Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbats

BWV 042 // For the First Sunday after Easter

(That evening, though, of the very same Sabbath) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo.

That Easter would in time be celebrated as a triumph of life over death could hardly have been foreseen by Christ’s disciples. For them, Good Friday and Easter Sunday brought not joy, but immeasurable pain: a reeling confusion between dashed hopes and perseverance, combined with anxiety about the future and fear of religious reprisal. Precisely this moment is captured by cantata BWV 42: “The evening, though, of the very same Sabbath, the disciples assembled, and the doors had been fastened tightly for fear of the Jews”.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Anaïs Chen, Sylvia Gmür, Martin Korrodi, Olivia Schenkel, Livia Wiersich

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Luise Baumgartl, Meike Guedenhaupt

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Dr. Des. Barbara Bleisch

Recording & editing

Recording date

04/17/2009

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 3, 5, 6

Poet unknown

Text No. 4

Jacobus Fabricius, 1632

Text No. 7

Martin Luther 1528/29

Johann Walter 1566

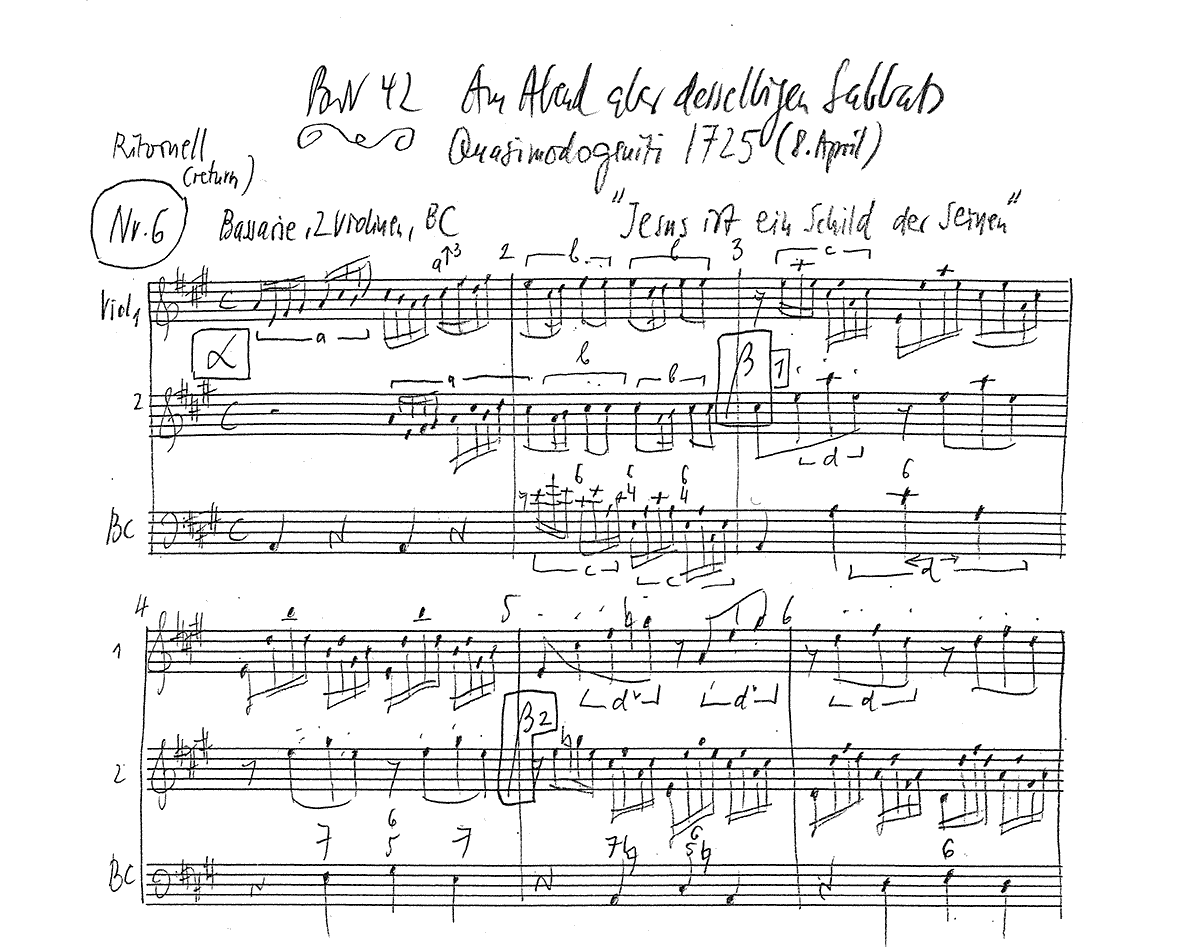

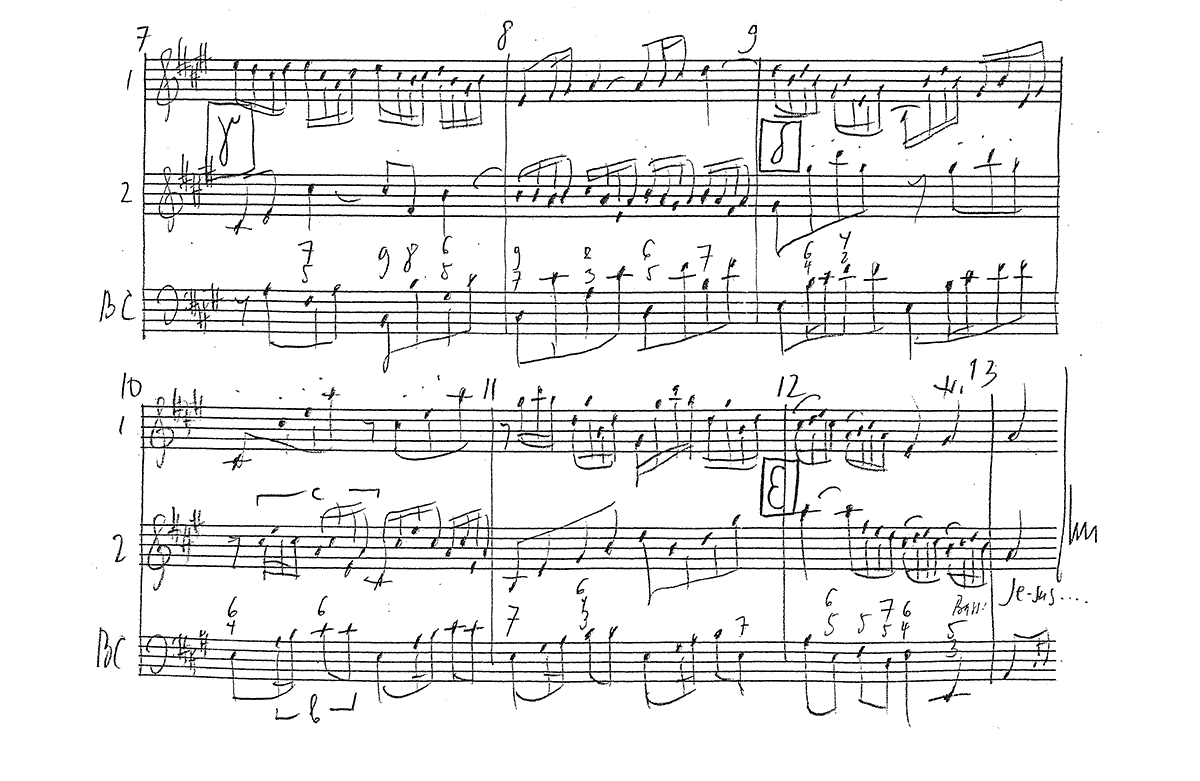

First performance

Quasimodogeniti,

8 April 1725

In-depth analysis

That Easter would in time be celebrated as a triumph of life over death could hardly have been foreseen by Christ’s disciples. For them, Good Friday and Easter Sunday brought not joy, but immeasurable pain: a reeling confusion between dashed hopes and perseverance, combined with anxiety about the future and fear of religious reprisal. Precisely this moment is captured by cantata BWV 42: “The evening, though, of the very same Sabbath, the disciples assembled, and the doors had been fastened tightly for fear of the Jews”. With this opening tenor recitative, the depth of the disciples disquiet is palpably underscored by the throbbing of the continuo. Before long, however, a wonder of music and text takes place; the resurrected himself comes and walks among the disciples, and the morose B minor transforms into a G major aria of heavenly breadth and beauty. Over a flowing basso continuo of tender, piano strings, two obbligato oboes eclipse one another with decorative figures and the throbbing bass semiquavers of the recitative give way to gentle, offbeat quavers from the bassoon. “Where two and three assembled are for Jesus’ precious name’s sake, there cometh Jesus in their midst, and speaks o’er them his Amen” – the entire ten-minute aria is a testimony of consolation, reassurance and peace.

The animated B section, by contrast, is more defensive in style, serving as a reminder that the disciples were not sectarians or conspirators, but rather a community appointed by the “Highest”. Here, something of the power of the Easter message that transcends all social classes and borders was transported to the hierarchical baroque society.

The chorale duet “Do not despair” then transforms the aria’s comforting words into a call to the “little flock” of believers to remain steadfast in the face of persecution. Here, the unflinching drive of the two-part continuo section carries the vocal parts through all attempts at destruction. That the story of the bible can serve as inspiration for all time is heard in the following recitative which culminates in a triumphant bass aria accompanied by two virtuosic violins: “Jesus shall now shield his people when them persecution strikes”.

The closing chorale commences somewhat surprisingly in F sharp minor, but then returns to the theme of peace and concludes with a prayer for a “peaceful and good life” under “good governance” – the great vision of Easter is over and the good citizens of Leipzig must return to overcoming the trials of everyday life. It remains only to say a few words on the opening A major sinfonia in da capo form. This introduction is generally assumed to derive from a previously existing concerto movement; in the context of the cantata, however, it takes on a different function and bears a striking similarity in key and vigour to the bass aria “Jesus shall now shield his people”. At the same time, it is hard not to interpret the tender cantabile episode at the beginning of the middle section as that moment in which Christ, on the path to Emmaus, opens the eyes of his disciples. In this sense, the cantata commences with a presentiment of its liberating conclusion.

Libretto

1. Sinfonia

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbats

da die Jünger versammlet

und die Türen verschlossen waren

aus Furcht für den Jüden,

kam Jesus und trat mitten ein.

3. Arie (Alt)

Wo zwei und drei versammlet sind

in Jesu teurem Namen,

da stellt sich Jesus mitten ein

und spricht darzu das Amen.

Denn was aus Lieb und Not geschicht,

das bricht des Höchsten Ordnung nicht.

4. Choral (Duett Sopran, Tenor)

Verzage nicht, o Häuflein klein,

obgleich die Feinde willens sein,

dich gänzlich zu verstören,

und suchen deinen Untergang,

davon dir wird recht angst und bang,

es wird nicht lange währen.

5. Rezitativ (Bass)

Man kann hiervon ein schön Exempel sehen

an dem, was zu Jerusalem geschehen;

denn da die Jünger sich versammlet hatten

im finstern Schatten,

aus Furcht für denen Jüden,

so trat mein Heiland mitten ein,

zum Zeugnis, dass er seiner Kirche Schutz

will sein.

Drum lasst die Feinde wüten!

6. Arie (Bass)

Jesus ist ein Schild der Seinen,

wenn sie die Verfolgung trifft.

Ihnen muss die Sonne scheinen

mit der güldnen Überschrift:

Jesus ist ein Schild der Seinen,

wenn sie die Verfolgung trifft.

7. Choral

Verleih uns Frieden gnädiglich,

Herr Gott, zu unsern Zeiten;

es ist doch ja kein ander nicht,

der für uns könnte streiten,

denn du, unser Gott, alleine.

Gib unsern Fürsten und aller Obrigkeit

Fried und gut Regiment,

dass wir unter ihnen

ein geruhig und stilles Leben führen mögen

in aller Gottseligkeit und Ehrbarkeit. Amen.

Barbara Bleisch

“Why being good alone is not enough”.

Or: How individual ethics and social ethics are mutually dependent.

Philosophers are famous for their love of talking a lot, for the fact that when the floor falls to them, they immediately come up with theses and antitheses, which can easily turn discussions into argumentative snowball fights. In this respect, I, as a representative of the philosophers’ guild, should get started straight away and lead you to a conclusion with accurate theses, the content of which may be hair-raising, but is argumentatively correct. The German aphorist Lichtenberg was unfortunately all too right when he is said to have once said that philosophy must be a woman for the sole reason that it is usually far-fetched.

But I don’t want to be a philosopher who conforms to this cliché. I prefer to do philosophy as a mindful way of thinking that carefully gropes its way to the truth and is constantly aware of the provisionality of its results. Above all, however, I delay my speech because whenever I hear Bach’s music sound, I am seized by the inner need to put my finger to my lips and by no means disturb the reverberation – even when the last note has long since faded away. For in the heart, in the soul, it resonates, this music. Not everything can be talked about, even the philosophers know that, and no one has expressed this more beautifully than Wittgenstein, who concludes his “Tractatus” with the words: “What one cannot talk about, one must remain silent about.

Now, of course, I am not appointed to sit back in the pew and remain silent. And you have presumably not come here to have a quarter of an hour of silence imposed on you, although I could very well understand if that was exactly what you were in the mood for and you would like to feel the carrying sounds of earlier fading away inside. But I have already talked this resonance to pieces, tattered it like a pile of pure hand-made paper, which now lies before us as a confused heap instead of white and well-ordered. I would now like to follow my words with order, so that at the end of this speech you will have a pile of sensibly arranged thoughts in front of you, which the musicians, thanks to Bach’s art, will reassemble into a sound edifice, the sublimity of which we can then acknowledge with attentive silence.

The internal and the public

Actually, the cantata “Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbats” (On the evening of the same Sabbath) is about exactly the two poles I have just outlined: the internal, the individual existence on the one hand – and the public, living together on the other. Or to put it a little differently: the cantata spans a bridge between individual ethics or personal reflection on the good on the one hand and social ethics or communal reflection on what is right on the other. Let me try to bring you a little closer to this arc of tension in the following.

In the first aria, the alto begins with those words from the Gospel of Matthew that have already been translated into countless settings:

“Where two and three are gathered

in Jesus’ dear name,

Jesus stands in the midst

and says the Amen to this.”

So, according to the text, being gathered in Jesus’ name, interacting with one another in his spirit, causes Jesus to place himself in the midst of this group of people. One could say that the divine comes to life where God’s will is being done. Now I am not a theologian, but a philosopher, so I am not concerned with the laws of God, but with those of morality. Translated into my way of thinking, this would mean: where people act in the spirit of ethics and where they are able to interpret this spirit correctly, that is where ethics manifest themselves, that is where the morally right thing happens. When people respect each other, one could say, the spirit of mutual respect or morality prevails. And treating each other with respect requires precisely the inner reflection on the laws of morality that we carry within us in the form of moral feelings such as indignation, disgust, bad conscience – but also compassion, affection and empathy. Unfortunately, we can always be mistaken about the interpretation of these feelings: For example, we sometimes fail to feel compassion when people in need live at a great distance from us, although they are just as in need of help as people in our immediate vicinity. Or we are outraged by a too generous neckline on the evening dress of the lady sitting next to us in the concert hall, which, however, does not seem to indicate a moral offence, but rather a different taste than ours. With such exceptions, our moral feelings are nevertheless quite good seismographs for morally sensitive areas to which we should at least pay special attention.

Ethics, however, can no more stop at this reflection on individual morality than can our cantata text. For the question of how we arrive at a world that bears the seal of approval “ethically correct” (or at least “ethically as correct as possible”, for it would not be a human world if it were morally perfect) – this question, then, is not exhausted by whether individual people act in the name of ethics. Rather, it requires the addition of a second perspective, which I meant when I spoke of two poles above: namely, the perspective of social ethics. In ethics, we must not only ask ourselves: “How should I act?”, but also: “How should we live together? What rules should we give ourselves?” Or, to put it more clearly: “What is a just society?”

This second dimension is also echoed in the cantata, in the second stanza of the final chorale:

“Give our princes and all the authorities

Peace and good rule,

that we among them

that we may lead a quiet and tranquil life

in all godliness and honourableness.”

By linking this passage with the image of the intimate group that comes together in the spirit of Jesus, Bach seems to want to tell us that it is not enough to let the good spirit work in one’s own actions and to trust that Jesus – or the good – will then appear of its own accord. Being good alone is obviously not enough. In addition, there is a need for just framework conditions and good governance, which ensure that we all have the same opportunities to lead a sufficiently good life and to pursue our goals in peace and security. In other words, we will not be able to lead a good life if we all act in the spirit of ethics, but do not at the same time think about just framework conditions, because not all ethical problems that confront us can be handled by individual actions, however well-intentioned. Rather, our life together needs to be regulated by just guidelines and limits – by “good governance” – within which we can shape our lives as we see fit.

Two perspectives that are mutually dependent Why exactly do we need these two poles, individual ethics and social ethics? There are many reasons for this. Let me outline two of them below:

The first reason is as trivial as it is bitterly serious: If we do not provide for a just distribution of basic goods and for the security of the members of our society, we will soon sink back into Hobbes’ state of nature and wage war of all against all. For as Brecht put it succinctly, “First comes food, then comes morality!” Without “good regiment”, even being together in a small circle, however noble its motives, will achieve little. Social justice is the basis of every functioning society, and only in a functioning society can ethics take its firm place. Admittedly, Aristotle is right when he said: “If citizens are friendly to one another, justice is not necessary” (“Nicomachean Ethics” VIII.1). In fact, morality would then suffice, the individual striving to treat each other with respect and to leave those goods that they lack and that we have in abundance. However, friendship does not exist on earth, or at least it does not always exist everywhere. That is why we need social framework conditions that put a stop to the state of nature.

But we need just framework conditions and social security not only because we are not so good that it would suffice to appeal to our conscience and call on each other to act virtuously. Secondly, we also need it because corresponding laws act like a moral division of labour. And sharing the work usually has three advantages: First, it is efficient because everyone can do the part they do best; second, it is fair because the institutional division of labour ensures that everyone has to do it and not just a few moral heroes; and third, it is relieving for the individual because he or she can delegate part of his or her responsibility to appropriate institutions. Imagine if we did not live in a welfare state, there would be no social assistance, no right to schooling and health insurance, no unemployment insurance. Presumably, if you knew that your neighbours did not have the money to send their children to school, you would hardly be able to sleep peacefully – let alone enjoy a meal in a restaurant with friends – if you became aware that these children were dying of easily treatable diseases because their parents lacked the money to visit a doctor. At the very least, you would have to subject your moral sensibility to a “dulling cure” in order to be able to live your life the way you do now – and the way you can do it now with the best conscience, because you are aware that you can delegate a large part of the moral attention upwards, i.e. to the state, while you are allowed to focus on your immediate area. Exactly the same in the cantata: In the small circle, God comes alive solely through the faith of those present, through being together in his name, while in the large circle, good government must ensure peace and order and a good life for all.

But if I have sung such praises of the organised moral division of labour and its supervision, does this not at the same time imply that we no longer need to worry at all about our individual responsibility? Isn’t it enough if we all behave according to the law and pay our taxes? Certainly, it is morally honourable if one or the other goes above and beyond for the common good or the environment – but is that really what is required of us? After all, there are people who are employed to clear away the free newspapers and empty drink bottles on the train, to drive old people for a walk in the nursing home or to push the shopping trolleys back from the car park to the Migros – so why shouldn’t I leave my rubbish and shopping trolley lying around or standing there? And why should I care about old people I don’t know? I could ease my conscience by saying that serious problems are solved institutionally in our society anyway. Fatherly state is there to help when there is a problem with living together in an orderly manner; we can apparently move our personal commitment from the street to the comfort of our own home or rented flat. And if there is no prohibition, a violation of the moral rule will probably not be so serious – will it?

Of course, it is not quite that simple. On the contrary, I am firmly convinced that we cannot possibly do without personal responsibility – just as we cannot do without just institutions that regulate our living together.

On the value of personal responsibility

To illustrate why I am saying this, let me take up a current example that is heating up many minds at the moment, namely littering, the leaving of rubbish lying around in public. Many consider it a moral problem (or even a scandal) that people simply leave their rubbish lying around when they leave a public place. The litter disfigures the environment (which is more of an aesthetic problem than a moral one), but it also affects others, because it is not very pleasant to spread out your picnic blanket in the midst of mountains of litter and risk cutting yourself on broken glass. Now, the sanctions of morality – contempt, spite, swearing at today’s so-called youth – seem to have little effect against the mountains of rubbish, quite apart from the fact that it is not very edifying to listen to these very reactions or to feel them surging within oneself. For this reason, legal steps are currently being considered or have already been taken in various Swiss cities in the form of fines for the so-called litterers. In this sense, we are increasingly acknowledging moral missteps with legal sanctions and forcing each other through corresponding laws to abide by rules whose normativity apparently no longer seems to work without the threat of punishment. Those who live in Zurich are familiar with the icons in the trams, which have given rise to much amusement, but also criticism: Under threat of punishment, there are prohibition boards showing stick figures sawing up seats, lathering up the person sitting next to them and the like. Whether this action should have served to amuse the passengers, I don’t know; but in my opinion it reflects above all a piece of zeitgeist, that rules are supposed to fix what the citizens no longer seem to be able to do on their own.

Not everyone, however, is enthusiastic about the idea of regulating by law what would actually have to do with good manners and lacks respect for the environment and fellow human beings. And I think scepticism is indeed in order at this point. It may well be correct in some cases to use legal sanctions to prevent undesirable behaviour – for example, when vital goods are threatened, as in the case of grass on roads, which has been increasingly sanctioned by law over the years. But delegating everything to the law and the state seems to me to be fundamentally wrong. For on the one hand, we then run the risk of undermining the freedom of our citizens – a good that a liberal society cannot undervalue. For example, making it increasingly difficult for smokers to choose to smoke, even if they do not force anyone to smoke passively, is an encroachment on people’s freedom for which I do not think there are sufficient grounds.

On the other hand, if everything is regulated with the help of the law, we are deprived of the possibility of acting on our own responsibility. However, personal responsibility has been and is written in capital letters in our society, and I think that is a good thing. Because personal responsibility makes us valuable citizens and takes us seriously as mature individuals – even if we sometimes do not appreciate our maturity. Immanuel Kant already knew that it is sometimes more comfortable to do without one’s own maturity. I quote: “If I have a book that has understanding for me, a pastor who has a conscience for me, a doctor who judges diet for me, and so on, I need not trouble myself.” (Answering the question: what is enlightenment? 1784.) But doing the right thing because the law wants it is sometimes simply the wrong motive. If one day our children no longer throw litter on the ground because otherwise they will be fined, it seems to me that something essential has been lost: namely respect for others – and respect for nature. It is only because of this respect that litter belongs in the rubbish bin and not on the grass or on the pavement, not because otherwise there is a threat of punishment.

We have to hope for “good regiment” and work on it together – but this hope and work are not enough. In addition, it takes all of us to want and strive to be active in the spirit of ethics and to practise respectful interaction with each other and with our environment.

At the same time, it is also not enough if each and every one strives to be good for themselves alone or in the circle of their loved ones. For today we live in a time of great interdependence. In today’s age, no one can take account of its global interconnectedness on his or her own. Instead, we need to work on just institutions, on social ethics, in order to shape world society – or more pathetically: humanity – justly and to relieve each and every individual of the burden of great suffering or of witnessing it.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).