actual discovery that Martin Luther gave me with his dramatised rewriting of the 130th Psalm. While the psalmist “cried out from the depths” – “De profundis clamavi ad te Domine” (nothing of “crying out” and nothing of “distress”) – Luther actually cries out of deep distress. He is probably recalling the cry, the cry of distress, that Jesus uttered before his martyrdom, according to the testimony of the Gospels, before he bowed his head and passed away. At the end was the cry, but the cry was not the end.

But what was in the beginning? Was it really the word, the word in the sense of the logos, that is, something structured by consonants and vowels, fundamentally intelligible, rational and head- or larynx-born? No. Anyone who has ever experienced the individual beginning of life at birth knows: in the beginning was the cry, whether it is a cry of distress or the cry of liberation at the first breaths, or simply a primal form of emotion, may remain open. In any case, the word is not, and the cry as an expression is probably closer to music than to language. That is why I would like to add a small cadence or coda at the end. With it, I want to pay homage to my home canton of Appenzell. There are also songs without words, and not only since Mendelssohn. I mean the natural yodel, the “Zäuerli”. Its origins are not completely clear. They are certainly not purely rational. If you listen carefully, you can sense the religious and the magical, a melody that drives away the evil spirits of loneliness and depression. Both are part of the alpine dairyman’s life, which is not always just “luschtig”. Whenever things get too sentimental, the natural yodel makes itself heard again with a “whoop”, a cry of pleasure.

Albert Nef, brother of the renowned Basel musicologist Karl Nef, has set some of Julius Ammann’s Appenzell homesickness poems to music, as songs with words, but occasionally appended to them a yodel without words.

I quote:

Mi Ländli

Mi Ländli ischt e Schöpfigslied

hed herrgottschöni Strophe.

Fangt leesli meteme Jödeli aa.

You should know that it’s good for the people.

The melody grows and grows

one verse after the next

All over the hillside

The friendly song wanders.

At last there’s a whoop,

Heavenly happy,

You can stay and laugh.

The Lord God has let us use it

To make it on the Säntis.

My country is a song of creation

Has beautiful verses

Begins softly with a little yodel

As if it were only for children.

The melody grows and grows

One beautiful little verse after the other

From hill to hill then wanders

The friendly little song goes on.

At last comes a whoop,

A heavenly joy

It’s almost enough to make you cry or laugh

The Lord God himself has cast it out

In the middle of creating the Säntis.

So this is the Appenzell answer to the question of the relationship between words and music: in the beginning there was the yodel and in the end the cry, the whoop.

Literature

– Julius Ammann, Appezeller Spröch ond Liedli, complete edition of the poetry collections, Herisau, Trogen 1976

– Albert Schweitzer, Johann Sebastian Bach, Leipzig 1908

– Stefan Sonderegger, Appenzeller Sein und Bleiben, Niederteufen, Herisau 1979

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).