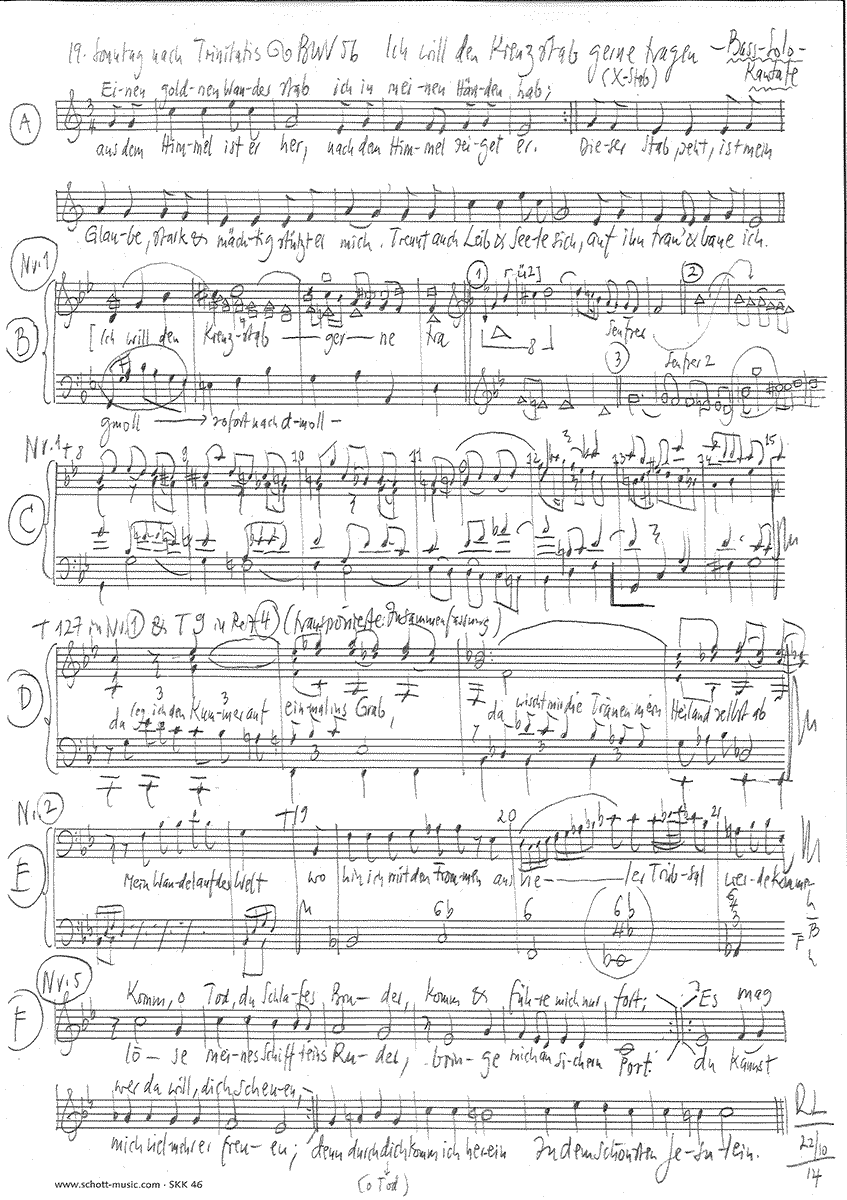

Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen

BWV 056 // For the Nineteenth Sunday after Trinity

(I will the cross-staff gladly carry) for bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, taille, violoncello, strings and basso continuo.

The cantata “I will the cross-staff gladly carry” was written for the 19th Sunday after Trinity in 1726. Thanks to recent scholarship, the long unknown librettist has been identified as Christoph Birkmann (1703–1771), a theologian from Nuremberg. Birkmann belonged to Bach’s circle of students during his studies in Leipzig and apparently wrote numerous libretti of striking eloquence for the Thomascantor.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Soloists

Bass

Klaus Mertens

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres

Alto

Alexandra Rawohl

Tenor

Clemens Flämig

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Eva Borhi, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Sarah Krone, Christoph Riedo

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Thomas Meraner

Oboe da caccia

Philipp Wagner

Taille

Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Oswald Oelz

Recording & editing

Recording date

10/24/2014

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–4

Poet unknown

Text No. 5

Johann Franck, 1653

First performance

Ninteenth Sunday after Trinity,

27 October 1726

In-depth analysis

The introductory aria, with a head motive that is propelled by the energy of the continuo and culminates in descending sighs, makes an indelible impression. The orchestral accompaniment – at once lugubrious yet light – envelops and carries the vocalist, who, by repeating each section of text before advancing to the next passage, feels his way towards an acceptance of suffering and the acknowledgement of human mortality. Here, Bach’s interpretation of the words “the cross leadeth me”, in which he reverses the descending sighs of the opening passage to create an ascending line, is just as masterly as the sudden musical release that is linked to the source of all “troubles” from “God’s beloved hand”. This struggle between the hope of salvation and the experience of pain is eventually resolved in a triplet passage by the bass soloist who expresses hope that the saviour himself will soon wipe away the very tears that Bach so heartrendingly depicts in the closing phrase.

The recitative, a vivid account of a wave-tossed, yet protected “voyage at sea”, belongs to Bach’s most sensitive interpretations; with its cello part of rolling broken chords, the maritime imagery of the librettist is ideally rendered. This is particularly apparent in the conclusion, where Bach captures the end of the journey in a moment of musical deceleration that enables the soloist to confidently step ashore and enter his heavenly city. Nonetheless, a last reminder of the “deepest sadness” that has been overcome is evoked by a final running figure that concludes on a dissonant note.

This is followed in aria number three by a peaceful meditation on the release from all troubles that Bach scores as a trio for continuo, oboe, and bass vocalist. Set in ternary form, the underlying mood (particularly in the A section) is not one of triumphant rejoicing at the resurrection, but relieved gratitude and joyous anticipation; here, life is seen as a burdensome “yoke”, a depiction that lends insight into the world view of baroque times. In the robust middle section, death – in contrast to all human perception – is not portrayed as a loss of all strength and power, but is celebrated as an eagle-like ascension into a higher state of being.

The recitative “I stand here ready and prepared” is a rich accompagnato setting that adopts a celebratory tone to announce the determination to leave all earthly misery behind in favour of the heavenly inheritance. In this movement, the composer returns to the triplet figure of the introductory aria to create an arc of tension that is effective in its semantics and formal features, while also lending the short orchestral postlude the impression of a recapitulation of the bygone life.

“Come, O death, of sleep the brother” – with this verse from Johann Franck’s hymn “Du, o schönes Weltgebäude” (1653), the cantata closes with a chorale in C minor that, despite its simplicity, belongs to Bach’s most famous settings; indeed, beyond the world of music, its theme has been adapted in art and literature. Due to the low register of the setting and the glorious phrase modulations, the singing is imbued with a melancholy peace and strength that serves to heighten the brilliant, open sound of the closing chord: here the faithful are united with Jesus, a saviour who is both fatherly friend and babe in the manger.

Libretto

1. Arie

Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen,

er kömmt von Gottes lieber Hand.

Der führet mich nach meinen Plagen

zu Gott in das gelobte Land.

Da leg ich den Kummer auf einmal ins Grab,

da wischt mir die Tränen mein Heiland selbst ab.

2. Rezitativ

Mein Wandel auf der Welt

ist einer Schifffahrt gleich:

Betrübnis, Kreuz und Not

sind Wellen, welche mich bedecken

und auf den Tod

mich täglich schrecken;

mein Anker aber, der mich hält,

ist die Barmherzigkeit,

womit mein Gott mich oft erfreut.

Der rufet so zu mir:

Ich bin bei dir,

ich will dich nicht verlassen noch versäumen!

Und wenn das wütenvolle Schäumen

sein Ende hat,

so tret ich aus dem Schiff in meine Stadt,

die ist das Himmelreich,

wohin ich mit den Frommen

aus vieler Trübsal werde kommen.

3. Arie

Endlich, endlich wird mein Joch

wieder von mir weichen müssen.

Da krieg ich in dem Herren Kraft,

da hab ich Adlers Eigenschaft,

da fahr ich auf von dieser Erden

und laufe, sonder matt zu werden.

O gescheh es heute noch!

4. Rezitativ

Ich stehe fertig und bereit,

das Erbe meiner Seligkeit

mit Sehnen und Verlangen

von Jesus Händen zu empfangen.

Wie wohl wird mir geschehn,

wenn ich den Port der Ruhe werde sehn:

Da leg ich den Kummer auf einmal ins Grab,

da wischt mir die Tränen mein Heiland selbst ab.

5. Choral

Komm, o Tod, du Schlafes Bruder,

komm und führe mich nur fort;

löse meines Schiffleins Ruder,

bringe mich an sichern Port.

Es mag, wer da will, dich scheuen,

du kannst mich vielmehr erfreuen;

denn durch dich komm ich herein

zu dem schönsten Jesulein.

Oswald Oelz

Fulfilling suffering and redeeming death

At first glance, the text of the unknown poet of the cantata “I will gladly bear the staff of the cross” seems outdated; it contradicts the spirit of the times – at least that which seems to prevail in our part of the world, which is still anointed by happiness. The healing of gout-ridden people described in the corresponding Sunday Gospel from Matthew 9 does not require divine miracles today, but a few pills from Basel.

In fact, two aspects of the text of the cantata “I will gladly carry the cross staff” have long appealed to me in particular: On the one hand, the almost joyful willingness to bear one’s cross, the pain and hardship of life. On the other hand, the serenity and calmness to accept Schlafes Bruder in the confidence that he will end up in a safe haven.

The willingness to endure the hardships of life, that is, to suffer, is not modern. The toil of physical labour has been taken over to a large extent by machines. Climbing stairs is no longer necessary since there are escalators and lifts, picking up apples and pears is not worth it, they rot on the ground. Headaches, backaches or monthly pains can be treated, and for the unbearable bone pain of a carcinoma there is surgery, radiation, palliative chemotherapy and finally morphine.

Mental pain, depression and even grief and loss can also be alleviated, be it with the help of serotonin antagonists or through care teams. How often we hear or read in the media after major accidents the stereotype: “the relatives/survivors of the accident are receiving psychological care”.

We live in an ideal world with little pain, the valley of suffering has been crossed, Florestan stands in the sunlight again and holds his beloved in his arms. But in some of us there is something that does not cooperate. Those born with the silver spoon in their mouths populate the psychotherapists’ surgeries, become addicted to all kinds of drugs, let themselves be whipped and, when things get really bad, commit suicide. Others don the robes of monks, internalise themselves through fasting cures, yoga or climbing the Matterhorn and eight-thousanders. Some have realised that what falls too easily into the lap is not valuable and is not appreciated. What is truly valuable must be suffered. Goethe wrote “suffering taught me much” and in Kierkegaard we learn that truth only triumphs through suffering. From Schopenhauer and Nietzsche we learn that the degree and ability to suffer is the measure of individual rank. And Joseph Beuys declared: “It would be a great question who enriches the world more: the active or those who suffer? I have always decided: the suffering. The active may achieve human things for the world. But a sick child who lies in bed all his life and can do nothing at all suffers and through his suffering fills the world with Christian substance.”

Christian substance as Christ understood it.

In the simple example of mountain climbing, which is obvious to me, this is quite obvious: those who can torment themselves higher in the game of suffering, unimpressed by pain and shortness of breath, finally reach their personal end point. That’s why this cantata text ran through my head as an eternally circling message a few years ago when I was climbing a big wall in Oman, and it never let me go. I had the cross staff in the form of a heavy rucksack on my back, the singer assuring my head that this burden came “from God’s dear hand”. When we finally reached the summit, our harbour, after two days, dehydrated and with bloody hands, we were happy as seldom before.

It is no different with the marathon run: from kilometre thirty onwards, the way of the cross begins. Feet, knees, hips and back ache. The title of another Bach cantata runs through your head: “Ich habe genung” (BWV 82). The running and the agony are completely pointless and yet have to be endured. At the end of the journey, the promised land, the kingdom of heaven, awaits us, no longer having to run. But how content we are in this kingdom of heaven, and how long we can endure it there, is another question. I have my doubts whether the ship will stay in port for long.

Ultimate suffering is death, finitude

The second theme of the cantata “Ich will den Kreuzstab gern tragen”, which is important to me, is the final chorale written by Johann Franck, “Komm, o Tod, du Schlafes Bruder”, i.e. the joyful expectation of the hereafter, the most beautiful description of the Ars Moriendi. Whenever I hear this chorale, I have to think of the Bach cantata “Wer weiß, wie nahe mir mein Ende” (BWV 27) with the aria “Willkommen, will ich sagen,/wenn der Tod ans Bette tritt”. Even in our secular times, when everything has to be experienced and mastered in a short span of time, death remains the true play director of life. Against this, an already primarily hopeless battle is being waged with fitness programmes, renunciation of butter, cholesterol-lowering drugs and chemicals. A lot of money is spent on the slightest extension of time, built-in defibrillators are supposed to prevent sudden cardiac death, because today life is the highest of goods – in contrast to Schiller’s opinion that it is not. But to become aware every day that one will soon die is the best aid to life. Almost all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure simply fall away in the face of death. Only what really counts remains. And that is the traces we have left in our environment. May they be good, like those of Johann Sebastian Bach and Mozart, or terrible, like those of Hitler and Stalin or other horrors of history.

Older people should therefore take stock. I always hope that older people have the same luck as the man in one of Bertold Brecht’s stories: he stood in the New York snowdrift in November and asked passers-by for a place to sleep for one of the many homeless people in the streets, and sometimes he was successful. He then concluded that while this did not change the world, some of these homeless people would have a roof over their heads for a night and not get wet. Sometimes streets are named after people, and in fifty years no one knows who gave the name. It seems more sensible to me to provide roofs over the heads of the lost.

Personally, I have gone through the steel bath of the Catholic catechism and after overcoming this purgatory and terror of hell – thou shalt / thou shalt not – I don’t know what will be after my short glow. According to particle physicists, we live in a polyverse consisting of trillions of universes. At least this puts the anthropocentric view of our existence into perspective. After all, we don’t know what billions of people experienced when they set out into the unknown before us. However, I believe I know that some of my patients got better after they had been treated by me.

And so my comfort remains with the verses of the poem “Aus Fernen, aus Reichen”, written by the pastor’s son Gottfried Benn:

“What then after that hour

will be, when this has happened,

no one knows, no news

ever came from there,

from the choked fires,

of the broken light,

it will be rekindled,

I think not.

But I see a sign

across the shadowy land

from far away, from riches

a great, beautiful hand,

that will not touch me,

Space will not permit it:

but I will feel it

and that is you.

And you will glide down

on the beach, on the sea,

from far away, from far away:

“- redeemed he too”;

I knew thy looks

and in the deepest bosom

you gather our fortunes,

the dream, the lot.

A day is ended,

the hoops are taken away,

then two hands play

the song of the night,

from the room where the keys

the dark sound fades away,

you can see the sea and the masts

high to the north.

When the night will give way,

when day has begun,

you bear signs

that no one can interpret,

secret marks

of distant hours ill

and empty the bowl

from which I drank before thee.”

I remember Gottfried Benn sarcastically replying to an objection from an audience member at a lecture: “a higher truth from your mouth, what’s that all about?” How could Benn’s aesthetic conflict be better expressed than in the verse “- eröst auch er”, whose gleam of hope stands in sharp contrast to the finding of nothingness?

Thus the final verses of Benn’s 5th poem of “Epilogue 1949” also take on their meaning:

“The many things that you seal deep

Through your days you carry with you alone,

which you never unlocked in conversation

In no letter or glance you let them in.

The silent, the good and the bad,

the ones you’ve suffered, the ones you’re walking in,

you can only solve them in that sphere..,

in that sphere where thou diest and rises again.”

More than just the afterglow, more than the street name or a grave of “the good and the bad”, which nevertheless all disappear from memory, the unsaid, but also the forgotten, seem, like the unknown poet of the cantata, to want to outlast the times and come again and again.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).