Jesu, nun sei gepreiset

BWV 041 // New Year's Day (Feast of the Circumcision)

(Jesus, be now exalted) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I–III, timpani, oboe I–III, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Ich will den Herrn loben allezeit; sein Lob soll immerdar in meinem Munde sein. Meine Seele soll sich rühmen des Herrn, dass es die Elenden hören und sich freuen. Preiset mit mir den Herrn und lasst uns miteinander seinen Namen erhöhen.

Ehe denn aber der Glaube kam, wurden wir unter dem Gesetz verwahrt und verschlossen auf den Glauben, der da sollte offenbart werden. Also ist das Gesetz unser Zuchtmeister gewesen auf Christum, dass wir durch den Glauben gerecht würden. Nun aber der Glaube gekommen ist, sind wir nicht mehr unter dem Zuchtmeister. Denn siehe auch unter Ratswechsel ihr seid alle Gottes Kinder durch den Glauben an Christum Jesum. Denn wie viel euer auf Christum getauft sind, die haben Christum angezogen. Hier ist kein Jude noch Grieche, hier ist kein Knecht noch Freier, hier ist kein Mann noch Weib; denn ihr seid allzumal einer in Christo Jesu. Seid ihr aber Christi, so seid ihr ja Abrahams Same und nach der Verheissung Erben.

Und da acht Tage um waren, dass das Kind beschnitten würde, da ward sein Name genannt Jesus, welcher genannt war von dem Engel, ehe denn er im Mutterleibe empfangen ward.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Stephanie Pfeffer, Simone Schwark, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Anne Bierwirth, Nanora Büttiker, Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Lea Pfister-Scherer

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Achim Glatz, Tiago Oliveira, Christian Rathgeber

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Claire Foltzer, Elisabeth Kohler, Olivia Schenkel, Petra Melicharek, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Magdalena Reisser

Violoncello piccolo

Martin Zeller

Violone

Guisella Massa

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Philipp Wagner, Clara Espinosa

Trumpet

Lukasz Gothszalk, Matthew Sadler, Alexander Samawicz

Timpani

Inez Ellmann

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Michael Maul, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Rudolf Osterwalder

Recording & editing

Recording date

29/04/2022

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

1 January 1725, Leipzig

Text

Johannes Herman (movements 1, 6); unknown source (movements 2–5)

In-depth analysis

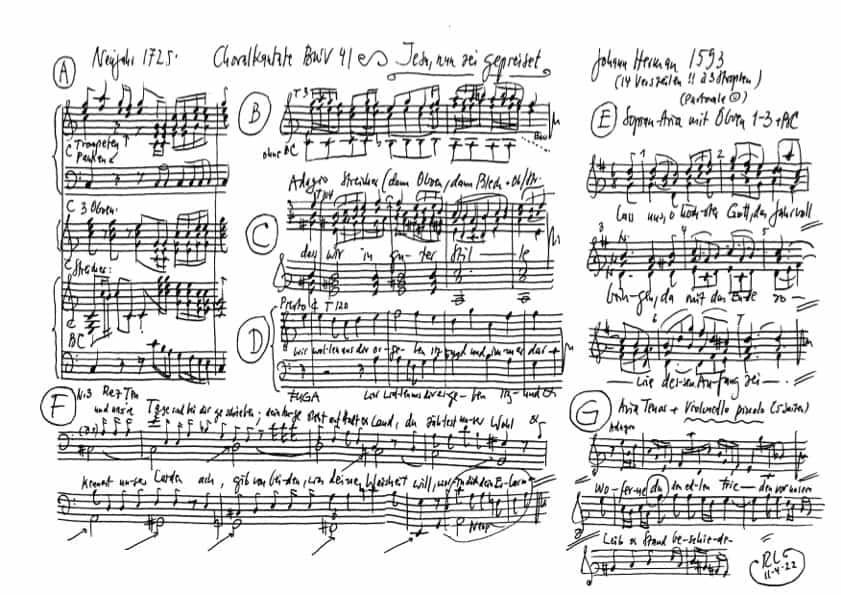

Composed for New Year’s Day, the cantata “Jesu, nun sei gepreiset” (Jesus, be now exalted, BWV 41) forms part of the chorale cantata cycle of 1724/25. Accordingly, the music is festive as befits a New Year’s celebration but, like all works in this cycle, also closely related to the designated Sunday hymn.

The introductory chorus poses Bach with an immediate challenge, as the fourteen-line text by Johann Hermann (1593) numbers among the longest verses the composer ever set. Bach approached the task by embedding the first eight lines – an augmented cantus firmus in the soprano underscored by free polyphony in the lower voices – in a three-choir string, brass and oboe framework characterised by lively syncopated motifs. The next section is marked by a stylistic shift that unites both textual interpretation and structural variety: indeed, the two adagio lines “Daß wir in guter Stille, das alt Jahr haben erfüllet” (That we in goodly stillness, the old year have completed) are not only decoupled from the brass-choir momentum of the previous section, but also emphasised in static, declamatory chords. The more action-oriented line “Wir wolln uns dir ergeben” (Ourselves we’d thee surrender) is then entrusted to a free motet setting with doubled strings and oboes, ere a return to the opening syncopated tutti writing, albeit in a new key, provides a framework for the last two lines and ensures a sparkling conclusion.

After this powerful opening display, the following soprano aria appears all the sweeter, as the ceremonial tones give way to a tone of introspective prayer and personal declaration. Ensconced in a lulling 6/8-metre and the pastoral timbre of three oboes, the vocal lines express the hopeful faith that the year just begun will continue to be protected by the Highest and that a grateful “hallelujah” will once again be sung at its conclusion.

The alto recitative expands on this line of argumentation, this time focusing on the life held in God’s hand, be it the individual or the whole community in “Stadt und Land” (town and land). Here, the lines beseeching the Highest, in his mercy, to allot each of us a bearable portion of both “Wohl und Leiden” (weal and sorrow) take on a strong philosophical undertone.

A traditional request inherent to a New Year’s celebration – thus far omitted by Bach and Hermann – is now lent particularly touching form in the tenor aria. Indeed, as in the current world, nothing could be more pressing than the “edle Friede” (noble concord) that here, in the accompanying cantilena of a high-tuned cello piccolo, takes on a tantalising charm. Through the equally fragile and noble musical gestures, the notion that the “selig machend Wort” (gracious, healing word) has the power to foster healing and a sense of community already here on Earth is raised to a happening that transcends the din of war.

That this existence nonetheless demands a steadfast, battle-ready will is called to mind in the bass recitative and its reference to the “Tag und Nacht lauernden Feind” (foe lurking day and night). In this setting, the words “Den Satan unter unsre Füße treten” (That Satan underneath our feet be trampled) – a line from the German litany that nods both to the earnest-archaic nature of New Year’s Day and to communal unity – interrupts the solo recital like a dissonant turba chorus from one of Bach’s Passions.

In the closing chorale, Bach’s eye for proportion and equivalence comes to the fore. By eschewing the obvious solution of a simple cantional setting in favour of a free-form movement with wind interludes and renewed use of changing tempi and gestures, Bach harks back to the compelling syncopations of the introductory movement and renders its structurally innovative form more plausible through this final repetition. And last but not least, the experienced teacher Bach also managed to incorporate one last message into this grand finale, with lines eleven and twelve of the setting impressively demonstrating that joyous singing has always worked best in a lively triple metre.

Libretto

1. Chor

Jesu, nun sei gepreiset

zu diesem neuen Jahr

für dein Güt, uns beweiset

in aller Not und Gefahr,

daß wir haben erlebet

die neu fröhliche Zeit,

die voller Gnaden schwebet

und ewger Seligkeit;

daß wir in guter Stille

das alt Jahr hab’n erfüllet.

Wir wollen uns dir ergeben

itzund und immerdar,

behüt Leib, Seel und Leben

hinfort durchs ganze Jahr!

2. Arie — Sopran

Laß uns, o höchster Gott, das Jahr vollbringen,

damit das Ende so wie dessen Anfang sei.

Es stehe deine Hand uns bei,

daß künftig bei des Jahres Schluß

wir bei des Segens Überfluß

wie itzt ein Halleluja singen.

3. Rezitativ — Alt

Ach! deine Hand, dein Segen muß allein

das A und O, der Anfang und das Ende sein.

Das Leben trägest du in deiner Hand,

und unsre Tage sind bei dir geschrieben;

dein Auge steht auf Stadt und Land;

du zählest unser Wohl und kennest unser Leiden,

ach! gib von beiden,

was deine Weisheit will,

worzu dich dein Erbarmen angetrieben.

4. Arie — Tenor

Woferne du den edlen Frieden

vor unsern Leib und Stand beschieden,

so laß der Seele doch dein selig machend Wort.

Wenn uns dies Heil begegnet,

so sind wir hier gesegnet

und Auserwählte dort!

5. Rezitativ — Bass und Chor

Doch weil der Feind bei Tag und Nacht

zu unserm Schaden wacht

und unsre Ruhe will verstören,

so wollest du, o Herre Gott, erhören,

wenn wir in heiliger Gemeine beten:

Den Satan unter unsre Füße treten.

So bleiben wir zu deinem Ruhm

dein auserwähltes Eigentum

und können auch nach Kreuz und Leiden

zur Herrlichkeit von hinnen scheiden.

6. Choral

Dein ist allein die Ehre,

dein ist allein der Ruhm;

Geduld im Kreuz uns lehre,

regier all unser Tun,

bis wir fröhlich abscheiden

ins ewig Himmelreich,

zu wahrem Fried und Freude,

den Heilgen Gottes gleich.

Indes machs mit uns allen

nach deinem Wohlgefallen:

solchs singet heut ohn Scherzen

die christgläubige Schar

und wünscht mit Mund und Herzen

ein seligs neues Jahr.

7. Choral

Selig sind, die aus Erbarmen

sich annehmen fremder Not,

sind mitleidig mit den Armen,

bitten treulich für sie Gott.

Die behülflich sind mit Rat,

auch, wo möglich, mit der Tat,

werden wieder Hülf empfangen

und Barmherzigkeit erlangen.

Rudolf Osterwalder

“Thou countest our weal and knowest our woe, Alas! Give of both”

Dear listeners

My first response when listening to the cantata was to notice the two “Achs” in the cantata text. How are they to be interpreted? One Ach of humility, one Ach of sorrow. The second Ach, “Ach! Give of both, weal and woe”, awakened a memory in me: as primary school pupils, we were asked in religion class to consider which “Our Father” petition impressed us the most. To the astonishment of the teacher, I decided on the petition: “Thy will be done”. (I had not known the cantata text…) Today, in view of the dramatic situation in the world, I feel provoked by the statement: “Give us from suffering.” Or does the “Alas” sound like a quiet resistance and protest, a lament? The good, but also the suffering are supposed to be driven by God’s “wisdom and mercy”, entirely in the sense of G. W. Leibniz’s theodicy. In today’s world, however, where suffering and violence are omnipresent, any romantic trivialisation of suffering is provocative, as Eduard Mörike, for example, put it in his poem:

“Lord! Send what you will, a love or a sorrow, I am amused that both spring from your hands.”

Despite my criticism of the approval of suffering, which for me is too uncritical, I am impressed by the piety which the cantata radiates. This against the background of the history of Saxony in the early eighteenth century. Plague and famine, the Northern War with many dead Saxons and still witch trials shook the countryside or were only just over. Life expectancy was 35 for men and 38 for women. Johann Sebastian Bach lost half of his children when they were barely born or still very young. Nevertheless, he wrote “Soli Deo Gloria”, to the glory of God, on many of his cantatas. Not only were the beautiful cantatas written against a background of deep piety; the magnificent Frauenkirche in Dresden was also planned and realised during the same period.

How is this acceptance of suffering to be interpreted? Is it an identification with the aggressor, a kind of Stockholm syndrome? The theologian Karl Rahner sees suffering in all its harshness: “There is infinitely manifold, horrific suffering in the history of mankind, which has a destructive effect, simply overwhelms man and cannot be integrated into a process of maturation and personal probation.” In addition, his pastoral advice: “Live in such a way that the suffering imposed on you and your environment does not destroy you in your ultimate attitude towards God into despair.” In relation to suffering, there is no sense of a “give of it”.

The word “despair” builds a bridge for me to my profession: psychiatrist and psychotherapist. Because I have been confronted with terrible suffering and pain of patients in my work, you may better understand my resistance to glorifying suffering. How am I supposed to explain to a traumatised mother who holds her dying child, who has fallen out of a window, in her hands and can only accompany it to its death, that this acute pain has a meaning? How am I supposed to be grateful for the suffering when a student runs out of exams and hangs himself? How am I to explain to the severely depressed patient that the despair, the emptiness, the powerlessness makes sense? Can I expect the desperate raped woman to see her crisis as an opportunity? For what should refugees be grateful for their suffering when they have seen children die in the hail of bombs, or the women had to leave their husbands behind in the war?

To this day, theodicy cannot answer the question of why God allows all this to happen. I follow Odo Marquart, who has dealt intensively with the subject and comes to the conclusion that it is not possible for a human being to answer the questions surrounding theodicy. The view of F. Nietzsche, who places God beyond good and evil, has a liberating effect.

At this point a differentiation is necessary: I deny meaning to acute suffering. However, there are also people who go through a positive development after overcoming a crisis; one could call this a collateral chance. In this way, positive developments, new value systems can emerge from a borderline experience. I am thinking of a manager who reorganised his life after a resuscitation and became involved only in charity work. His near-death experience was impressive: he felt safe, enveloped in a bright light which, to his astonishment, did not dazzle him. Since this experience, he was no longer afraid of dying, and even had a certain longing for what he had experienced, but without being suicidal. Literary history shows another example of a positive effect of crises: many authors have gained inspiration for their works through experiences of personal crises. Crises therefore do not always have to be negative. Developmental psychology shows that turbulence can be important, even necessary, for the maturation of the personality. In therapies, one often experiences that shocks in the treatment process can be quite fruitful and initiate a next step in development.

In therapies, the question of the cause of suffering and evil is less connected with theodicy than with the question of the meaning of life.

C. G. Jung says: “The religious question plays a role in every therapy. This always poses the crucial question to the therapist: What do you think about religion? C. G. Jung’s answer: “Life contains sense and nonsense; I have the fearful hope that sense will prevail. When patients asked me the question about the meaning of life, I usually answered: “You can deal with the question of meaning in different ways: Deeper reflection can end in brooding and despair. But it can also lead to wonder at the miracle of life and the cosmos.” I mean that every human being has a connection to transcendence in some way. What does transcendence mean? According to Karl Jaspers, it is “the ultimate infinite being which eludes any rational effort of thought or objectifying representation”. Depending on one’s socio-cultural background, God or something else can be referred to in this way. Karl Jaspers uses the word “cipher” as the language of transcendence. A cipher can be anything that paves the transcendental way. Since, according to the Bible, the direct way to God is through Jesus, he can be called the central cipher for Christians. Other keys to transcendence can be, among others, the magnificent music of J. S. Bach, mysticism or love. Even natural science can be a cipher if it leads to wonder. As Stephen Hawking says: “If there is a God, for me he would be the sum of all the laws of nature.” Werner Heisenberg’s statement is impressive: “The first drink from the cup of natural science makes one atheistic, but God waits at the bottom of the cup.” And, “Before matter there was symmetry.”

In the cantata, Satan is vehemently declared to be at war. Obviously, a distinction is made between evil and the suffering that God sends. “Evil” is a primordial word like love or God. The essence of such words cannot ultimately be grasped, at most guessed at. However, the effects and conditions of evil are dramatically perceptible.

Psychology knows various approaches to the subject of “evil”. Sigmund Freud, drawing on experiences from the First World War, postulated a death drive, which is juxtaposed to Eros. This “Thanatos” can gain the upper hand and cause evil destructive behaviour. The situation is particularly dangerous when lust is combined with aggression, as happens in rape. In the psychology of C. G. Jung, it is described that the human being has a predominantly unconscious shadow side which must be integrated into the self so that destructive behaviour can be avoided. According to Alfred Adler, frustration through devaluation plays a decisive role in the development of aggressive behaviour. Narcissism psychology assumes that in dangerous narcissists the transition from early childhood to secondary mature narcissism has not succeeded and thus empathy and any transcendental movement towards fellow human beings is impeded.

Hannah Arendt’s account of the Eichmann trial, in which she describes the “banality of evil”, is horrifying. Horrifying how cold and technically skilled killing can be. However, it is not only about war crimes, but also about the very banal everyday life. Every human being has his or her abysses, frustrations, envy, greed, lust for power, hatred and aggression.

The therapy strategies go in two directions: People should be empowered to defend themselves against violence, but they should also learn to deal with their own aggression in order to avoid harmful destructive behaviour. Empathy training and transcendental horizon broadening play a crucial role in this.

Does the Christian faith have a therapeutic benefit? Yes and no. For many people, a reasonable faith is a support, it gives them a meaning to life. Conversely, a rigid belief in a punishing God can damage development, especially in children. In severely depressed people, pathological feelings of guilt can be intensified. Patients with schizophrenia may incorporate religious content into their delusional system or feel threatened.

Let me conclude with an example from my practice that has become a cipher of transcendence for me and underlines the importance of empathy. A middle-aged woman came into treatment after having made several serious suicide attempts. A lifetime of frustrations and disappointments led repeatedly to despair and a sense of powerless emptiness. Despite my professionalism, I was infected by the mood and I felt that all my usual interventions were useless. So I had no choice but to admit my helplessness and powerlessness. To the patient I said: “At the moment I am infected by your emotional state and feel helpless like you. But perhaps it will be easier for you if the two of us remain in this tunnel and endure the difficult situation together.” Later on, after the crisis had passed, she told me the reason why she no longer wanted to die. She had realised that she had only one chance: the chance to participate in life with all the suffering and also happiness that it might bring.

The word “chance to participate” touched me deeply. Isn’t that the goal of every therapy? The patient has found the transcendental path, towards community, towards “communio”.

Enabling participation in the community. A community that is also prepared, as the cantata impressively shows, to take up the struggle with evil. The struggle with Daimon, the confounder who tries to divide society.

The cantata challenged me. An initial “Ach” of protest against a trivialisation of suffering has become an “Ach” of wonder at the primal reasons for human existence. The wonderful music has formed a meta-level in which faith, happiness and suffering are transcended, a cipher of transcendence.

There remains a mandate for all of us: let us expand our empathy and mindfulness in order to avoid evil. Let us resist lies, violence and violations of human rights. Let us help to ensure that all people, as the patient put it, have the chance to participate in life.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).