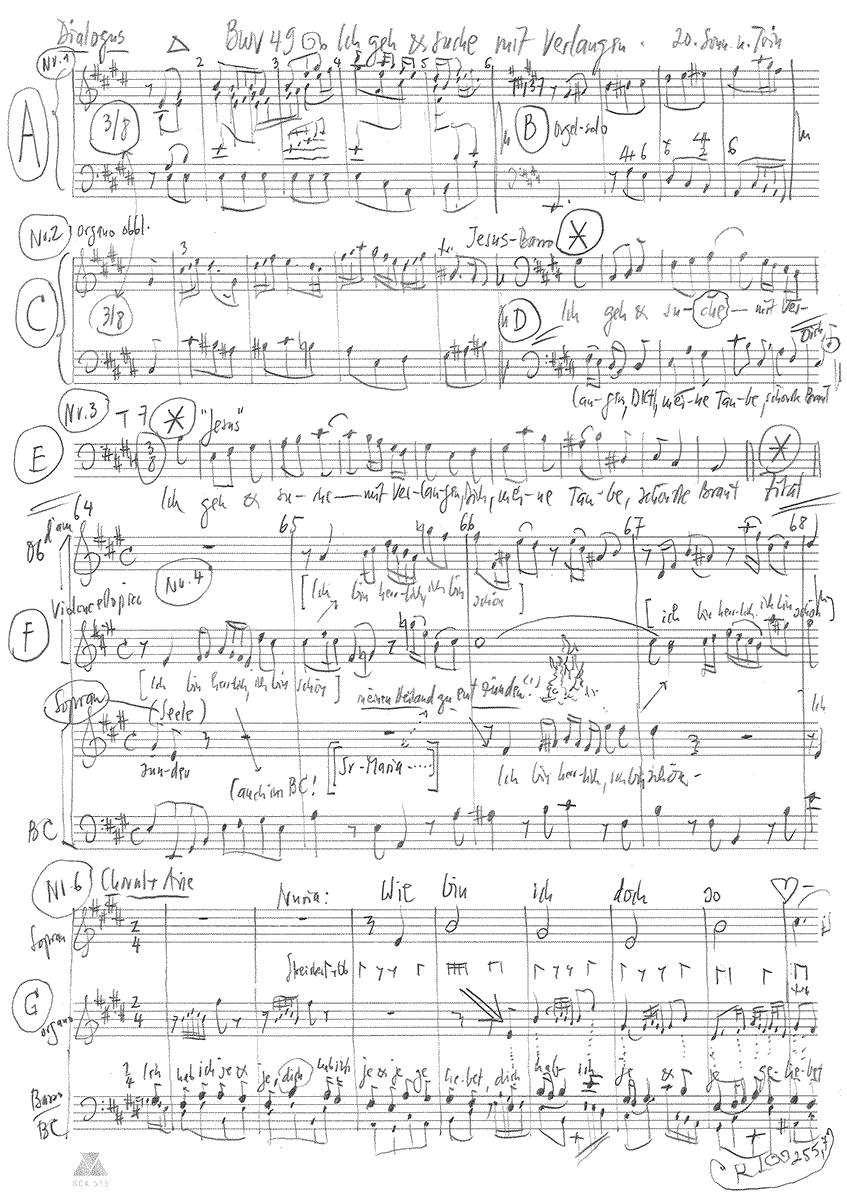

Ich geh und suche mit Verlangen

BWV 049 // For the Twentieth Sunday after Trinity

(I go and search for thee with longing) for soprano and bass, oboe d’amore, violoncello piccolo, organ, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Claire Foltzer, Olivia Schenkel, Marita Seeger, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Martina Zimmermann

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violoncello piccolo

Martin Zeller

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe d’amore

Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organo Obbligato

Jörg Andreas Bötticher

Harpsichord

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Karin Scheiber

Recording & editing

Recording date

27.10.2017

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Author unknown

First performance

Twentieth Sunday after Trinity,

3 November 1726

In-depth analysis

First performed on the Twentieth Sunday after Trinity in 1726, BWV 49 is one of the few cantatas that Bach lent a distinctive character and momentum by including an obbligato organ part. The addition of an oboe d’amore, then, is equally a nod to the libretto on the Song of Solomon and a choice that augments the registers of the organ – itself a quasi-wind instrument.

Bach puts the potential of the solo keyboard instrument straight to work in the introductory sinfonia, a setting based on an earlier work that he later used again as the final movement of his harpsichord concerto BWV 1053. Set in a sparkling E major with a lively waltz of ascending triads, the oboes, doubled by strings, dance in joyous anticipation of the royal wedding feast described in the Sunday gospel. The confident organ figures, meanwhile, impart a distinctly cheerful character – as though Bach, the pious jazz pianist, wanted to prove that praising God and total coolness can go hand in hand.

In the bass aria, too, the organ takes centre stage: while the left hand plays a continuo line, the right features circling figures that evoke the longing search described by the vocalist in the role of Jesus. In the alternating passages of vocal questions and attentive instrumental responses, the calls of the Saviour are charged with a scenic presence that will resonate differently with each individual listener.

Set to a shimmering string accompaniment, the following recitative opens the actual “dialogue”, the historical form named in the work’s title. Jesus, sung by the bass soloist, links the invitation to the wedding table with the revelation of his identity as the bridegroom of the Soul. In this setting, there is a poignant immediacy to the bride’s joyous disbelief at her role as the chosen one and to the bliss of the protagonists as they draw closer in an everfreer duet.

Bach sustains this sensitive realism throughout the soprano aria. Upon reflection, the bride (the Soul) understands Jesus’ wooing as an all-encompassing affirmation of her very being: she is “herrlich und schön” (glorious and fair) because she is loved – a liberating realisation that, thanks to the distinct timbral strands of her wedding robe spun by the violoncello piccolo und oboe d’amore, appears far more credible than the Biedermeier-era cliches at the heart of Robert Schumann’s 19th century Lieder cycle “Frauenliebe und -leben” (A Woman’s Life and Love), a work with a similarly structured text. In this aria, by contrast, the common Bach-era notion of Jesus as a courtly lover loses all overtones of pietistic intellectualism and becomes the origin of a life-affirming sensuality – not the smallest gift that Martin Luther, the former monk who rocked the foundations of abbeys and dismantled notions of bodily shame, gave to his church. That the upper instrumental voices and soprano part are syncopated and, as such, enter “too early” lends an impatient charm to this setting’s justified celebration of the self. It calls to mind the image of a young woman, perhaps Bach’s Anna Magdalena, twirling before a mirror in pride at her latest conquest, even if the middle section is given to a more sacred interpretation (“seines Heils Gerechtigkeit ist mein Schmuck und Ehrenkleid” – His salvations’ righteousness is my cloak of honour bright).

The references to the lovers’ rendezvous in heaven are reinforced in the following recitative. Here, the wedding feast has become the “Erlösungsmahl” (meal of salvation) that the Soul has earned through her decision to devote herself to Christ. Rarely has a profession of faith sounded both so tender and resolute as her declaration of “Hier komm ich, Jesu, lass mich ein” (Here I come, Jesus, let me in); when the Saviour, more in the role of a spiritual father, then responds with the promise of a crown of life that overcomes death, the cantata reaches its thematic conclusion.

Nevertheless, Bach and his librettist Birkmann still have a dazzling encore in store that returns the organ to the spotlight. Set in a dance-like 2⁄4-metre and accompanied by light orchestral chords, the aria and chorale features an upper part brimming with celebratory pride and shimmering ecstasy. When the Saviour states in reference to the Old Testament prophecy, “Ich hab dich je und je geliebet” (Thee have I loved with love eternal), he is joined by the soprano presentation of the chorale verse “Wie bin ich doch so herzlich froh” (How am I now so truly glad) – and Philipp Nicolai’s somewhat shopworn “Morgenstern” (morning star) hymn attains the end-of-days rapture that it always intended to convey.

In studying the Song of Solomon, generations of theologians and philosophers have struggled to translate sensual desire into divine spirituality without relinquishing its body-and-soul captivating essence. The master composer Bach, however, experienced in love and life, effortlessly achieves just that in this “Concerto für Organo amoroso”, conjuring music that entices the listener to join in both the cooing “Amen” of the soprano and the trusting “Ich komme bald” (I’m coming soon) of the bass. And why shouldn’t we just sing along?

Libretto

1. Sinfonia

2. Arie (Bass)

Ich geh und suche mit Verlangen

dich, meine Taube, schönste Braut.

Sag an, wo bist du hingegangen,

daß dich mein Auge nicht mehr schaut?

3. Rezitativ (Duett Sopran, Bass)

Bass

Mein Mahl ist zubereit’

und meine Hochzeittafel fertig,

nur meine Braut ist noch nicht gegenwärtig.

Sopran

Mein Jesu redt von mir;

o Stimme, welche

mich erfreut!

Bass

Ich geh und suche mit Verlangen

dich, meine Taube, schönste Braut.

Sopran

Mein Bräutigam, ich falle dir zu Füßen.

Sopran, Bass

Komm, Schönste, komm und laß dich küssen,

Bass

du sollst mein fettes Mahl genießen

Sopran

laß mich dein fettes Mahl genießen

Bass

Komm, liebe Braut, und eile nun,

Sopran

Mein Bräutigam, ich eile nun,

Sopran, Bass

die Hochzeitskleider anzutun.

4. Arie (Sopran)

Ich bin herrlich, ich bin schön,

meinen Heiland zu entzünden.

Seines Heils Gerechtigkeit

ist mein Schmuck und Ehrenkleid;

und damit will ich bestehn,

wenn ich werd in Himmel gehn.

5. Rezitativ (Duett Sopran, Bass)

Sopran

Mein Glaube hat mich selbst so angezogen.

Bass

So bleibt mein Herze dir gewogen,

so will ich mich mit dir

in Ewigkeit vertrauen und verloben.

Sopran

Wie wohl ist mir!

Der Himmel ist mir aufgehoben,

die Majestät ruft selbst und sendet ihre Knechte,

daß das gefallene Geschlechte

im Himmelssaal

bei dem Erlösungsmahl

zu Gaste möge sein.

Hier komm ich, Jesu, laß mich ein!

Bass

Sei bis im Tod getreu,

so leg ich dir die Lebenskrone bei.

6. Arie mit Choral (Deutt Sopran, Bass)

Dich hab ich je und je geliebet,

Wie bin ich doch so herzlich froh,

Dass mein Schatz ist das A und O,

Der Anfang und das Ende.

Und darum zieh ich dich zu mir.

Er wird mich doch zu seinem Preis

Aufnehmen in das Paradeis;

Des klopf ich in die Hände.

Ich komme bald,

Amen! Amen!

Ich stehe vor der Tür,

Komm, du schöne Freudenkrone, bleib nicht lange!

Mach auf, mein Aufenthalt!

Deiner wart ich mit Verlangen.

Dich hab ich je und je geliebet,

Und darum zieh ich dich zu mir.

Karin Scheiber

Mysticism and Eroticism

The cantata “Ich geh und suche mit Verlangen” (BWV 49) refrains from discovering the love of God in erotic love – which could be suggested by the mystical experience. Instead, following the tradition of bridal mysticism, it takes the path of an allegorical interpretation.

The cantata “Ich geh und suche mit Verlangen” (BWV 49) requires us to engage with the tradition of bridal mysticism. In the mystical experience, the sharp boundary between God and me, between Creator and creation, is abolished, not the asymmetry, the distance, the difference is felt, but the connection, the union, the all-unity. This cannot be theologically and dogmatically defined, and it cannot be practically defined in life either. It remains a momentary experience, never becomes a state or a habit. But as a moment, an intense, filled moment, it stands outside of time, is what we can call “eternity” with the evangelist John or with Søren Kierkegaard.

To the institutional guardians of the right faith, mysticism was and is monstrous in all religions and at all times. Its individualism, the immediacy of its access to the divine, its affectivity and non-domesticability arouse suspicion in those who like to know and prescribe to others what is right and what is wrong.

In bridal mysticism, the mystical experience finds its image in the loving union between bride and groom. On the one hand, the text of the cantata is clearly in this tradition, but at the same time it has its own characteristic features. We have the typical bridal mysticism of bride and groom, with the roles assigned to the human soul and Jesus Christ; there is talk of betrothal and marriage, loving and kissing; we find various allusions to the Song of Songs, the biblical source of inspiration for Christian bridal mysticism par excellence. Compared to other texts of bridal mysticism, however, this one is remarkably moderate as far as erotic metaphors are concerned: the bride and groom do not get any further than kissing, the end and goal is the wedding feast, not the wedding night. In addition, we find dogmatic turns of phrase that disturb and break the poetry of the whole, for example when it says “His righteousness is my ornament and garment of honour” or “My faith has so clothed me”, or when it speaks of the “fallen generation”. This smells – not to say stinks – of church censorship being satisfied here by omitting what might be offensive in their eyes or cushioning it with allusions to the doctrinal system of old Protestant orthodoxy.

The effort to tame the impetuous power of the erotic speech of God – an erotic theo-logy – can also be found in a somewhat different form in the other great currents of Christianity. For Bernard, the mystic and crusade preacher from the Cistercian monastery in Clairvaux, the union of bride and groom does not end with the kiss, but he never tires of explicitly allegorising it so that no one gets the wrong idea: It is not a matter of man and woman, but of the Word and the soul, not of sensual feeling, for this is mute and deaf in intercourse with God, the kiss is the Holy Spirit, the lips of the bride are will and understanding, her conception is the infusion of grace, the child she gives birth to is saved souls and spiritual knowledge.

In the Eastern Church, on the other hand, Gregory of Nyssa in the fourth century can describe in his interpretation of the Song of Songs “in highly figurative and eroticised language the ascent of the soul into intimacy with the life of the Trinity” (Coakley), but this is not connected with a theological recognition or even valorisation of human sexuality, rather the erotically coloured vision of God is entirely in the service of sublimating human inclinations. Thus Gregory writes: “We are to learn from this that the soul, fixing its gaze on the inaccessible beauty of divine nature, must love it as much as a body can incline to the familiar and kindred, while it transforms sensual passion into the spiritually unsuffering, and thus, suffused by the fire which the Lord came to cast upon the earth, stifles all bodily inclinations, so that only the spirit in us lives in passion of love for the only Spirit.” Today, there is widespread agreement to see in the biblical Song of Songs a secular love song that sings of erotic love between a man and a woman. The tradition of bridal mysticism interprets it spiritually as an allegory for the love between God and man. The constant emphasis on the allegorical character misses the chance to discover the divine in human, earthly, erotic love. When it says in the First Epistle of John “God is love”, the Greek word αγαπη (agape) refers to charitable neighbourly love. But is the love of God only present in this dimension of love? When two people surrender to the mutual erotic attraction, experience the power of desire and being desired (“I go and seek with desire”), of touching and being touched in body and soul, then they can experience that the so-called climax is not the peak of activity, of control, of performance, of mastering oneself and others, but just the opposite: ecstasy, stepping out of oneself, the radical self-exposure to the other, the unreserved letting go. The latter would rather suggest the metaphor of the nadir. The fact that we nevertheless speak of climax instead of nadir preserves something of the paradoxical character of erotic love. But precisely in this it has much in common with the mystical experience of God, which sees the greatest gain in losing oneself.

This is not an allegory, but a common trait of the mystically experienced love of God and erotic love. I am not saying this in order to make religion acceptable again through the back door in our sex-obsessed times – because what kind of salon would that be to enter through the back door? Most likely a massage parlour. No, I am more concerned with a rethinking of religion as well as erotic love.

A striking feature of our time is the huge gap between the image of sexuality conveyed in advertising, films, music, magazines and self-representations by stars and starlets on the one hand, and scientific studies and surveys of real-life love lives on the other. There is certainly more than one plausible explanation for this gap. However, one seems to me to be of particular interest in our context. The image conveyed in public turns erotic love into high-performance sexual sport. The fact that this does not lead to a deepening and intensification of love life need not surprise us once we have realised the paradoxical character of the climax as a low point. In the placativeness of climaxing, in the performance-relatedness and self-fixation of today’s sex talk, this is systematically obscured and faded out.

How different the Song of Songs is! Here it is not one climax after the next. It speaks of seeking and finding, of losing again and seeking again, of the warmth and pain of the ardour of desire. With the beauty of the language, the words, the evoked images, it seeks to do justice to the beauty of the beloved and love, while our contemporary speech often seems to have only the alternative “vulgar or technical” open to it.

The different allegorising interpretations, and especially the variant of the cantata text that tends towards prudishness and dogmatism, reveal a fear towards the irrepressible power of the erotic. Or is it a fear of the unbridled power of the love of God, in whatever of its many guises? When we look at the religious landscape in our latitudes today, can we not discover remarkable parallels with the sexual landscape? A deplorable lull in the established beds on the one hand, and a self-promotion bordering on pornography and prostitution on the other?

Underlying both is the same desire for domestication, the fear of letting oneself go, of surrendering, of letting oneself be taken over by the power of God, of experiencing the nadir of one’s own performance and control as the pinnacle of divine love.

I am not propagating an equation of erotic love and the love of God. Eros is not a god, we do not need to pay homage to him. But we do not need to demonise it either. Erotic love is susceptible to disturbance, it can be abused, distorted and perverted, certainly. But just as certainly this applies not only to erotic love, but to all loving, including neighbourly love, and in general everything that people come into contact with.

When two people give themselves to each other in deep mutual love with skin and hair and experience a power that is more than the power of the I or the you, and also more than the power of the I and the you, and can let themselves fall in it and experience themselves carried, this is not only an image or an allegory for the love of God. God is not afraid to show us his love in human form, exposing himself to the possibility of profound misunderstandings – that is one of the basic statements of the Christian faith. Of course, one may read the Song of Songs allegorically. If I read it theologically, then as an invitation to discover the love of God in all human loving, in other words: its incarnation.

Literature

– Sarah Coakley: “Persons” in the “Social” Doctrine of the Trinity. Analytical Discussion Today and the “Cappadocian” Theology, in: This: Power and Submission. Spiritualität von Frauen zwischen Hingabe und Unterdrückung, translated from English by Geiko Müller-Fahrenholz, Gütersloh 2007, pp. 147-169, here p. 166.

– Peter Dinzelbacher: Bernhard von Clairvaux. Leben und Werk des berühmten Zisterziensers, 2nd ed., Darmstadt 2012, p. 181.

– Gregory of Nyssa: The Sealed Source. Auslegung des Hohen Liedes, ed. by Hans Urs von Balthasar, 2nd ed., Translated and introduced in abridgement by Hans Urs von Balthasar, Einsiedeln 1954, p. 34 (my ed.).

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).