Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt

BWV 068 // For the Second Day of Pentecost

(In truth hath God the world so loved) for soprano and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, oboe da caccia, violoncello piccolo, strings and basso continuo

Information on reflective lecture: For reasons of copyright, the video of the reflective lecture by Hans Magnus Enzensberger is not available online.

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Linda Loosli, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Simone Schwark, Julia Schiwowa, Anna Walker

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Liliana Lafranchi, Alexandra Rawohl, Damaris Rickhaus

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Tobias Mäthger, Christian Rathgeber, Sören Richter

Bass

Grégoire May, Fabrice Hayoz, Daniel Pérez, Retus Pfister, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Martina Bischof, Peter Barczi, Sarah Krone

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violoncello piccolo

Daniel Rosin

Violone

Guisella Massa

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Ann Cathrin Collin

Oboe da caccia

Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Dana Karmon

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Jörg-Andreas Bötticher

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz and Eva Borhi

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Hans Magnus Enzensberger

Recording & editing

Recording date

05/25/2018

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler, Nikolaus Matthes

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Christiane Mariana von Ziegler (1695–1760),

including a verse by Samuel Liscow (1675; movement 1)

and John 3:18 (movement 5)

First performance

21 May 1725

In-depth analysis

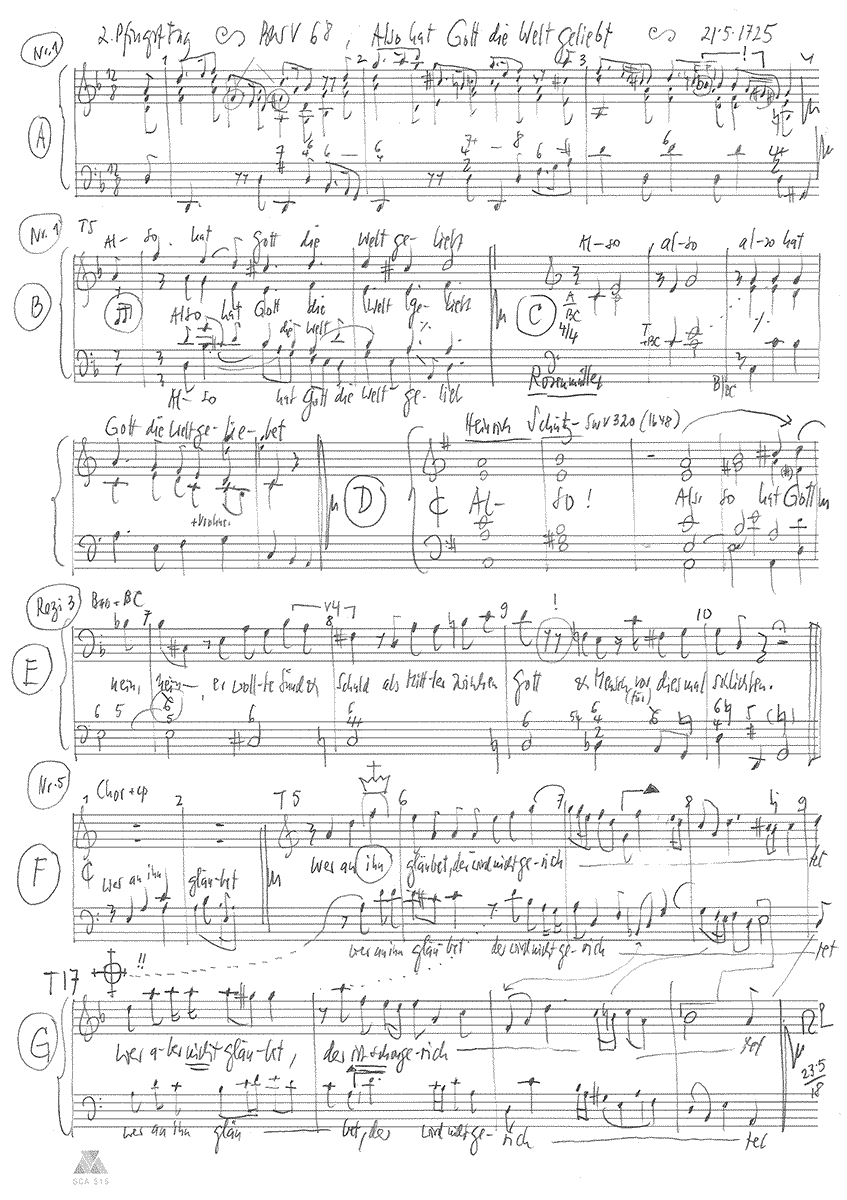

Cantata BWV 68, written for the Second Day of Pentecost in 1725, belongs to a group of sacred works that Bach composed in the period between Easter, when he suspended work on his chorale cantata cycle, and the First Sunday after Trinity, when he commenced his new annual cantata cycle. As with most libretti in this group of nine works, the poet Christiane Mariane von Ziegler links the Gospel of John with her own recitatives and arias. Nonetheless, because the biblical passage employed is a rhymed hymn verse by Salomon Liscov (1675), the cantata conforms to the same structure as the chorale cantatas of 1724/25.

The introductory chorus, a measured siciliano ritornello in 12⁄8 time, is a bittersweet “music of faith” that stresses the connection between Christ’s birth and crucifixion as well as faith and redemption. In this setting, the highly expressive gestures and abundant pre-imitations of the lower vocal parts lend additional support to the soprano melody (doubled by horn). In these sustained lines, restrained grandeur and muted sorrow meld as perfectly as the style alternates between choral aria and cantus-firmus motet.

After this weighty music of deliverance, the following F major aria setting appears all the more light and friendly. Indeed, some listeners may even detect a distinctly feminine tone in the soothing warmth and at times gallant style that exudes from the combination of joyous text, agile soprano lines and sonorous string cantilena. The second section, a trio with obbligato violin and oboe, evolves naturally from the flowing energy of the vocal aria; listeners unaware that this charming setting is a parody of a movement from Bach’s Hunt Cantata (1713) are unlikely to note the connection.

The following bass recitative, despite its brevity, is replete with momentous theological content. Although the opening reference to Peter’s contradictory reactions during the Passion of Christ is somewhat obscure, the noble-minded declaration and the exquisite modulation in the ensuing bars decidedly proclaim the joy to be found in the promise of Jesus and in his consoling presence as a mediator between God and humankind.

The gentle, reedy timbre of the ensuing bass aria with three oboes evokes pastoral associations that, in keeping with the overture-like style of the setting, serve as a reminder of the healing birth of the King of Heaven. In this movement, Bach successfully reworks Pan’s aria from the Hunt Cantata to realise a vocally brilliant and compositionally distinctive setting whose middle section skilfully illustrates both the shattering of the Earth and the faithful prayer that banishes all of Satan’s persuasion.

While Bach’s chorale cantatas generally conclude with a four-part chorale setting, Ziegler’s libretto, which ends with a further quotation from the Gospel (John 3:18), presents a totally different challenge for the composer: true to the Evangelist’s fundamental distinction between the faithful and the damned, the text juxtaposes two contradictory statements. This inspired Bach to compose an extended double fugue whose motet-like form and doubling with trombones and cornett evokes an archaic tone, thus imbuing the setting with an eschatological solemnity that even the chiselled cadences of the brilliant closing phrase fail to lift.

Libretto

1. Chor

Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt,

daß er uns seinen Sohn gegeben.

Wer sich im Glauben ihm ergibt,

der soll dort ewig bei ihm leben.

Wer glaubt, daß Jesus ihm geboren,

der bleibet ewig unverloren,

und ist kein Leid, das den betrübt,

den Gott und auch sein Jesus liebt.

2. Arie (Sopran)

Mein gläubiges Herze,

frohlocke, sing, scherze,

dein Jesus ist da!

Weg Jammer, weg Klagen,

ich will euch nur sagen:

Mein Jesus ist nah.

3. Rezitativ (Bass)

Ich bin mit Petro nicht vermessen,

was mich getrost und freudig macht,

daß mich mein Jesus nicht vergessen.

Er kam nicht nur, die Welt zu richten,

nein, nein, er wollte Sünd und Schuld

als Mittler zwischen Gott und Mensch vor diesmal schlichten.

4. Arie (Bass)

Du bist geboren mir zugute,

das glaub ich, mir ist wohl zumute,

weil du vor mich genung getan.

Das Rund der Erden mag gleich brechen,

will mir der Satan widersprechen,

so bet ich dich, mein Heiland, an.

5. Chor

»Wer an ihn gläubet, der wird nicht gerichtet;

wer aber nicht gläubet, der ist schon gerichtet;

denn er gläubet nicht an den Namen des

eingebornen Sohnes Gottes.«

Hans Magnus Enzensberger

The succinct defence of an agnostic

If someone were to get me to answer the Gretchen question – which is always a bit embarrassing – I would have little desire to do so. The closest I could come to getting out of it would be to claim that I am a Catholic agnostic.

That argument flies in the face of most rude questioners because it has something to do with a person’s background. It is the same with me.

My family comes from southern Germany, more precisely from the Allgäu. Apart from a few Roman, Celtic and Frankish touches, my ancestors were sedentary farmers. There were no varied immigrants such as Huguenots, Polish miners, Jewish peddlers or other refugees and displaced persons. The milieu was Alemannic and Catholic, but not Orthodox. On Fridays there was fish and wonderful casseroles on the table during Lent, but my parents couldn’t think of going to mass on Sunday on time. There was a Bible in the house, but it was rarely read.

Nevertheless, I was interested in theological questions as a pupil and as a student. This was thanks to the hospitality of the Benedictines in Neresheim, their table, their wine and their excellent library.

The small town in the Ostalb is famous for its abbey. This church is a magnificent baroque building designed by Balthasar Neumann. The seven times of the day from Matins to Compline were sung there in Latin and accompanied by the choir organ. The keeper of the library was a witty and accommodating man who also gave me all sorts of heretics to read: De rerum natura, the great doctrinal poem of Lucretius in the translation of Hermann Diels, the thoughts and opinions of Montaigne, Rameau’s nephew of Denis Diderot and similar things.

These authors did provide for my enlightenment; but the monastic brothers pointed out to me during the daily recreation after lunch that the medieval theologians dared to tackle the most delicate philosophical questions and debated them endlessly. Nominalism or realism, that was what the Scholastics’ universal dispute was about. What is the soul? What is the difference between faith and knowledge? Martin Luther called the teachings of scholasticism a “lying, accursed, diabolical babble”. The brothers of Neresheim did not agree with him.

The life that the astute and learned scholastics led was risky. They rode for weeks and months to get to Paris, Basel, Rotterdam or Oxford. The roads were besieged by soldateska and brigands. They could quote many writings of antiquity off the cuff. The Doctor angelicus was more authoritative than the Doctores subtilis, marianus and many others who were given such titles of honour. They mastered all the tricks of classical rhetoric. Buridan’s ass and Occam’s razor have remained proverbial to this day. Twentieth-century mathematicians, from Frege to Russell and Wittgenstein, admired scholars like William of Ockham and Duns Scotus, in whom they saw the founders of modern logic.

The conversations in the Neresheim monastery garden made a great impression on me at the time, even though I didn’t like much of the fathers’ woodsy church Latin. Besides, after the Second World War I was fixated on the German present. In the fifties, nobody wanted to know much about the crimes against humanity committed by the National Socialists. There was an obdurate silence about it. The old cadres were not prepared to give up their positions as judges, police chiefs and professors. Accordingly, it was tedious, exhausting and time-consuming to take on the task of rubbish collection in the political, economic and moral desert of the four-divided country.

This work was boring in the long run. For a minority of the younger ones, it threatened to become an obsessive occupation. There was a danger of self-righteousness. In the end, perhaps the thought that being a German was not a promising profession saved me from this. I preferred to write.

No one can get rid of the historical baggage that everyone, even a Swiss or a Swede, carries with them. We also carry part of this dowry and this burden around with us through religion.

A benevolent fairy godmother withheld from me the talent for believing in monotheism. The gods are so numerous that one is pained to choose. The Greek and Roman ones alone accompany us in the sky and in the days of the week, and the Egyptian and Asian traditions, from Tutankhamun and the Buddha, have never quite died out. Nor can a little Epicurus and a good dose of Stoa do any harm in my eyes.

For this reason alone, atheism is not an option for me, but a fixed idea. I do not want to belong to this club. In general, I find it difficult to decide to become a member. I lack the talent to be a reliable comrade. Of course, one can see a deficit in that.

So I have only one option. It is to be and remain an agnostic. The inventor of this term was an English biologist, Thomas Henry Huxley, a brilliant autodidact who was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society at the age of twenty-five. He was among the staunchest defenders of Darwin and his teachings.

The word agnostic, which is now also used in many other languages, was coined by Huxley in 1869. (Incidentally, the writer Aldous Huxley was his great-grandson. His famous novel about the future, Brave New World, is still thought-provoking today because it predicts that in future people will be bred in laboratories and prepared for a life as consumers without parents).

T. H. Huxley, of course, had no idea about modern genetics, cloning and the manipulation of the germ line. But he understood that Darwin’s opponents were united on one point. They truly thought they had more or less solved all the questions of human existence. “So they are convinced that they share in that gnosis¸ which was once a privilege of the Church. I, on the other hand, am not one of these initiates.”

The term may be of recent origin, but the attitude of the agnostic has a venerable past. The Greek word γνῶσις means knowledge, after all, and the sceptics formed a school of their own, beginning with Protagoras, who said of the gods: “Of them I am not able to ascertain, neither that they exist, nor that they do not exist, nor what form they take; for many things hinder a knowledge of them: the obscurity of the thing, and the brevity of human life.”

Pyrrhon of Elis, a Hellenistic sophist, made scepticism, that is, reflection and doubt, the central category of his philosophy. Opinions, he said, could be allowed, but certainty was unattainable. Sextus Empiricus, the last and most radical representative of this school, also denied the human ability to know what holds the world together at its core.

Thus, as an agnostic, one finds oneself in pretty good company. Many eighteenth-century thinkers belonged to this small club. David Hume and Denis Diderot can be counted among them. The Scottish philosopher is said to have told a story in Baron Holbach’s circle about the French missionaries who had invaded the primeval forests to convert the Canadian natives. One of these Hurons – as the Iroquois were then called – had been brought to London, where he was admitted to communion. “Now, my son, does not the grace of the sacrament work in you?” asked the priest. – “Yes,” replied the little Indian, “the wine does very well; but I think if I had been given brandy, that would have done me still better.”

Such jokes were common at Holbach’s table. Allegedly, the Baron asked the eighteen people present to vote on atheism. Fifteen are said to have voted in favour of atheism; the vote of the remaining three, including Diderot, has not survived. Presumably these were the agnostics. There is no documentary evidence for this gossip, which was circulated among the Enlightenment thinkers. It may be a lie, but at least it is well invented.

The attitude of the agnostic has all kinds of advantages and disadvantages. One can move more freely and does not have to submit to the hard and soft rules devised by any institutions. It can be a relief to throw off the respective party or church discipline. This is even more true for the shackles of a political ideology. The disadvantage is that the agnostic does not fully belong anywhere.

I would like to conclude these reflections with an anecdote recounted by an arch-Catholic friend of Pope John XXIII. One day, a scientist in Castel Gandolfo is said to have confessed to him that he was a pagan. The Pope replied that there were worse things; after all, his guest was un semi catolico.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).