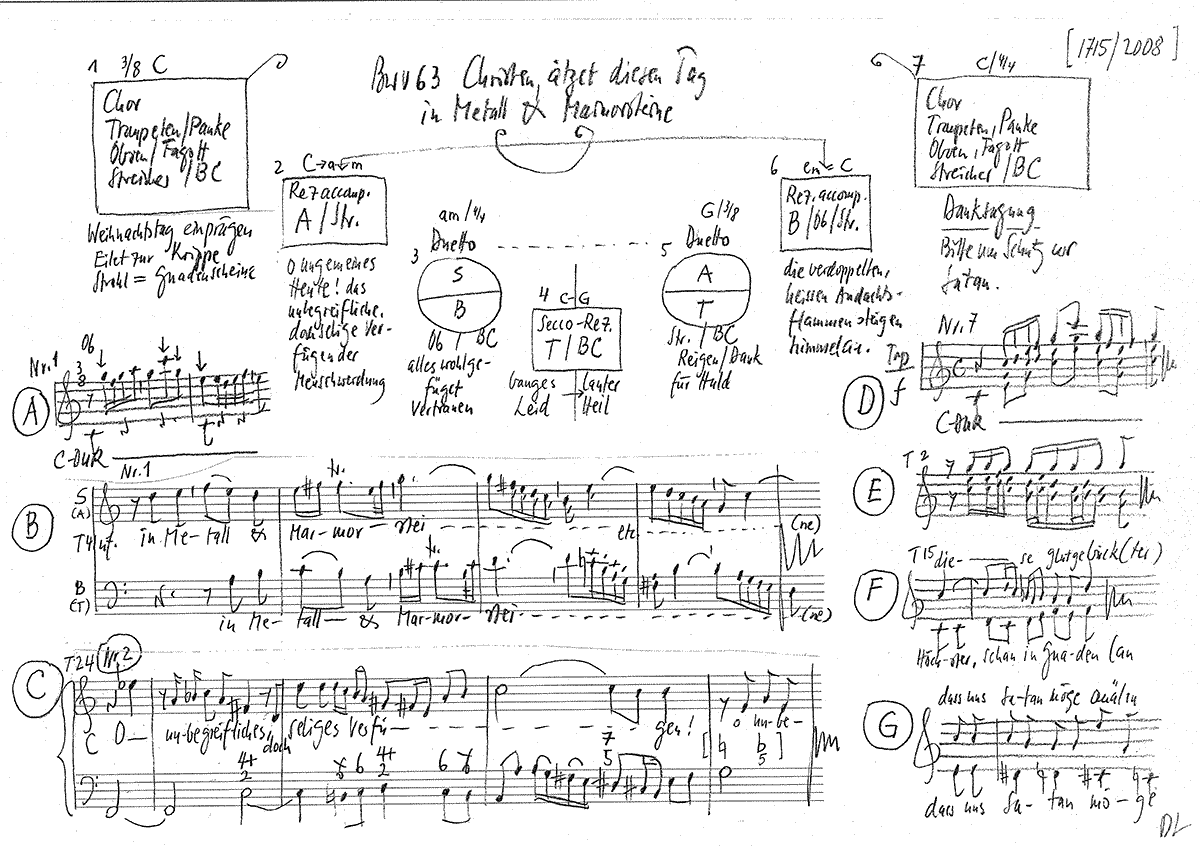

Christen, ätzet diesen Tag

BWV 063 // For Christmas Day

(Christians, etch ye now this day) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpets I-IV, timpani, oboe I-III, bassoon, strings and continuo.

In 1957, Bach specialist Alfred Dürr wrote that BWV 63, more than any other of Bach’s cantatas, strives to unify the highest intensity of magnificence with the maximum level of economy. Indeed, three of its four large-scale movements – the two choruses and the aria – follow a strict da capo form. While it is known that the work was re-performed in Leipzig for Christmas in 1793 and probably also in 1729, the exact origin of the cantata has yet to be determined. The surviving original parts would suggest Bach’s Weimar years of 1713/14; nonetheless, the performance of a cantata with a practically identical libretto by Gottfried Kirchhoff, music director of Halle, for the bicentennial celebration of the Reformation in 1717 indicates that Bach may have written “Christen, ätzet diesen Tag” (Christians etch ye now this day) in 1713 as part of his application for the position of organist at the Marktkirche in Halle.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Mami Irisawa, Jennifer Rudin, Noëmi Tran Rediger

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Walter Siegel, Marcel Fässler

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, Oliver Rudin

Orchestra

Conductor & harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi, Anais Chen, Sylvia Gmür, Christoph Rudolf, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Luise Baumgartl, Esther Fluor, Hanna Geisel

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Klaus Pfeiffer, Michael Bühler

Timpani

Martin Homann

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Iso Camartin

Recording & editing

Recording date

12/19/2008

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Poet unknown

Text No. 1, 3, 5, 7

Based on a text by Johann Michael Heineccius

(1674–1722)

First performance

25 December 1723, Leipzig

In-depth analysis

The introductory chorus opens with an orchestral prelude whose full wind section and powerful tutti rhythms joyfully announce that the dark, musical dearth of Advent is over; Christmas morning is here! The opulent scor-ing for four trumpets, timpani, three oboes and strings is featured only one other time in Bach’s cantata oeuvre, namely in the ceremonial music for the Leipzig council elections “Preise, Jerusalem, den Herren” (Praise, O Jerusalem, the Lord) BWV 119. But Bach is not content to allow the music to simply revel in Christmas joy; rather, he assigns the vocalists a dense movement of coloraturas that focuses more on textual meaning than on rejoicing of the day. Here, the melismas seem to literally “etch” the news of the birth of Jesus Christ into the eternal memory of Christians. At the same time, it may be that Bach, who was raised in a city of craftsmen, wanted to pay homage to the stone masons and engravers who worked so laboriously for the courts and churches of the times. In the middle section of the chorus, the “light” of God’s mercy then breaks forth and emerges as the work’s inspiration.

The inner movements that follow were conceived with particular care. The shimmer-ing string timbre of the recitative “O blessed day! O day exceeding rare” reveals the transcendent spirit of the day, while the repetition of the libretto in the vocal parts and orchestral postlude powerfully evoke the unfathomable act of Christ’s sacrifice. The tenor recitative no. 4 eschews the usual strings and employs instead a virtuosic continuo line to convey the stout courage of the libretto. In the richly orchestrated bass recitative, it seems that Bach, by scoring the accompaniment with both strings and oboes, wanted to interpret the text of “Redouble then your strength, ye ardent flames of worship” literally in the music.

As a rare example, both arias are composed as duets. In the first, a tender adagio, the soprano and bass express their grateful wonderment at God’s love and sacrifice, accompanied by an elegiac oboe cantilena that soars over the saraband-like foundation. In contrast, the alto and tenor duet is accompanied by a full string section that, in a swing-ing 3⁄8 time, calls God’s faithful believers to join together in thanksgiving.

The work concludes with a closing chorus “Highest, look with mercy now” – an unconventional combination of polychoral orchestral concertante passages, catchy choruses and a fugue-like motet. However, the middle section makes all too clear that the idyll of the Nativity and human happiness remain constantly threatened by the malevolence of Satan: Christmas rejoicing and its decorations are but thin veneers masking the temptation, death and (spiritual) privation that pervaded everyday life in the early modern era.

Libretto

1. Chor

Christen, ätzet diesen Tag

in Metall und Marmorsteine!

Kommt und eilt mit mir zur Krippen

und erweist mit frohen Lippen

euren Dank und eure Pflicht;

denn der Strahl, so da einbricht,

zeigt sich euch zum Gnadenscheine.

2. Rezitativ (Alt)

O selger Tag! O ungemeines Heute,

an dem das Heil der Welt,

der Schilo, den Gott schon im paradies

dem menschlichen Geschlecht verhiess,

nunmehro sich vollkommen dargestellt,

und suchet Israel von der Gefangenschaft

und Sklavenketten des Satans zu erretten.

Du liebster Gott, was sind wir arme doch?

Ein abgefallnes Volk, so dich verlassen;

und dennoch willst du uns nicht hassen;

denn eh wir sollen noch nach dem Verdienst zu Boden liegen,

eh muss die Gottheit sich bequemen,

die menschliche Natur an sich zu nehmen

und auf der Erden

im Hirtenstall zu einem Kinde werden.

O unbegreifliches, doch seliges Verfügen!

3. Arie (Sopran, Bass)

Gott, du hast es wohl gefüget,

was uns itzo widerfährt.

Drum lasst uns auf ihn stets trauen

und auf seine Gnade bauen,

denn er hat uns dies beschert,

was uns ewig nun vergnüget.

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

So kehret sich nun heut das bange Leid,

mit welchem Israel geängstet und beladen,

in lauter Heil und Gnaden.

Der Löw aus Davids Stamme ist erschienen,

sein Bogen ist gespannt, das Schwert ist schon gewetzt,

womit er uns in vor’ge Freiheit setzt.

5. Arie (Alt, Tenor)

Ruft und fleht den Himmel an,

kommt, ihr Christen, kommt zum Reihen!

Ihr sollt euch ob dem erfreuen,

was Gott hat anheut getan!

Da uns seine Huld verpfleget

und mit so viel Heil beleget,

dass man nicht g’nug danken kann.

6. Rezitativ (Bass)

Verdoppelt euch demnach,

ihr heissen Andachtsflammen,

und schlagt in Demut brünstiglich zusammen!

Steigt fröhlich himmelan

und danket Gott vor dies, was er getan!

7. Chor

Höchster, schau in Gnaden an

diese Glut gebückter Seelen!

Lass den Dank, den wir dir bringen,

angenehme vor dir klingen,

lass uns stets in Segen gehn,

aber niemals nicht geschehn,

dass uns Satan möge quälen.

Iso Camartin

“The Immense Today or

Christian etchings for the Christmas season”

Of all the things we hold dear, we have not only memories and wishful thinking in our minds, but often sharply drawn images. They are deeply imprinted in us and sit seemingly unchangeable in our brain. We can recall them as long as our memory functions are not impaired by illness or age. Most of the time, these images bring us joy, sometimes sadness, when we bring them back to our consciousness. We are reminded that something that once seemed unlosably close has receded into the distance. The images have remained with us, even though reality has become uncatchable.

In the Christian West, the Christmas season is a time particularly blessed with memories. It brings even hardened and hard-boiled adults back to their own childhood. Waiting for miracles, for surprises, feeling the approach of what we have longed for for a long time, perceiving Christmas lights, songs and scents in the surroundings of the events, combined with the suspicion that it could be even more beautiful and enjoyable than we can imagine: all this is part of our Christmas memory treasure. Or the children’s question: How many more times to sleep? The early darkness of the short days heightened expectations back then. Something unnameably special seemed to be preparing itself. Quietly the snow trickles. “In the hearts it is warm, / quietly silent sorrow and harm.”

Christmas is the time when our susceptibility to belief in miracles and sentimentality has free rein. Like the poor boy in the Grimm fairy tale who found the golden key and the iron box, we wait to learn what miraculous things lie in the magic box. We want to warm ourselves like “The little girl with the matches” in the other story by Hans Christian Andersen, who wants to hold on to the warm stove, the roast goose, the Christmas tree and her grandmother for all the world. We wrap ourselves in manger idylls and shepherd sounds, see the stars shining new and different and hear angelic choirs singing “Peace, peace! on earth!”. And who could blame us for this? Don’t we urgently need a short time once a year in which, at least in our imagination, things are tender, generous and peace-loving?

For bourgeois society, Christmas is a festival of feelings, of family intimacy, of shining children’s eyes. Of course, it’s also a time of strain on the wallet, because for those who know how to do business with our feelings, this is also a time of splendour in gold and silver according to the notes. And we, in a Christmassy mood, are happy for the clever traders and participate generously in the buying frenzy. In sharp contrast to this, however, Christmas stands for Christian thinking, but probably also for philosophical reflection on the sense and nonsense of these recurring winter activities. From a Christian point of view, Christmas is nothing less than the incursion of the divine into the human dimension, the repairing point of a history of salvation that was on the wrong track, the moment of revelation and the beginning of a divine intervention that is supposed to correct man’s constructional error and give his life trajectory direction and purpose again. At Christmas, something radically new dawns, unpredictable, unexpected, undeserved, leaving our imagination far behind and far beyond our grasp. In Bach’s time, people in Christian lands still knew something about this, and that is why his first Christmas cantata does not begin with shepherd’s music and lullabies, but with a drumbeat and the blaring of trumpets, as if the onset of the divine had to be smashed full force into the ears of a sleeping crowd of Christians.

What are the first words of the cantata? “Christians, etch this day / in metal and marble stones!” Is there even a more un-Saintly word than “etch”? It’s about burning in, eating into, hydrochloric and acetic acid attacking and changing surfaces. Until the 16th century, the word was mainly used in the sense of “to be eaten away and grazed by cattle” – hence the expression “the etching”. But by the Baroque period, the word was already being used – now with the a sharpened to ä – as a chemical change reaction that remains visible on the surface. Etching meant: to treat with a sharp liquid and thus to change recognisably. The word “etch” is to the word “eat” as biting is to pickling. Here it is not just a matter of chewing and digesting, here it is a matter of burning, of treating with acid, of getting to grips with what is resistant. Etching reveals the structure of the material, the consistency of metals and alloys. With targeted etching, layers and deep structures become visible anew. Etched figures allow conclusions to be drawn about the crystalline nature of the material from which a thing is made. We now not only see surfaces, but gain insight into deeper inner layers. In the same way that the glowing iron is used to burn an identifying mark into the skin of animals, the Christmas event is to be etched into the soul of Christians. Just as acids and corrosive poisons attack metals and the pores of marble, so the message of Christmas should attack the surfaces of our smooth and dull Christian souls. Whoever has absorbed this message is afterwards a different one, a Christian etched and burned, to whom one must look at the changes. This Christian etching is anything but spiritual medicine. The last lines of the opening chorus emphasise it once more: “For the ray, so da einbricht, / zeigt sich euch zum Gnaden- scheine.” In the breaking in of the insight into what really happened at Christmas, something is supposed to break, even if it is our need for rest and sparing. A ray of light should pass through our cluelessness and shine through it so that a “shine of grace” emerges from it. This can only mean: We are to gain new clarity about who we are and what is incumbent upon us as Christians. Christmas is not the soothing, warm breathing of donkey and ox in the rhythm of “Süsser die Glocken nie klingen” and “Ihr Kinderlein kommet”. For the adult, reflective Christian, Christmas is a beacon for conversion, departure and a new beginning. That is probably why the first chorus of this cantata is such a radiantly undaunted wake-up call. Out of sleep, you Christians! Understand at last: a completely new time is dawning!

Much about this astonishing Bach Christmas cantata lies in the dark and will probably always remain so. We know neither the librettist nor the occasion of the premiere with certainty. The work has a number of oddities that leave even the experts at a loss to explain it. No chorale, no solo arias, three recitatives with hauntingly beautiful arioso parts, opening and closing choruses and two duets, all in da capo form. All this is quite unusual, even for connoisseurs of the wealth of forms in Bach’s cantata works. It need not trouble us. Even the uncertainty about the text poet is not a problem for us. His, and even more so Bach’s, way of thinking about the deeper meaning of the Christmas events is clear enough.

Whether the Halle theologian Johann Michael heineccius was the text provider – as most connoisseurs assume – or whether another divine scholar of the time wrote the text for Bach: the central motif of the message is clear and unmistakable. It is placed in the exact centre of the cantata and reads: “So now today / the anxious sorrow, / with which Israel was frightened and burdened, / turns into pure salvation and grace. Conversion, then. Gone are the fears and burdens, the anguish and bondage, the chains of slavery and the torment of the soul. The tide has turned. Fear is to be turned into courage and confidence, despondency into joy, captivity into freedom. Because – the solution sounds so simple: God became man. In this and in this lies everything. That is what we have to think about. That is the incomprehensible, the beatific, the thing that goes beyond all expectations and ideas: although we would have deserved to lie on the ground, the Godhead “takes human nature upon itself, / and on earth / becomes a child in a shepherd’s stable.” Man, wake up! A “blessed day” has dawned. Understanding this, we suddenly live in a “tremendous today”.

But what is a “common today”? Let us first ask: What would be a common today? A day like any other. An interchangeable day, like many of us experience. Just everyday life. A day, perhaps, on which nothing corrodes us. Where life moves on with us and against us as imperceptibly as it does unmolested. Normality, then. We need normality. We cannot be confronted every day with things that interrupt us, stop us or even throw us off course. Isn’t life often pleasant precisely because nothing gets in our way, because we don’t get out of step, because nothing unforeseeable hinders and worries us? It would be unbearable without utterly mean days when habit, familiarity, uneventfulness and calm prevail. But suddenly the new strikes, like a bolt from the blue. In one fell swoop, everything is different. Where there used to be a path, an abyss opens up. There is no way forward. A turnaround is called for. A change of direction and a change of mind.

This breaking in point of the different is what we call revelation. Nothing is as it was before. Man, finally understand! Only in this way can the common today become the uncommon today. The writer of this cantata text wants the events around Christmas to be understood in this radical way. The breaking off of normality through an experience of salvation that burns itself into the soul. Now is the moment! Only now do you understand how you have been on the way so far, laboriously, crawling on the ground, burdened with fear and guilt. In the light of this experience, the scales finally fall from your eyes. You knew only mean days. Now heaven has given you a tremendous today! The author of the cantata text calls the intervention of the divine in human life an “incomprehensible decree! “God, you have done well, / what happens to us now” sings the soprano and bass voices, wonderfully accompanied by a solo oboe, as if the Holy Spirit himself would like to add his blessing to the singer’s insights through the supple sound of the oboe.

But before that, the old conditions must be considered. In the history of salvation, pretty much everything has gone wrong for man. Through insatiable curiosity and desire for the forbidden, he fell into captivity and into Satan’s chains of slavery. As a rule, we hear little of the devil and his followers around Christmas time. As if hell were on holiday at this time. Not so in our cantata. Satan is very present and at work. He harasses us, he even torments us, as we read. But now it is to become difficult for him. For despite apostasy and betrayal, God does not want to let his creatures perish completely and hand them over to Satan. So he promises to send someone right after the Fall to make up for the guilt and wrongdoing. Here this promised someone is called “the Shiloh”. A strange word that Luther translated simply and clearly as “the hero”, while the Greek and Latin Bibles interpret the Hebrew word as “one who stands ready”, “one who is to be sent”, “one to whom the ruling staff belongs” and who is to restore divine order. The Kabbalists have discovered that the word “Shiloh” has the same numerical value as the word Messiah, so that it may rightly be interpreted as the messenger or prophet of God. Our librettist explains this promised deliverer with another image: “the lion of David’s tribe” comes to us. Of course, this is a very special lion, one who can draw a bow and sharpen a sword, and therefore Luther’s “hero” is probably an extremely apt description. But the real Christmas message and imposition on the mind is that this mighty messenger, who is able to wipe out and make up for the guilt of the weak people of that time, is supposed to be a child in a manger. This is the tremendous thing that the librettist calls the “incomprehensibly blessed disposition” – which Bach makes audible in an emotionally ravishing alto recitative. In the shifting and gentle gliding from one key to another, something of this “incomprehensible disposition” becomes audible to us here. It is so wonderfully successful that one believes that this gifted musician must have learned the musical disposition from the inventor of this salvation story himself.

Of course, the poet also adds a little pietistic-pastoral encouragement. Nor can he suppress his baroque love of the contrary and the paradoxical. How else could he make hot devotional flames beat together ardently in humility? Is it possible to be humble and driven by fervent ardour at the same time? How can this be done? How can such different feelings be combined? Doesn’t the water of humility necessarily extinguish the fire of love? But let us consider: Perhaps, for this poet, the expression “in humility ardent” is nothing other than a wonderful word formula for what he considers to be a specific characteristic of the Christmas miracle. Thus, not only God and the great composer Bach would have achieved an “incomprehensible disposition” on this day, but even our modest anonymous poet. Perhaps one would even have to say that Christmas itself cannot be described more accurately from the perspective of a theologian than with the expression “the incomprehensible disposition”. Here, something was so newly and differently arranged and decreed that in the stream of salvation history, in the midst of everyday life, the “tremendous today” suddenly had to appear.

What happened at Christmas had never happened before. It is so unique and unexpected that every Christian must etch it into his memory so that it will never again disappear from his eyes and his consciousness. Gone are the anxious sorrows, mourning, fear and oppression. The flames of devotion are to flare up, the person can now rush to heaven joyfully and gratefully, even jubilantly. The “stooped soul” will at last be free, it will blossom in love and enthusiasm, and Satan, who often tormented it so badly and deceitfully, shall never again have the opportunity to do so.

How Bach transformed this joy about this “immense today” into music borders on a miracle. When we listen to this cantata, exactly what the text wants to fix in our minds happens to our feelings. In triple eighth time, after the first choral movement, one would like to dance through the world and grab everything by the arm and dance and cheer along. It is music that doubles our enthusiasm when we listen to it, that lets our happiness begin again and again da capo, as it were, without suppressing the incomprehensible in the frenzy of enthusiasm. For this shines forth again and again, in the recitatives, in the interplay of the voices. This music virtually etches in us an insatiable longing for light and joy, for fulfilment and happiness. When the frenzied string figures of the final chorus enter and flit through our ears, we suddenly know: this is what Christmas must be like. A divine whirlwind that grips us, ruffles us, dishevels us, sweeps us along and lifts us out of the common and the foreseeable, out of the ridiculous gloom and the disgusting pettiness of our everyday lives. Here we experience by listening that the “immense today” is there, tangibly close, around us, within us, in the indescribable glow and warmth of this Bach music. “Give thanks to God”, the bass voice admonishes us in the last recitative, “for what he has done”. I would like to add: and let us thank Bach that we can understand the Christmas miracle to some extent thanks to his music.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).