Selig ist der Mann, der die Anfechtung erduldet

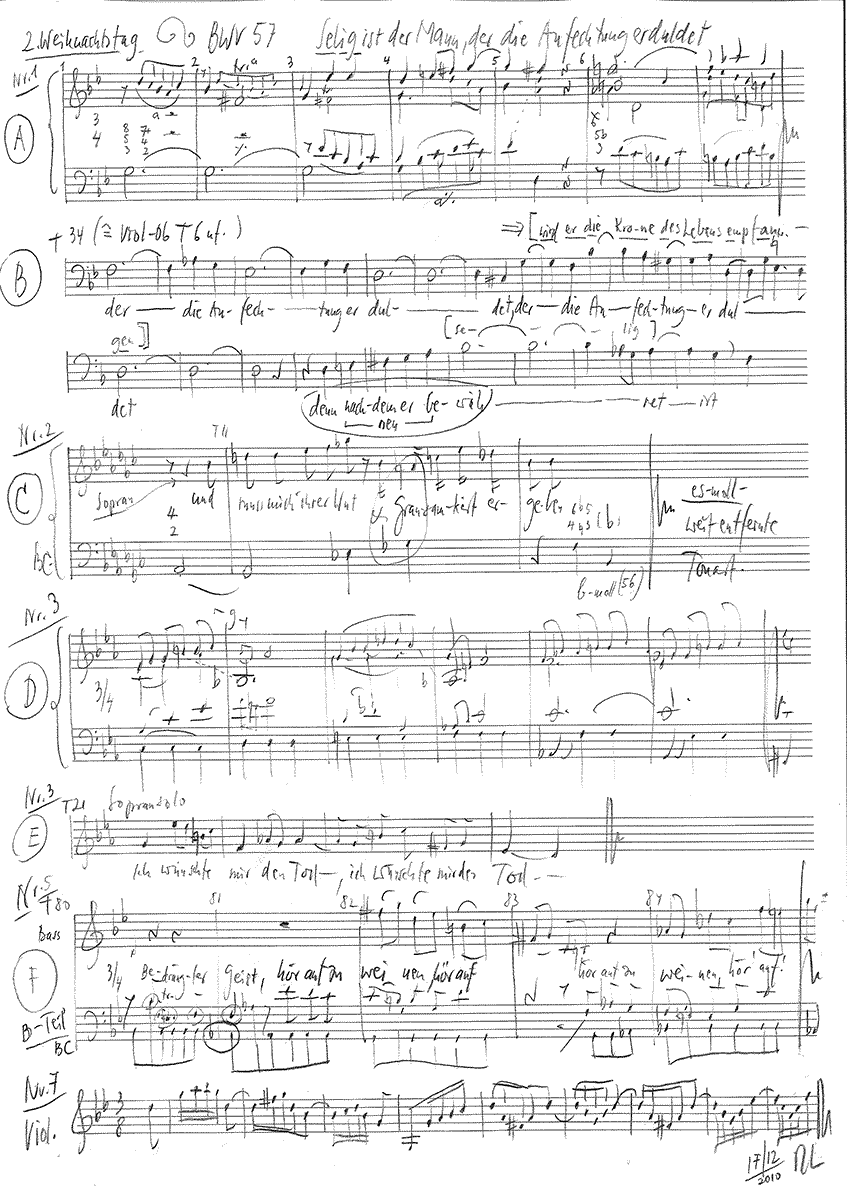

BWV 057 // For the Second Day of Christmas (St Stephen)

(Blessed is the man who bears temptation with patience) for soprano and bass, alto and tenor from the vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, oboe da caccia, strings and continuo

Fittingly annotated by Bach as a “Concerto in Dialogo”, the cantata “Blessed is the man who bears temptation with patience” (BWV 57) again features a dramatic discussion between Jesus and the faithful soul – albeit under very different circumstances than in BWV 140.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Plamena Nikitassova, Monika Baer, Christine Baumann, Sylvia Gmür, Martin Korrodi

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Maike Buhrow, Thomas Meraner

Oboe da caccia

Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Annemarie Pieper

Recording & editing

Recording date

12/17/2010

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Quote from James 1:12

Text No. 2–7

Christian Lehms, 1711

Text No. 8

Ahasverus Fritsch, 1668

First performance

Second Day of Christmas,

26 December 1725

In-depth analysis

The suffering of Saint Stephen, the first of the Christian martyrs, is evoked in the opening aria through doleful melodic sequences, sighing gestures and fraught harmonies, setting the scene for Bach’s contemplation on a godly life and death. While in the previous cantata “Awake, arise” a tender bond of love is sealed between the soprano and bass, the intensely moving aria “I would now yearn for death, if thou, my Jesus, didst not love me” treats the existential affliction of the human heart. Extreme descending intervals, heart-wrenching vocal lines and a brittle timbre invoke an oppressive sense of abandonment; the music depicts a distress so acute it that can only be relieved through the grace of Jesus (recitative “I stretch to thee my hand”).

As in a baroque opera, the work’s emotional metamorphosis comes about suddenly and violently. In the indomitable aria “Yes, yes, I can thy foes destroy now”, Jesus, in a show of might, declares his power to open the heavens and to blow away all “clouds of trouble” – not just for the dying Stephen but also the angst-ridden human soul. With this moment of epiphany, the impasse is broken, and the arising sense of consolation and inner peace is subsequently expressed in an impassioned recitative. Here the soul responds to Jesus’ eternal promise of salvation with alonging for death and the desire to soar aloft to the heavens. The following aria “I’d quit now so quickly mine earthly existence” then unfolds into an exemplary display of baroque denial of the world. Accompanied by a turbulent obbligato violin and a fleeting continuo, the faithful soul becomes increasingly immersed in the wish for death and the renunciation of earthly life (“My Saviour, I’d die now with greatest of joy”) – a distraught emotional state that Bach underscores by ending the aria with a question: “Here hast thou my spirit, what dost thou give me?”

The answer comes once again from Jesus Christ, not in a further solo, but through a chorale. In this closing movement, the text and music of the simple, yet exquisite repeated hymn verse hark back to the church and practice of faith as the scene of the “test” addressed at the beginning of the cantata. It is thus no coincidence that the bass part to the chorale line “out of this thy tortured body” replicates the related passage “for when he hath withstood the test” from bars 48 and 49 of the opening aria. In this cantata, the path to heaven is a tangible journey leading the believer through the suffering on the cross and, repeatedly, through humiliation.

Libretto

Anima (Sopran)

Jesus (Bass)

1. Arie (Bass)

Selig ist der Mann, der die Anfechtung erduldet;

denn nachdem er bewähret ist,

wird er die Krone des Lebens empfahen.

2. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Ach! dieser süsse Trost

erquickt auch mir mein Herz,

das sonst in Ach und Schmerz

sein ewigs Leiden findet,

und sich als wie ein Wurm in seinem Blute windet.

Ich muss als wie ein Schaf

bei tausend rauhen Wölfen leben;

ich bin ein recht verlassnes Lamm,

und muss mich ihrer Wut

und Grausamkeit ergeben.

Was Abeln dort betraf,

erpresset mir auch diese Tränenflut.

Ach! Jesu, wüsst ich hier

nicht Trost von dir,

so müsste Mut und Herze brechen

und voller Trauren sprechen:

3. Arie (Sopran)

Ich wünschte mir den Tod,

wenn du, mein Jesu, mich nicht liebtest.

Ja, wenn du mich annoch betrübtest,

so hätt ich mehr als Höllennot.

4. Rezitativ (Sopran, Bass)

Jesus:

Ich reiche dir die Hand

und auch damit das Herze.

Anima:

Ach! süsses Liebespfand,

du kannst die Feinde stürzen

und ihren Grimm verkürzen.

5. Arie (Bass)

Ja, ja, ich kann die Feinde schlagen,

die dich nur stets bei mir verklagen,

drum fasse dich, bedrängter Geist.

Bedrängter Geist, hör auf zu weinen,

die Sonne wird noch helle scheinen,

die dir itzt Kummerwolken weist.

6. Rezitativ (Sopran, Bass)

Jesus:

In meiner Schoss liegt Ruh und Leben,

dies will ich dir einst ewig geben.

Anima:

Ach! Jesu, wär ich schon bei dir,

ach striche mir der Wind schon über Gruft und Grab,

so könnt ich alle Not besiegen.

Wohl denen, die im Sarge liegen

und auf den Schall der Engel hoffen!

Ach! Jesu, mache mir doch nur,

wie Stephano, den Himmel offen!

Mein Herz ist schon bereit,

zu dir hinaufzusteigen.

Komm, komm, vergnügte Zeit!

du magst mir Gruft und Grab,

und meinen Jesum zeigen.

7. Arie (Sopran)

Ich ende behende mein irdisches Leben,

mit Freuden zu scheiden verlang ich itzt eben.

Mein Heiland, ich sterbe mit höchster Begier,

hier hast du die Seele, was schenkest du mir?

8. Choral

Richte dich, Liebste, nach meinem Gefallen und gläube,

dass ich dein Seelenfreund immer und ewig verbleibe,

der dich ergötzt

und in den Himmel versetzt

aus dem gemarterten Leibe.

Annemarie Pieper

“When soul and body meet at eye level”.

Paradise on earth instead of consolation in unattainable eternal bliss.

I read the text of the cantata “Blessed is the man who endures temptation” as a drama in five acts, which opens with a prologue and closes with an epilogue. The speakers are the soul and Jesus. In the course of the drama, the soul, despairing of the meaning of life, draws increasing consolation from the Christian faith, until in the end it finds its salvation and thus its happiness: in the love of Jesus, who as Saviour becomes the link between man and God.

Let us go through the eight text sections of the cantata in detail. The first section opens the drama with the prologue: “Blessed is the man that endureth temptation; / For after he is tried, / He shall receive the crown of life.” Happiness, the bliss that people long for, is not a result of chance that falls unexpectedly into someone’s lap because the goddess Fortuna has just emptied her cornucopia over them, without merit and regardless of the person. Nor does luck owe itself to an activity, a personal achievement, as signalled by the proverb: Everyone is the architect of his own fortune.

“Blessed is the man who endures adversity.” This happiness comes from a passive attitude, a suffering. And the suffering is related to a contestation. The word “contestation” has disappeared from everyday usage. Instead of “it doesn’t bother me”, today we say “it leaves me cold”, “I don’t care” or “it doesn’t scratch me”. But “challenge” means more than a harmless fencing blow that only leaves a harmless scratch. The challenge referred to in the text means an injury so deep that it calls into question everything one has ever thought to be right and good. It provokes a total loss of meaning. Radical existential doubt devalues life.

The challenge pulls the rug out from under a person’s feet: like Job, from whom everything was taken; like Abraham, who was to sacrifice his son Isaac. How can one prove oneself as one who is so challenged? Not by arming oneself for battle and fighting back, but by patiently bearing the monstrous imposition. God, from whom the challenge emanates, is too powerful an opponent; he cannot be defeated. Proving oneself means: proving oneself to be a reliable, faithful follower of God despite all despair about the fate decreed by God. The firm belief that this God will ultimately not inflict anything unbearable on you makes you patient and confident, so that doubt about meaning is silenced. The allusion to the prophet Stephen (from the Greek “stephanos” = crowned), who was stoned to death for his unshakeable faith, shows that a person can even conquer death if he withstands the challenge. He is awarded the laurel wreath, the crown of eternal life.

The 2nd section leads into the first act of the drama. A man who, like Stephen, believes himself to be in a hopeless situation, lamentingly describes his existential distress. Forced to live like a “sheep” among “wolves”, constantly in fear of having to share Abel’s fate, the I describes his state of mind: he feels lonely and abandoned, defencelessly exposed to the cruelty of his fellow human beings. How painful this life is is signalled by the comparison with a trampled “worm” that “writhes in its blood”. The blood, a symbol of life, no longer pulsates in the body but has flowed out of it. In death convulsions, he rolls in his own blood, kept alive only by the thought of Jesus, who keeps his heart beating. Without Jesus as a model, whose suffering on the cross points the way for overcoming the fear of death, the courage to survive would be lacking. Life would be bleak, filled with excessive grief, which expresses itself in a “flood of tears” in view of the impossibility of opposing the misfortune of earthly existence with one’s own strength.

In the second act of the drama (3rd and 4th section), Jesus, who was only addressed in the first act without having a word to say, gets a voice of his own that promises the suicidal I salvation from his distress. The despondent I pleads for love. Should Jesus turn away from him, the disappointment would be worse than all the torment of hell. For then the I would be lost for good. There would be nothing left to hold on to and lean on. But Jesus assures him that he can count on his love and support. The I understands this to mean that Jesus has the power to keep the enemies of the I at bay and thus protect it from their attacks.

The third act (5th section) brings the turning point, the peripetism of the drama. Jesus confirms to the I that he is able to defeat its slanderous enemies. He then appeals to the I to get a grip and see his desperate situation in a new light: “Afflicted spirit, stop weeping.” The turning point is that the I is urged to reconsider its own abilities and to cooperate in its redemption, instead of expecting that a higher power will, as if by magic, change everything for the better at one stroke. Although the I can trust that Jesus will help him to cope with his difficult situation, he must act himself, overcoming his doubts about the meaning of existence by looking to Jesus as a role model.

In Act IV (section 6), Jesus once again assures the I that in his bosom lie “rest and life”: he is the source of that peace of mind which the Stoic Seneca called “tranquillitas animi”, serenity in the face of the vicissitudes of life. The promise of an eternal life, independent of space-time conditions, prompts the ego to longingly wish for death; now no longer, as in the first act, to put an end to its unbearable existence, but, like Stephen, to reach heaven. Heaven as the opposite place to earth stands for peaceful communion with the angels and God, in which no one is another’s wolf any more, because all are bound together by love. What frightens most people is that the idea of lying dead in a coffin, deprived of all earthly pleasures for ever, gives the ego almost pleasure, because in the anticipation of the happiness of the hereafter it forgets all the torments of earthly existence and ardently desires death, because with it the gate to real life opens.

The fifth act (7th section) contains the finale. The exultant I would like to die on the spot in order to hand over his soul to Jesus, even if he does not know what he can expect in return. What is certain, however, is that it will find its salvation, its bliss, in divine love. In its impatience and impetuous desire to leave life behind as immediately as possible, it misses the fact that Jesus has tried several times to curb its exuberance. As long as it lives, it must prove itself in this world. However, since it feels accepted by Jesus and can build on his promise to be permanently united with him “one day”, it will better endure life here with this comforting prospect – until its end. The drama concludes with an epilogue (8th section) in which the I is once again expressly confirmed that it has a spiritual ally in Jesus, provided it believes in him with unconditional devotion. Faith means: to love Jesus as God who is able to do everything. He will lead the soul liberated from the body to a place where it is blessed, untroubled by physical impairments and psychologically burdensome challenges.

I would like to supplement my attempt to interpret the drama of human existence from a Christian perspective as close to the text as possible with a philosophical reading. The dialogue between the I and Jesus can also be interpreted as a soliloquy of the I, in the course of which the soul triumphs over the body. The body-soul problem has always preoccupied philosophers. The Pythagoreans described the body as the prison of the soul, which it can only leave after death. Plato used the image of the cave to describe the soul’s abode in the dark seclusion of the interior of the body. The “wolves” that attack the soul are the uncontrolled drives and desires whose urge for satisfaction suffocates the soul’s spiritual needs.

Having to live in a body is the greatest misfortune that can befall a living being endowed with spiritual-soul interests. The poet Sophocles had therefore claimed that the best thing is not to be born at all; the second best thing is to die young. Socrates argued that one must practise dying throughout one’s life, that is, begin here to detach oneself from the body by pushing back material desires as far as possible and concentrating fully on the interests of the soul.

The fact that the soul is stuck in a body that ties it to the ground with its earthly heaviness and prevents it from ascending to heaven to find peace on the islands of the blessed was interpreted as the result of a self-failure. By giving in to the insatiable desire for material fulfilment, the soul neglected its spiritual tasks. As punishment, it was banished into a body with the demand to learn to control it. Instead of blaming itself, however, the soul made the body the scapegoat, which it mercilessly makes pay for its predicament. Thus, the roles have been reversed: the soul has become a wolf, venting its rage on the body. But the pain of the body, which has been declared the enemy, also affects the soul, which has to live in and with this body. Philosophically, there are only two ways out of this inner conflict. One is similar to the Christian solution: the soul endures life, hoping that its immortality makes it superior to the perishable body. It consoles itself with the thought that after death it will be free and without guilt if it succeeds in practising asceticism and curtailing sensual desire to a large extent, so that it has enough room for exploring its own spiritual entities and ideal constructs.

The other way out of the dualistic division of the human being provides for a revaluation of the body so that body and soul can meet on an equal footing. Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the philosophers who declared war on the hostility and contempt for the body in Western Christian metaphysics and advocated equal rights for body and soul, body and mind. The soul finds solace not after the death of the body in a distant afterlife, but here and now in a just balancing of bodily and spiritual claims. “You have wild dogs in your cellar”, set them free, Nietzsche advises. Then the soul will also be free; free from its role as prison warden and free to deal with the body based on wise counselling, which, as a partner no longer defamed, finds pleasure in the soul’s sensualised designs for happiness.

In both philosophical controversies about the body-soul drama, it is the voice of reason that takes the Jesus part from the Christian model: On the one hand, pure reason, which makes itself the advocate of the soul and endures the contestation of the body with stoic composure; on the other hand, what Nietzsche calls the great reason of the body, which allows itself to be contested neither mentally nor physically, but ensures that the adversaries, instead of tearing each other apart physically and psychologically, are led to participate in a way appropriate to them in the shaping and realisation of the individual life plan. True art of living consists in coordinating the different interests of head, heart, hand and belly in such a way that they contribute in solidarity, each part in its own way – rationally, emotionally, manually and affectively – to the joy of living of a healthy organism as their common goal.

The I in our cantata experiences the world as a vale of tears from which it wants to disappear as quickly as possible. It seeks its happiness in a paradise, in the community with persons who take to heart the principle of neighbourly love that Jesus embodies. Those who, like Stephen, are immediately confronted with death in an extreme situation may indeed console themselves with the thought that everything will soon be over and that the happiness lacking in this world will be compensated for in the hereafter by an eternal bliss.

However, those who, like most people, have to struggle with everyday worries and hardships cannot simply steal away into a private paradise as it exists in their imagination. Rather, as social beings, we all have the duty to agree on a common ideal and to use our strength to realise this ideal already here and now as best we can under space-time conditions. Why should we not succeed, with united efforts, in transforming the vale of tears into a paradise here on earth on the basis of solidary interpersonal relationships with the help of the Jesus principle, instead of consoling ourselves with the hope of an eternal bliss that is unattainable for living human beings?

Literature

– Søren Kierkegaard, Unscientific Postscript, Part 2, Düsseldorf/Cologne 1958

– Friedrich Nietzsche, Also sprach Zarathustra, KSA, ed. by Giorgio Colli and

Mazzino Montinari, Munich/Berlin 1980

– Plato, Politeia, ed. by Otfried Höffe, 2nd ed., 2005

– Lucius Annaeus Seneca, De tranquillitate animi / On the Equilibrium of the Soul, transl. and ed. by Heinz Gunermann, Stuttgart 2002

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).