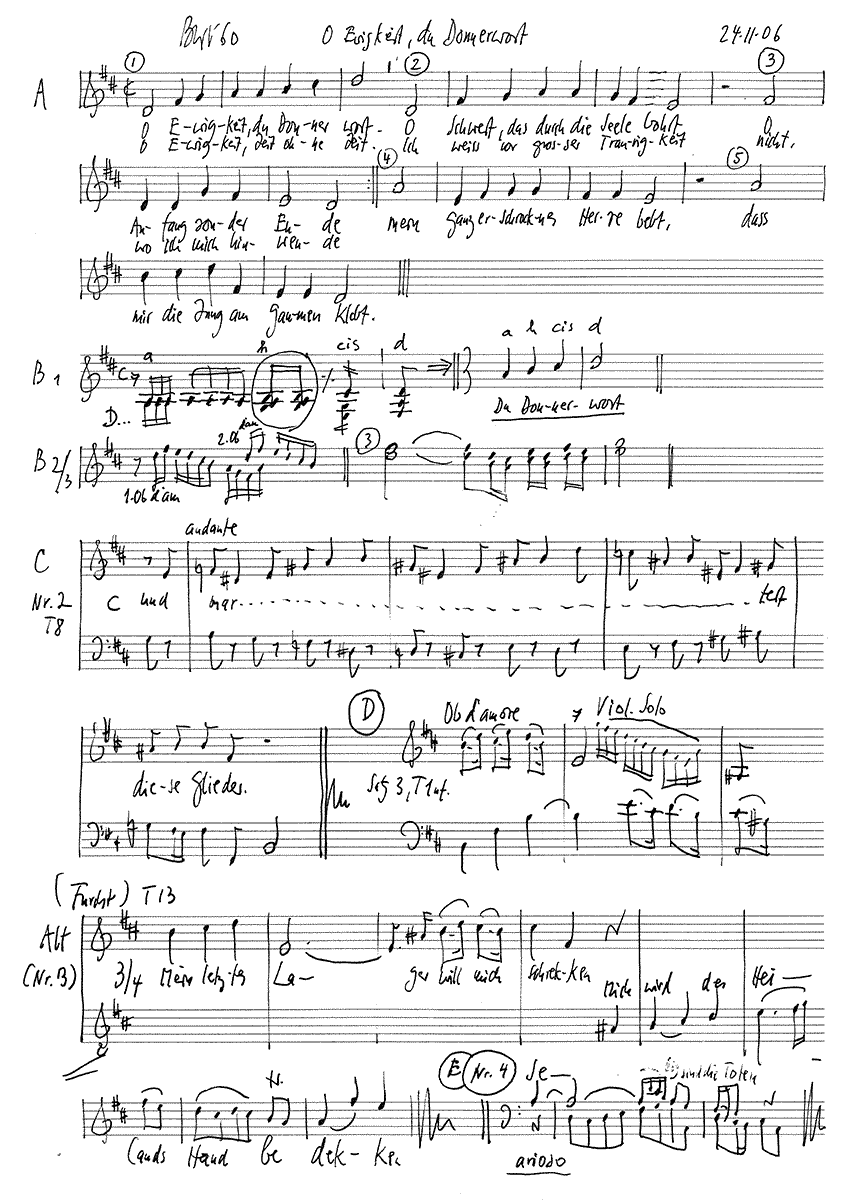

O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort

BWV 060 // For the Twenty-fourth Sunday after Trinity

(Eternity, thou thundrous word) for soprano, alto, tenor, bass, oboe, oboe d‘amore I+II, strings and continuo.

When composing the cantata “O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort” (Eternity, thou thunderous word) BWV 60, Bach was faced with a particularly interesting challenge. In contrast to the chorale cantata BWV 20 which also begins with the same church hymn, this libretto takes the form of an intimate and intense dialogue. It does not, however, portray a dispute be-tween two real persons as is common in baroque operas and oratorios, but instead dram-atises the clash of two conflicting powers of the soul – “Fear” and “Hope” – which mirror man’s inner struggle with the fundamental questions of faith. In fitting allusion to the torn nature of human beings, the libretto does not allow these emotions to speak in an orderly fashion; indeed, the text is strewn with constant interjections and occasionally simultaneous exclamations. As a result, Bach was forced to conceive musical devices that, contrary to the baroque penchant for clear interpretive affect, allow both emotional worlds to serve equally as the foundation for the work.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Soprano

Miriam Feuersinger

Alto

Claude Eichenberger

Tenor

Bernhard Berchtold

Bass

Markus Volpert

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martina Jessel

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Meike Gueldenhaupt, Katharina Andres, Priska Comploi

Organ

Rudolf Lutz

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Peter Gross

Recording & editing

Recording date

11/24/2006

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Johann Rist, 1642 and

1. Gen. 49:18; Psalm 119:166

Text No. 2, 3

Poet unknown

Text No. 4

Revelation 14:13

Text No. 5

Franz Joachim Burmeister, 1662

First performance

7 November 1723, Leipzig

In-depth analysis

The opening aria begins with trembling repeated notes in the strings over a sustained bass note, musically introducing the two opposing aspects of the word “eternity”. By alluding not only to the permanence of eternity but also to the terror of eternal damnation, Bach evokes the multi-faceted nature of fear. Whereas the composition employs a chorale setting until the beginning of the fourth line, the musical character changes swiftly with the entry of the tenor. Two oboes d’amore, whose initial themes had no clear affiliations, now emerge as the partner of Hope, singing defiantly in their upper register against all despair. Aside from their warm, rich timbre, the symbolism of the name “oboe d’amore” also certainly influenced their inclusion in this section. On an intertextual level, Martin Luther’s admonishment that one should not ask for specific alms, but alone for God, is impressively implemented here with the insistent repetition of the phrase “Lord, I wait now for thy help”.

In the first recitative, the reasons why man succumbs to doubt are clearly named: fear of death and the burden of sin. Despite the comforting affirmations of the tenor, Bach’s familiarity with the trials of earthly life becomes evident in his chromatic painting of the word “torture” (sung by Fear) and its inverse musical answer on the word “endure” (sung by Hope). In this passage, the effort involved in enduring life’s burdens is all too keenly felt.

Bach devised the following aria – a feisty minuet – as a double dialogue. Aside from Fear and Hope fiercely trading vocal blows, an oboe d’amore and a solo violin are likewise engaged in a duel. Their starkly contrasting motifs of dotted-rhythmic gestures from the oboe d’amore and racing scales from the violin heighten the impression of an all-encompassing uncertainty. When then the “cruel” sight of the “open grave” is then mentioned, this may well sound disrespectful to today’s listeners. For contemporaries of the baroque period, however, coping with death and dying was a daily issue. Bach himself was orphaned as a child and lost his first wife as well as several of his children to death; accepting irreversible acts of fate was a part of life. Consequently, when Hope declaims the grave as a redemptive “house of peace”, this does not signify an empty gesture of comfort or a mere play on words, but rather a confidence born from the acceptance of human destiny.

Nevertheless, in recitative no. 4, Fear summons his strength for one last attack, to “hurtleth nigh all hope to its destruction”. Hope, in response, takes refuge in a bible passage sung in arioso style which ever so gradually lays bare a secret of deep faith: “Blessed are those, who in the Lord have diéd, from now on”. The phrase “from now on” reveals that salvation shall be given to all believers from this day forward and serves as the works catalyst. For the first time in the entire cantata, Fear is then granted the last word because doubt and terror have lost their power through the promise of the resurrection. The musical tension of the dialogue has been resolved.

The final chorale “It is enough lord, then let me rest in peace”, based on a melody by the Mühlhausen organist Johann Rudolf Ahle, is justifiably one of Bach’s most famous settings. Centuries later, its unusual opening of three ascending whole tones, exquisite harmonisation and modified recapitulation of the first text stollen so fascinated Alban Berg that he thoroughly developed the chorale in his violin concerto of 1935. Inscribed to the “memory of an angel”, it proved to be a swan song not only for Manon Gropius, to whom it was dedicated, but also for Berg himself, who died shortly after its completion.

Libretto

1. Arie (Alt, Tenor)

Furcht:

O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort,

o Schwert, das durch die Seele bohrt,

o Anfang sonder Ende!

O Ewigkeit, Zeit ohne Zeit,

ich weiss vor grosser Traurigkeit

nicht, wo ich mich hinwende;

mein ganz erschrocknes Herze bebt,

dass mir die Zung am Gaumen klebt.

Hoffnung:

Herr ich warte auf dein Heil.

2. Rezitativ (Alt, Tenor)

Furcht:

O schwerer Gang zum letzten Kampf und Streite!

Hoffnung:

Mein Bestand ist schon da,

mein Heiland steht mir ja

mit Trost zur Seite.

Furcht:

Die Todesangst, der letzte Schmerz

ereilt und überfällt mein Herz

und martert diese Glieder.

Hoffnung:

Ich lege diesen Leib vor Gott zum Opfer nieder.

Ist gleich der Trübsal Feuer heiss,

genung, es reinigt mich zu Gottes Preis.

Furcht:

Doch nun wird sich der Sünden grosse Schuld

vor mein Gesichte stellen.

Hoffnung:

Gott wird deswegen doch

kein Todesurteil fällen.

Er gibt ein Ende den Versuchungsplagen,

dass man sie kann ertragen.

3. Arie (Alt, Tenor)

Furcht:

Mein letztes Lager will mich schrecken,

Hoffnung:

mich wird des heilands Hand bedecken,

Furcht:

des Glaubens Schwachheit sinket fast.

Hoffnung:

Mein Jesus trägt mit mir die Last.

Furcht:

Das offne Grab sieht greulich aus.

Hoffnung:

Es wird mir doch ein Friedenshaus.

4. Rezitativ und Arioso (Alt, Bass)

Furcht:

Der Tod bleibt doch der menschlichen Natur verhasst

und reisset fast

die Hoffnung ganz zu Boden!

Bass:

Selig sind die Toten;

Furcht:

Ach, aber ach, wieviel Gefahr

stellt sich der Seele dar,

den Sterbeweg zu gehen.

Vielleicht wird ihr der Höllenrachen

den Tod erschrecklich machen,

wenn er sie zu verschlingen sucht,

vielleicht ist sie bereits verflucht

zum ewigen Verderben.

Bass:

Selig sind die Toten, die in dem Herren sterben.

Furcht:

Wenn ich im Herren sterbe,

ist denn die Seligkeit mein Teil und Erbe?

Der Leib wird ja der Würmer Speise!

Ja, werden meine Glieder

zu Staub und Erde wieder,

da ich ein Kind des Todes heisse,

so schein ich ja im Grabe zu verderben.

Bass:

Selig sind die Toten, die in dem Herren

sterben, von nun an.

Furcht:

Wohlan!

Soll ich von nun an selig sein:

So stelle dich, o Hoffnung, wieder ein!

Mein Leib mag ohne Furcht im Schlafe ruhn,

der Geist kann einen Blick in jene Freude tun.

5. Choral

Es ist genung,

Herr, wenn es dir gefällt,

so spanne mich doch aus!

Mein Jesus kömmt;

nun, gute Nacht, o Welt!

Ich fahr ins Himmelshaus,

ich fahre sicher hin mit Frieden,

mein grosser Jammer bleibt danieden.

Es ist genung.

Peter Gross

“Restless is the heart”

Salvation through progress?

Almost three centuries have passed since Johann Sebastian Bach composed the cantata “O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort” in his first year in Leipzig as Thomaskantor. Bach based it on the song of the same title composed by Johann Rist in 1642 and a text written by an unknown hand. Still delighted by the cantata’s final chorale, the cantata’s text, when detached from its musical container, arouses a peculiar feeling of alienation, even disquiet. Even if the music gives no cause for this and the final chorale with its “tritone”, the “diabolus in musica”, as the three whole tones that follow it were called, need not be perceived as ‘outrageous’ at all by listeners who have been tested with contemporary music, the text nevertheless transports us to a sunken, alien world which, when we try to remember it, slips away like a dream.

The cantata “O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort” (Eternity, Thunder Word) recalls a world that probably shaped and accompanied the childhood of many, from table prayers to the “Rorate Mass” attended daily in Advent, to which we were already taken as kindergarteners early in the morning in the freezing cold, pulled by our mother on the sleigh. Church hymns are also remembered, the sudden sound of which on the radio still evokes the heaviness and sweetness of childhood experiences: “O head full of blood and wounds, full of pain, covered with scorn (…)”. Even if the memory is clouded by the experiences of guilt and shame and by the spiritual exercises of confession and penance, images of a peculiar weightlessness, redemption and happiness have nevertheless remained. Even the martyrs posted on the altar wings, be it the mal- trated Sebastian or the flayed Laurentius, not to mention the crucified Saviour, exuded this peculiar aura of serenity, a metaphysics of suffering whose substantial meaning for the Christian message remained peculiarly alien to the child’s head even then.

Images of death and resurrection

Images of redemption and death, of grief and happiness are taken up by the text of the cantata “O Eternity, Thou Word of Thunder”. It adds the Christian view of death to the Christian world view and raises the most serious questions that man has to face, namely the questions of whether everything comes to an end with death, whether death is justifiable or a scandal, whether it makes our life possible in the first place or impairs it in such a way that man cannot endure his life without the thought of redemption from death. The cantata text ties in with the Gospel (Matthew 9:18, Mark 5:35-53 and Luke 8:49-56), the story of the raising of the daughter of Jaïrus, and presents death to man in such a way that he must think of his own. Fear (alto voice) and hope (tenor) alternate – a dialogue that continues into the instrumentation of the cantata. In the fourth movement, the recitative and arioso, the bass then resounds with the vox Christi, the voice of the Redeemer, which calls out in three verses, repeating and varying and increasing at the same time: “Blessed are the dead / (…) Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord / (…) Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.”

Musically, the second verse repeats “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord.” in the tonal gesture of dramatising and deepening (and therefore transposed up a tone) repeats the first (“Blessed are the dead”), while the third (“Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.”) is the essentially extended variation of the preceding one. The conclusion of the recitative sounds a hopeful, well-tempered fear, describing her conviction, indeed her conversion, through the vox Christi thus: “Well then! / Shall I be blessed from henceforth: so set thou, O hope, again! / My body may rest without fear in sleep, / The spirit may do a glimpse of that joy.” But: do we share this hope? Can we now and today sing the “Wohlan!” and “Es ist genung” in a calm and joyful manner? Does the cantata live from this motif? How would we hear the cantata if it did not have the Christian message of salvation? Would it then lose its depth? Would it move us less? Does the text even allow for other than Christian readings? My hypothesis is: the text as such does not. But the music is certainly capable of evoking a new, no longer only Christian reading.

God as judge and reaper

First of all, to the extent that the aforementioned Christian world and death view structures this text in terms of perspective, it also offers the corresponding vocabulary: Heart, pain, body, soul, eternity, temporality, hell and heaven. Sin and hope. And finally death, finitude and eternity. The substance of Christian messages implied in this vocabulary, condensed in the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed, and proceduralised in worship, liturgy and Eucharist, can be summarised in three points: First, the world “is” two worlds. Or: The world is not enough. A world on this side is encompassed, underpinned by a world on the other side. Secondly, the world on this side is a fallen world. Man sinned before time immemorial, and this sin has been propagated from generation to generation with procreation ever since. The punishment for sinfulness is expulsion from the blissful eternity of paradise and finitude. Death is ultimately “the wages of sin” (Romans 6:23). And thirdly: we are redeemed into an otherworldly, different, transcendent, an eternal world. And that is through a Redeemer who came because man cannot redeem himself and will come once more to judge us on the last day. And who wipes away all tears from some and casts others into eternal doom.

The belief in sin and redemption, in rebirth and eternal blessed life is, as in the other religions of salvation, especially in Judaism, strictly permeated by the view that history has a beginning and an end and that the definitive end of history is preceded by the apocalyptic time of messianic travail. This view of the world and death, and especially the idea of the end of the world, of a finale, of a final end, when God comes to us as a reaper and judge and separates the good from the bad, taking some with him to the kingdom of heaven and condemning others to hell and eternal suffering – this end is by no means a comforting message, but rather arouses the deep disquiet that was mentioned at the beginning. Why is this so?

First of all, this, our dear God, also bears the cruel features of a God who does not forget and punishes man for something for which he himself cannot be responsible. God’s civilisation is indeed underway (a blasphemous thought when one thinks of his perfection), on the one hand by concealing his barbaric features and the horrible hell in the hereafter, and on the other hand by speaking only of salvation and no longer of disaster, only of heaven and no longer of hell. Indeed, in the Christian Church there is a kind of agreement of silence about the last things. This corresponds to the nature of our thoroughly secularised society.

But has not the Christian idea of the end times been forced down to earth here, into our everyday life practice, and has the calling from God been secularised into an everyman’s calling? Is our modern faith in progress not a slave to the Christian story of salvation? Are we not ultimately driven by the idea of wanting to go to heaven alive? The disquiet intensifies when we include other worldly spheres. If the world and death views of the religions of redemption, together with their temporal relationship structures, are thought to belong to the earth, worldly redeemers take the place of the divine ones. They then raise their voices and set goals, ways and solutions, which often enough have the character of final solutions. It is by no means the case that only the national socialist, fascist and communist promises of finality worked with the arsenal of Christian messianism: with finales, messianic travails, apocalyptic horsemen and the end of time. The semantics of redemption was and is a consistent feature of any idea of progress that takes hold of a society, in the past as well as today.

Moreover, there are obvious signs of fatigue that have their origin not in the deteriorating data on the state of the world, but in the failure of individual self-redemption projects, be they mystical, toxic, sexual or measurable in decibels. Paradises, as they were still painted in the utopias and futuristic scenarios of the 18th and 19th centuries, are diminishing in luminosity. No light at the end of the tunnel. The fateful missions with their doctrines of salvation and marching orders have triggered historical and human catastrophes on an unparalleled scale. But also the inner-worldly and gnostic ideas of self-redemption have given way to weariness. Not to mention the migration of ideas of salvation into interpersonal constellations.

Renaissance of religion – what religion?

In this sense, today, at least in the discussion about the meaning and goal of history, there is a noticeable abandonment of the idea of final solutions and an associated end of history. The teleological idea derived from the Christian calendar, according to which world history is heading for a finale and will give birth to a kind of inner-worldly ecclesia, a world community, is also called into question due to the increasingly noticeable marginalisation of the Western cultural sphere and the unforeseeability of future developments. The bright future that has so far cast its shadow on the present has itself faded: “no more crazy, glorious faith, no more open horizons, no more mirages, no more breath-curbing utopias, but the winding up, the stint”, as Arnold Gehlen put it.

However, when the improvement of the stay in this world makes no noticeable progress, when nutrition, health, housing and long life of growing masses of people become the general topic and the inner-worldly, the meaningful redemption does not seem to get off the ground, the widespread opinion is that the need for outer-worldly redemption is awakened again. The still, crystallised society then awakens the desire for playgrounds of a higher kind. The widely shared opinion, however, that modernity is on the verge of a return of religion and that religion is moving with force into the vacuum created by the cooling of faith in progress, must of course be questioned as to what is returning under the mysterious word “religion”!

Since the assumption can be made that man – because he is a self-transcending being – is always religious, the unspecific question of a return of religion makes just as little sense as the question of a return of culture. For just as a society without culture is unthinkable, those who pretend to believe in nothing also believe in something. The question is therefore not whether religion will return, but which religion. And the question is not whether there is a God, but whether the Christian God and his Messianic Son are still present in people’s hearts. If the question of the return is already being asked, then as a Christian one must ask whether it is Christianity that is returning. Will the Christian message of salvation and the views of life and death associated with it find their way into people’s hearts? Will the semantics of the end times and of the end of life once again determine life and thus the idea that death is killed and overcome in death – mors mortis – once again be believed as a matter of course? Is the text of the cantata “O Eternity, Thou Word of Thunder” not only “understood”, but does it touch people’s hearts, move them and penetrate them? Or would the message of the cantata’s content not prove to be secondary, even disturbing, if it were “understood”?

Whether with a heavy or light heart, one must admit that the cantata suffers as little if one does not “understand” the song as Verdi or Wagner operas do without understanding their often nevertheless untimely and curious text. The superb setting of the material can be enjoyed without the listener being able to understand the content of the text. It should not be forgotten that Luther’s theology was based on the conviction that the Word of God recorded in the Bible was dead and ineffective unless it was proclaimed, so that the text was of essential importance in the cantata. Accordingly, church music was virtually loaded with text, not the other way around, and, moreover, often sung in German rather than Latin. In Bach’s time, the cantata was a declamation of the sung word, vocal preaching and not simply singing. Today it seems to have been reversed: The text becomes meaningless material while the music rejoices.

Becoming one with imperfection

It is therefore hardly wrong to assume that for today’s audiences, text and word no longer take precedence over melody in any way. Text and words seem to be absorbed into the melody, even to disappear into it, and the declamation of the text at best awakens thoughts of something irretrievably lost. Today, a cantata with a completely incomprehensible text can be performed just as easily as the liturgical chants of Jewish cantors, the litanies of Greek monks or the Orthodox chants of Bulgarian magical voices. One might conclude from this that the Christian message of salvation has lost its power, lost its basis of life in people’s hearts, and that the return of Christ is no longer even remembered when we sing about it in the Christmas carol “Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her”.

In view of the incessant but unsuccessful efforts to move the world forward and prevent disaster, in view of an obvious fatigue with redemption and reform, perhaps it is time to ally ourselves with the unfinished, the provisional, the imperfect. Not only to ally, but to draw strength from imperfection, not to see it as a punishment from God, but as a gift to be guarded and not to be denied or even to be gotten rid of. It may sound paradoxical: In a redeemed world, there would be no cantata and no reflection on it. Cantatas, like music, art and literature, are the peaceful witnesses of an unfinished world that would not exist in a completed one. Something would be missing if one could not hear music. And even more so, as Robert Walser once put it, something is missing when you listen to music. For music makes us sensitive to the lack in which and from which man lives in principle. All true music springs from weeping, according to Emile Cioran. “O eternity, thou word of thunder” – this text, which has become strangely alien, is witness to a time in which this cantata meant a rest on the way to God, a testimony, therefore, that became superfluous when the pilgrims reached the goal of salvation and with their redemption itself. If what should have happened according to the Christian message of salvation had come true, we would be poorer for the experience of a concert evening. It is not only the laments of this cantata that spring from human imperfection and weakness. The heart is restless, Augustine complained, and that is how it should remain.

Literature

– Emile Michel Cioran, Von Tränen und von Heiligen, Frankfurt a. M. 1988.

– Alfred Dürr, Johann Sebastian Bach. Die Kantaten, Kassel, Basel, London, New York, Prague 1999 (8th ed.).

– Arnold Gehlen, Anthropological Research. Zur Selbstbegegnung und Selbstentdeckung der Menschen, Reinbek 1961.

– Peter Gross, Die Multioptionsgesellschaft, Frankfurt a. M. 1994.

– Peter Gross, Ich-Jagd. Im Unabhängigkeitsjahrhundert, Frankfurt a. M. 1999.

– Peter Gross, Beyond Redemption. The Return of Religion and the Future of Christianity, Bielefeld 2007.

– Karl Löwith, Weltgeschichte und Heils- geschehen, Stuttgart, Berlin, Köln, Mainz 1953.

– Johanna Prader, Der Gnostische Wahn, Vienna 2006.

– Jacob Taubes, Occidental Eschatology, Munich 1991.

– Eric Voegelin, Die politischen Religionen, Munich 1993.

– Robert Walser, Fritz Kocher’s Essays, Frankfurt a. M. 1998.

– Max Weber, Zwischenbetrachtung: Theorie der Stufen und Richtungen religiöser Weltablehnung. In: Ders: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Religionssoziologie, Vol. I, Tübingen 1920, pp. 536 – 573.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).