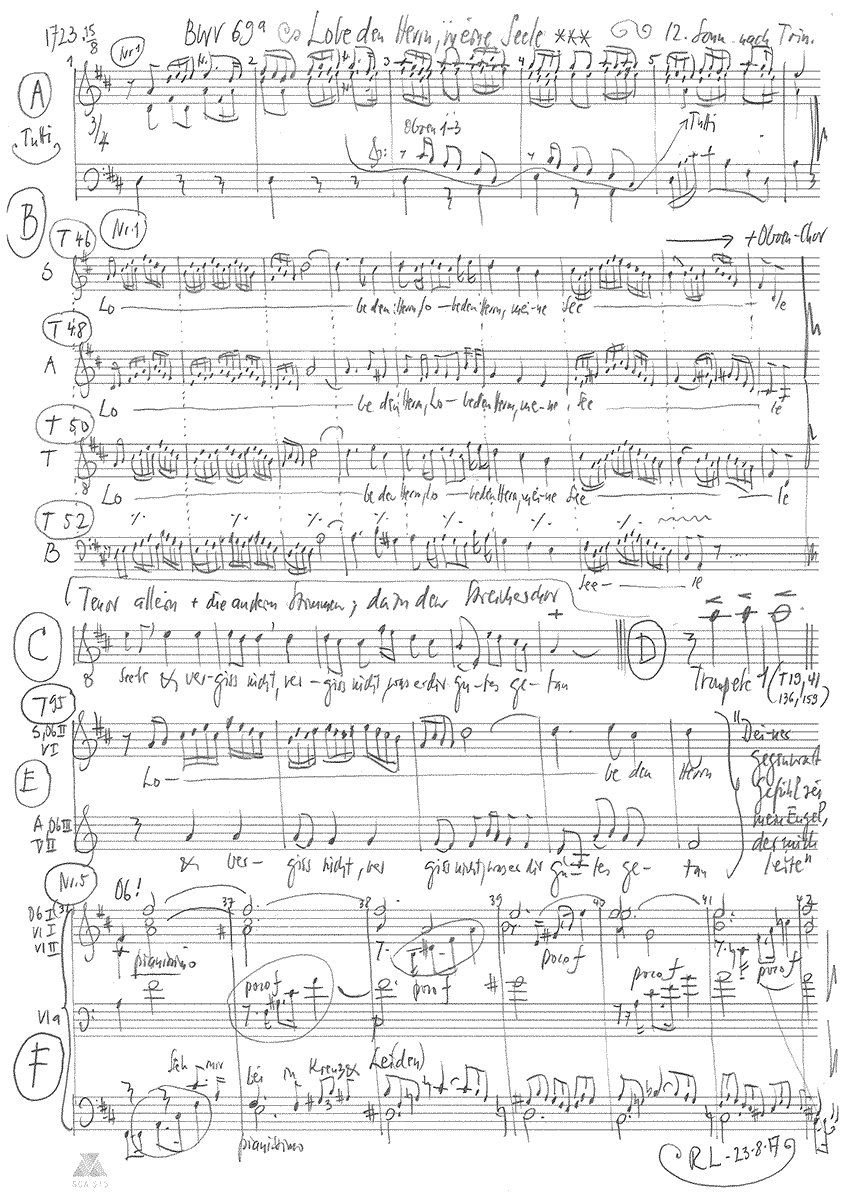

Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele

BWV 069a // For the Twelfth Sunday after Trinity

(Praise thou the Lord, O my spirit) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, flauto, oboe d’amore, oboe I-III, trumpet I-III, timpani, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Ich will den Herrn loben allezeit; sein Lob soll immerdar in meinem Munde sein. Meine Seele soll sich rühmen des Herrn, dass es die Elenden hören und sich freuen. Preiset mit mir den Herrn und lasst uns miteinander seinen Namen erhöhen. Da ich den Herrn suchte, antwortete er mir und errettete mich aus aller meiner Furcht. Welche auf ihn sehen, sie werden erquickt, und ihr Angesicht wird nicht zu Schanden. – Schmecket und sehet, wie freundlich der Herr ist. Wohl dem, der auf ihn traut!

Ein solch Vertrauen aber haben wir durch Christum zu Gott. Nicht, dass wir tüchtig sind von uns selber, etwas zu denken als von uns selber; sondern dass wir tüchtig sind, ist von Gott, welcher auch uns tüchtig gemacht hat, das Amt zu führen des Neuen Testaments, nicht des Buchstabens, sondern des Geistes. Denn der Buchstabe tötet, aber der Geist macht lebendig. So aber das Amt, das durch die Buchstaben tötet und in die Steine gebildet war, Klarheit hatte, also dass die Kinder Israel nicht konnten ansehen das Angesicht Moses um der Klarheit willen seines Angesichtes, die doch aufhört, wie sollte nicht viel mehr das Amt, das den Geist gibt, Klarheit haben! Denn so das Amt, das die Verdammnis predigt, Klarheit hat, wie viel mehr hat das Amt, das die Gerechtigkeit predigt, überschwängliche Klarheit. Denn auch jenes Teil, das verklärt war, ist nicht für Klarheit zu achten gegen diese überschwängliche Klarheit. Denn so das Klarheit hatte, das da aufhört, wie viel mehr wird das Klarheit haben, das da bleibt.

Und da er wieder ausging aus der Gegend von Tyrus und Sidon, kam er an das galiläische Meer, mitten in das Gebiet der Zehn Städte. Und sie brachten zu ihm einen Tauben, der stumm war, und sie baten ihn, dass er die Hand auf ihn legte. Und er nahm ihn von dem Volk besonders und legte ihm die Finger in die Ohren und spützte und rührte seine Zunge und sah auf gen Himmel, seufzte und sprach zu ihm: «Hephatha!» Das ist: Tu dich auf! Und alsbald taten sich seine Ohren auf, und das Band seiner Zunge ward los, und er redete recht. Und er verbot ihnen, sie sollten’s niemand sagen. Je mehr er aber verbot, je mehr sie es ausbreiteten. Und sie wunderten sich über die Massen und sprachen: «Er hat alles wohl gemacht; die Tauben macht er hörend und die Sprachlosen redend.»

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Anna Walker, Maria Weber

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Lea Pfister Scherer, Alexandra Rawohl, Damaris Rickhaus

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Raphael Höhn, Christian Rathgeber, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Oliver Rudin, Tobias Wicky, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Claire Foltzer, Elisabeth Kohler, Marita Seeger, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Martina Zimmermann

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Philipp Wagner, Natalia Herden

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Lukas Gothszalk, Bruno Fernandes, Alexander Samawicz

Recorder/Flute

Annina Stahlberger

Timpani

Reto Baumann

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Rita Famos

Recording & editing

Recording date

25.08.2017

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Johann Oswald Knauer, 1720/21

Text No. 1

Psalm 103:2

Text No. 6

Samuel Rodigast, 1675

First performance

15 August 1723

In-depth analysis

Cantata BWV 69a, first performed on the Twelfth Sunday after Trinity in 1723, numbers among those compositions written during Bach’s first months in Leipzig that served to assert the new Thomascantor’s ambitions as Kapellmeister. With its laudatory style and brilliant sound, the cantata was no ordinary Sunday music, and it is unsurprising that Bach later reworked it after 1740 as a festive cantata for the annual council elections. The introductory chorus is set as an expansive, four-ensemble concerto on the well-known psalm verse “Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele” (Praise thou the Lord, O my spirit); the scoring for three trumpets and timpani, three oboes and bassoon, a string ensemble and a four-part choir lend the movement considerable brilliance. Despite this full orchestration, however, the instrumental overture is feather-light and transparent in sound; the vocal ensemble, too, opens with pairings of soloistic, coloratura phrases that embody relaxed rejoicing more than ceremonial chanting. After this opening section, the four voices briefly come together before commencing a broad vocal fugue that is successively enhanced by instrumental entries; a crowning tutti-passage then leads directly into a second, more introspective fugue, whose gently sighing, descending theme is set to the text of “und vergiss nicht” (and do not forget). The compositional quality of this setting is stellar: Bach delicately interweaves the various ensemble lines while nonetheless showcasing their individual timbres, and despite the complexities of the setting, the underlying motif “Praise the Lord” is sustained throughout. In view of this stylistic mastery, it seems almost a matter of course that the two related fugue themes are then presented simultaneously, with compositional scope still remaining for declaratory calling phrases and a closing orchestral da-capo section. That three brief passages of parallel unisons in neighbouring voices are to be found among the racing machinery of this setting, has, however, not escaped the notice of the odd compositional pedant.

In the following soprano recitative, a setting suffused with inspired gratitude and ecclesiastical love, the enraptured vocalist wishes for “tausend Zungen” (one-thousand tongues) to praise God and to never again to use a mouth thus purified to utter “eitle Worte” (empty words). In the following tenor aria, this mysteriously transformed speech takes on concrete form: in a gently rocking 9⁄8-setting, Bach employs an unusual timbral combination of recorder and oboe da caccia, thus uniting blissful innocence with a gnarly warmth to realise a music that radiates an inner joy rarely granted to mere mortals. “Meine Seele, auf, erzähle, was dir Gott erwiesen hat” (O my spirit, rise and tell it, all that God hath shown to thee) – with these words, set to a nobly heroic head motif, the act of singing from “frohen Lippen” (joyful lips) becomes itself a sacrifice of thanksgiving; that Bach’s inspired combination of timbres possibly failed to achieve the intended effect in the 1723 performance might explain why he used a more typical combination of violin and oboe when later reworking the movement around 1727.

In the following contemplative recitative, the alto reflects on the many blessings received from God “von zarter Jugend an” (from tender childhood on). Although we humans are inherently incapable of adequately returning God’s love, the proximity of the Highest helps to overcome this failing. Because the librettist deftly weaves in the gospel story of the deaf and mute man (Mark 7:31) who is healed when Jesus cries “Hephata!” (Be opened!), the proclaiming mouth and the listening ear, too, are incorporated in this laudatory music. Performers and listeners alike thus become party to this purification, and the gently flowing arioso finale transforms the old Bible verse into an inspiring resolution to lead a good life.

After this display of humility, the aria exemplifies how strength can be drawn from experiencing divine love and protection. Set in minuet style with edgy dotted rhythms, the music, despite its muted key of B minor, anticipates a favourable response to the soloist’s request of “Mein Erlöser und Erhalter, nimm mich stets in deine Hut” (My redeemer and sustainer, keep me in thy care and watch). Here, an enlightened and self-assured soul steps into the ring, who, fully aware of the challenges of “Kreuz und Leiden” (cross and suffering) that lie ahead, is confident of persevering thanks to God’s righteous plan. In this setting, the string ensemble is enhanced by the warmth of the oboe d’amore; for the grounded, defiant nature of the solo part, only a sonorous bass will suffice.

For the closing chorale, an energetic setting in G minor, Bach revived a cantional setting from an earlier Weimar cantata, “Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen” (weeping, wailing, grieving, fearing; BWV 12, 1714), which, despite its low register, exudes an aura of serene hope. It is not known why Bach removed the original obbligato part (which was probably for violin); when he revised the cantata again for the council elections (BWV 69), he selected another chorale entirely and included trumpets and timpani.

Libretto

1. Chor

»Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele, und vergiß nicht,

was er dir Gutes getan hat.«

2. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Ach, daß ich tausend Zungen hätte!

Ach wäre doch mein Mund

von eitlen Worten leer!

Ach, daß ich gar nichts redte,

als was zu Gottes Lob gerichtet wär!

So machte ich des Höchsten Güte kund;

denn er hat lebenslang so viel an mir getan,

daß ich in Ewigkeit ihm nicht verdanken kann.

3. Arie (Tenor)

Meine Seele,

auf, erzähle,

was dir Gott erwiesen hat!

Rühme seine Wundertat,

laß ein Gott gefällig Singen

durch die frohen Lippen dringen!

4. Rezitativ (Alt)

Gedenk ich nur zurück,

was du, mein Gott, von zarter Jugend an

bis diesen Augenblick

an mir getan,

so kann ich deine Wunder, Herr,

so wenig als die Sterne zählen.

Vor deine Huld, die du an meiner Seelen

noch alle Stunden tust,

indem du nie von deiner Liebe ruhst,

vermag ich nicht vollkommen Dank zu weihn.

Mein Mund ist schwach, die Zunge stumm

zu deinem Preis und Ruhm.

Ach sei mir nah

und sprich dein kräftig Hephata,

so wird mein Mund voll Dankens sein!

5. Arie (Bass)

Mein Erlöser und Erhalter,

nimm mich stets in Hut und Wacht!

Steh mir bei in Kreuz und Leiden,

alsdenn singt mein Mund mit Freuden,

Gott hat alles wohl gemacht.

6. Choral

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

darbei will ich verbleiben.

Es mag mich auf die rauhe Bahn

Not, Tod und Elend treiben:

so wird Gott mich

ganz väterlich

in seinen Armen halten.

Drum laß ich ihn nur walten.

Rita Famos

On the power of praising God

The cantata “Lobe den Herrn meine Seele” (BWV 69a) gives thought to the basic principles of Christian spirituality: Christians do not found their lives on their own. They owe it to God, and they express this fact in praise of their Creator. Faith is transmitted in particular through language. It is the stories of successful life that give Christians strength to believe and live.

“This music lifts me up, glows through me and infects me with its optimistic profundity,” says John Elliot Gardiner about Bach’s music in an interview with the German weekly DIE ZEIT. Something of this glow and optimistic profundity shines forth in the cantata Lobe den Herrn meine Seele. I at least feel strengthened, encouraged but also comforted every time I hear it. The music speaks for itself, independent of the text, and has the power to take me into a state of gratitude and confidence.

But even when the music speaks without words, Gardiner says in another place, “If you are not at least rudimentarily familiar with the religious ideas that animate this music, you can miss many nuances.” In this reflection, I want to follow one of these central “religious ideas”. It underlies the cantata and is: “In the praise of God there is a life-shaping power”.

Thank you…

Praise the Lord my soul. The title of the cantata BWV 69a already thematises the praise of God. However, the intention to praise God is implicit in Bach’s entire work. “Soli Deo Gloria” we read under every musical work by Johann Sebastian Bach as a personal signature. No matter whether the work deals with suffering, guilt, death or is purely instrumental. “Soli Deo Gloria – To the glory of God alone” it is meant to serve. Music has the function of praising God and reflecting the wonders of life, according to the basic conviction already expressed by the reformer Martin Luther and which lies behind Bach’s work. Bach thus expresses that he always wants to point beyond himself. To another origin, to another, a greater power. And with the abbreviation “SDG” he expresses that his creative work connects him with the creative creative power of God, which he senses as the primal ground beneath all being.

With the ancient biblical words, the cantata BWV 69a encourages us listeners to join in the praise of God and express our gratitude to God. At first, gratitude is not bound to a recognisable reason. It is a general gratitude towards life.

This gratitude towards existence and the miracle of life is felt by everyone, whether religious or not. It takes hold of us, for example, during experiences of nature: when the first ray of sunlight caresses our face in the morning, when the spray electrifies our skin, when the clear starry night directs our gaze into the universe. It overwhelms us at the birth of a child, which we can explain biologically, but which nevertheless leaves us in awe-struck wonder. We become grateful simply because we are there, because we are allowed to share in the uniqueness of life.

Religious people give these feelings an address. They express their gratitude to the Creator God. For two millennia, the liturgies of all Christian denominations have contained the element of praise to God as a fixed component. Regardless of the very concrete situation in life, at the beginning of the prayer of the day or the service, the gaze is turned away from one’s own existence towards God. Man acknowledges before his Creator that he does not exist by his own strength, that his life is an undeserved gift. Christian worship has institutionalised this grateful turning towards the source of being. It has thus become a kind of spiritual exercise that is rhythmically implanted in the lives of practising Christians. Regularly becoming aware that human beings do not create their own lives is a genuine part of Christian spirituality.

The individual believer is certainly not always in the mood to devote himself to this praise of God. For the natural impulse of man is rather to constantly keep the dangers, risks and problems before his eyes in order to develop coping strategies in time. This impulse is certainly an important strategy that ensures the further development and survival of the human race. But the Christian liturgy, with its praise of God, puts a complement to this anxious impulse. Looking away from the dangers and problems towards God and his creative, creative power creates a healthy distance and relieving humility: Man does not have to master life or even improve the world by his own strength alone. There is God, who created the world and whose creative power continues to work in all life. That relieves, that comforts, that encourages. At the same time, the individual believer, even if often not in the mood for gratitude, allows himself to be carried and inspired by the community, which repeats the old songs and prayers.

… and tell!

Now, however, both the cantata text and the psalm text on which it is based go a step further. “Praise the Lord, my soul, and forget not what good he has done for you.” The tenor aria takes up this encouragement to remember with gratitude by also announcing the method of remembering while singing: “My soul, up, tell!”

There is great power in telling the stories in which life has succeeded. The biblical tradition is narrative. It passes down many stories of how people, with God’s help, have succeeded in life from generation to generation. And the biblical tradition calls on us to do the same as individuals in the community: tell stories of how you have mastered life. Don’t forget all the good things that have already happened to you.

Victor Frankl, the Jewish doctor and psychotherapist, founder of logotherapy, describes his experiences in the Auschwitz concentration camp during the Second World War in his well-known work “…and yet say yes to life”. One story has left a lasting impression on my memory: Frankl tells of a day when he and his fellow sufferers were already very depressed when suddenly the electricity failed. Hopeless and completely exhausted, the tortured lay on their cots in the dark barracks. Then Frankl was asked by the block elder to speak to his fellow prisoners. And although he did not feel like it, he raised his voice. He spoke of the uncertainty of the future. “But,” Frankl continued, “I spoke not only of the future and of the darkness in which it was shrouded, and of the present with all its sufferings, but I also spoke of the past – of all its joys and the light it still gave into the darkness of our days. I quoted the poet who says: ‘What you have experienced, no power in the world can rob you of’. What we have realised in the fullness of our past life, in its wealth of experience, nothing and no one can take away from us this inner richness. But not only what we have experienced, what we have done, what we have ever thought great things, and what we have suffered (…) all this we have saved into reality, once and for all. And even if it has passed – it is secured in the past for all eternity! For being past is also a kind of being, yes, perhaps the most secure.”

Frankl then goes on to speak of the possibility of filling every situation, life, with meaning, and concludes by describing the effect of what he considers his modest attempt to cheer up his fellow prisoners. “Soon the electric bulb on a beam of our barrack flared up again, and I saw the wretched figures of my comrades, who now hobbled up to my place with tears in their eyes to – thank me…”

This unforgettable account of a day in Auschwitz is a testament to the power that lies in recounting life’s bright moments. The telling of powerful moments takes people out of the paralysing present and transports them to the moment when they felt vibrancy and vitality, when they created life, when they felt joy. Storytelling brings the energy contained in those moments into the present and takes people out of the trance into which worries, fears and anguish can entangle them. Through storytelling, people can connect with their possibilities and the potential that is within them, even though it is not available to them at the moment.

Most of the time this does not happen spontaneously. The problems of the present are naturally closer to us than the success stories and moments of happiness of the past. That is why we need a friend, a pastor or a therapist from time to time to gently take us by the hand and lead us to the lighter moments in our life story. The cantata Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele can also take on this pastoral role. Its powerful music with its clear invitation reminds us to be grateful for the miracle of life in which we are allowed to participate. Listening to the lilting sounds, we are invited to gratefully visualise successful moments in our lives. Should life throw us onto the “rough track”, thanksgiving and recounting memories will strengthen us.

Literature

– John Eliot Gardiner, Bach – Music for a Castle in the Sky, Hanser, Munich 2016

– John Eliot Gardiner, “This music glows through me”, interview in: DIE ZEIT, 8 December 2016

– Victor Frankl, “… and still say yes to life”, Kösel, Munich 3rd edition 2012

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).