Herr, wie du willt, so schick’s mit mir

BWV 073 // For the Third Sunday after Epiphany

(Lord, as thou wilt, so deal with me) for soprano, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, horn, bassoon, strings and continuo

Cantata BWV 73 “Herr, wie du willt, so schick’s mit mir” (Lord, as thou willt, so deal with me) belongs to Bach’s first Leipzig cantata cycle and was first performed in the Nikolaikirche on 23 January 1724. With its brief but highly expressive forms, it is reminiscent of a finely drawn miniature.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Noëmi Sohn

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Lea Scherer, Katharina Jud

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Valentin Parli, Chasper Mani

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Fanny Tschanz

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Martin Stadler, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Horn

Olivier Picon

Organ

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Angelika Overath

Recording & editing

Recording date

01/21/2011

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Poet unknown

Text No. 1

Interpolated chorale lines by Kaspar Bienemann, 1582

Text No. 5

Ludwig Helmbold, 1563

First performance

Third Sunday after Trinity,

23 January 1724

In-depth analysis

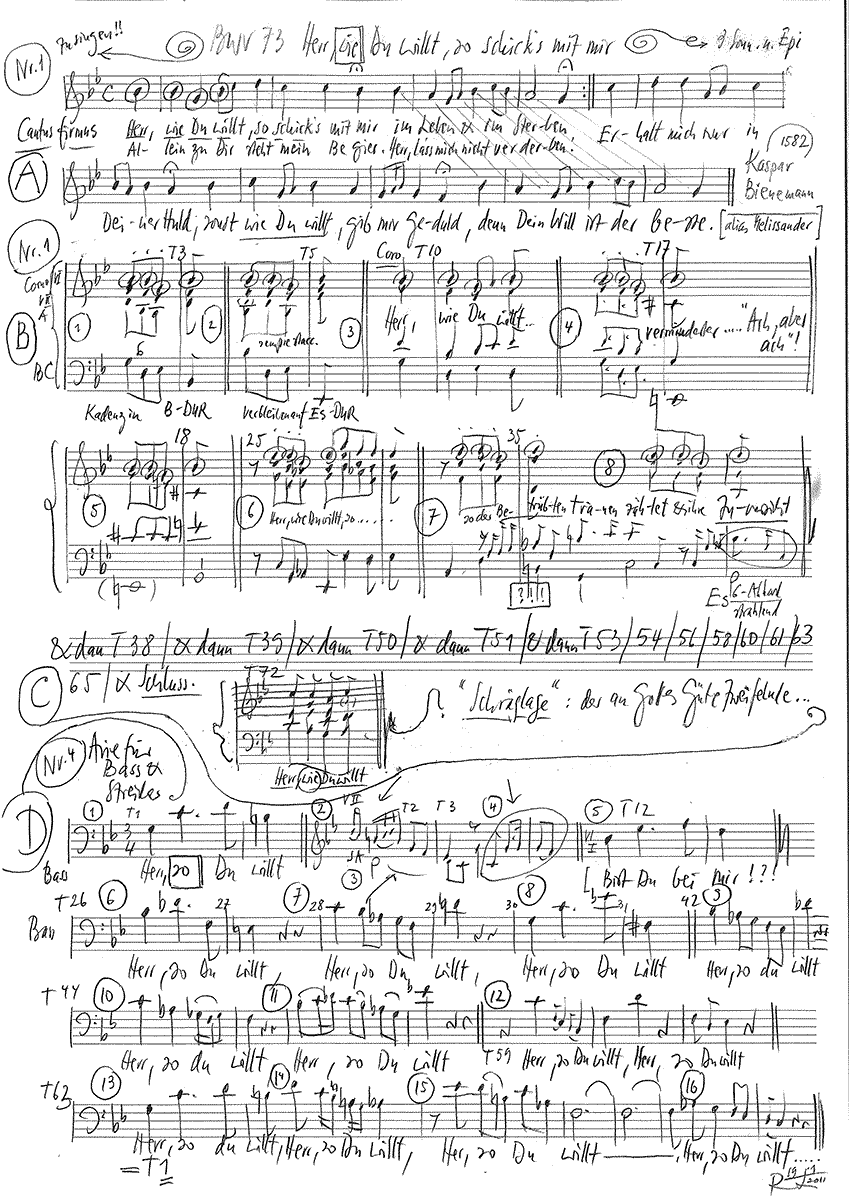

The introductory chorale commences with a consistently repeated four-note sequence in the instrumental parts, an aphoristic leitmotif that reflects the words “Lord, as thou willt”. Indeed, this religious dictate seems to be literally hammered in by the staccato style of the orchestral material as well as the horn part (which was replaced in a later version by an “Organo obbligato”). The exacting character of the movement is counterbalanced solely by the two oboes whose soothing sequences in thirds alleviate somewhat the rigidity of the divine command. The following vocal section applies a troping technique. Here, each section of choir text sung to the melody of “Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns halt” by Kaspar Bienemann (1582) is superseded by a vocal solo that applies the chorale’s “objective” message to the timeless struggles and conflicts of earthly existence. In these tenor, bass and soprano passages, the gradual transformation from doubt in God’s promise and the purpose of human suffering to a pronouncement of trust and hope is achieved with particular textual and musical skill.

In the following aria trio “Ah, pour thou yet thy joyful spirit”, the tenor, supported by a simple continuo accompaniment, continues the elegantly flowing melody introduced by the oboe. Despite its rich coloraturas, the restrained gesture of the music, the sigh of the middle section and the somewhat wistful E-flat major tonality suggest that the true heart of the matter is not earthly pleasure, but the serenity found in acceptance of humankind’s inevitable lot.

Commencing with an abrupt modulation and exclamatory “Ah!”, the following bass recitative captures the faltering nature of the human will, interpreted musically by inverting the seventh between the continuo and voice on the word “perverse”. With its seamless transition to the following aria, the recitative becomes part of a larger, unique musical structure. This freely contrapuntal movement commences with no less than 16 repetitions of the dictum “Lord, as thou willt”, offering a poignant and emotional interpretation of the Christian readiness to die and of victory over death. With its sighs and dynamic contrasts, this section is extraordinarily rich in affect. Indeed, in the bass cantilena, the soloist – accompanied by pizzicato strings – seems almost to be singing his own requiem. With this devout swan song, Bach creates a musical portrayal of surrender to God’s will that has doubtlessly comforted many a listener – both in Bach’s day and ours. In its simplicity and restraint, the closing chorale “This is the Father’s purpose” offers a moment of exquisite tenderness and consolation.

Libretto

1. [Choral und Rezitativ] (Tenor, Bass, Sopran)

Herr, wie du willt, so schick’s mit mir

im Leben und im Sterben!

(tenor)

Ach! aber ach! wieviel

lässt mich dein Wille leiden!

Mein Leben ist des Unglücks Ziel,

da Jammer und Verdruss

mich lebend foltern muss,

und kaum will meine Not im Sterben von mir scheiden.

Allein zu dir steht mein Begier,

Herr, lass mich nicht verderben!

(bass)

Du bist mein Helfer, Trost und Hort,

so der Betrübten Tränen zählet,

und ihre Zuversicht,

das schwache Rohr, nicht gar zerbricht;

und weil du mich erwählet,

so sprich ein Trost- und Freudenwort.

Erhalt mich nur in deiner Huld,

sonst wie du willt, gib mir Geduld,

denn dein Will ist der beste.

(sopran)

Dein Wille zwar ist ein versiegelt Buch,

da Menschenweisheit nichts vernimmt.

Der Segen scheint uns oft ein Fluch,

die Züchtigung ergrimmte Strafe,

die Ruhe, so du in dem Todesschlafe

uns einst bestimmt,

ein Eingang zu der Hölle.

Doch macht dein Geist uns dieses Irrtums frei,

und zeigt, dass uns dein Wille heilsam sei.

Herr, wie du willt!

2. Arie (Tenor)

Ach senke doch den Geist der Freuden dem Herzen ein.

Es will oft bei mir geistlich Kranken

die Freudigkeit und Hoffnung wanken

und zaghaft sein.

3. Rezitativ (Bass)

Ach, unser Wille bleibt verkehrt,

bald trotzig, bald verzagt,

des Sterbens will er nie gedenken!

Alkein ein Christ, in Gottes Geist gelehrt,

lernt sich in Gottes Willen senken,

und sagt:

4. Arie (Bass)

Herr, so du willt,

so presst, ihr Todesschmerzen,

die Seufzer aus dem Herzen,

wenn mein Gebet nur vor dir gilt.

Herr, so du willt,

so lege meine Glieder

in Staub und Asche nieder,

dies höchst verderbte Sündenbild.

Herr, so du willt,

so schlagt, ihr Leichenglokken,

ich folge unerschrokken,

mein Jammer ist nunmehr gestillt.

Herr, so du willt.

5. Choral

Das ist des Vaters Wille,

der uns erschaffen hat;

sein Sohn hat Guts die Fülle

erworben und Genad;

auch Gott der Heilge Geist,

im Glauben uns regieret,

zum Reich des Himmels führet:

ihm sei Lob, Ehr und Preis.

Angelika Overath

“It is now the music that wants”.

Bach at the turn of autonomous art.

What a strangely strange and close phrase: “Lord, as thou wilt, so send it with me, / in living and in dying!” The text of the cantata BWV 73 is 429 years old. It comes from a time when the Reformation was still very young. And the pastor and poet Kaspar Bienemann (almost a contemporary of Luther) was already on difficult ground with his song. What is the freedom of a Christian man? What can the human will do? Can the individual move towards God so that his energy of faith comes together with the grace of a benevolent ruler? Does he – creature of a higher power – in his surrender to that which transcends him, have the small chance to influence his salvation? Or is he exclusively dependent on an incomprehensible grace that chooses him – or does not choose him?

In Kaspar Bienemann’s song, at any rate, an I speaks directly to a Thou. In an act of absolute trust, this I surrenders its entire existence to this other.

“Herr, wie du willt, so schick’s mit mir” is Kaspar Bienemann’s best-known song; it is still found today as No. 367 in the Evangelical Hymnal. Bach’s cantata, which begins quoting this old chorale, was first performed in Leipzig on 23 January 1724. In the same year, only a few winter weeks, a few spring weeks later, a boy was born in Königsberg on 22 April who was to change European intellectual history. With Immanuel Kant, Western thought experienced the definitive turn towards self-determination. From now on, the focus of human existence was no longer God, but the autonomous subject. While Kant did not categorically exclude God, he no longer necessarily included him. God had become a form of possibility: “The ground of proof of the existence of God that we give is merely built on the fact that something is possible.” For the first time, man saw himself under an open firmament and was responsible for his actions before himself and other men (but not before God). “Two things fill the mind with ever newer and more to be taken admiration and awe, the more often and persistently the reflection is occupied with them: The starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.”

Today we are children of the Enlightenment. We have learned to use our minds. We are willers. The future is to be achieved; we like to see ourselves as the victors of our existence. Failure, that would be a luxury we cannot afford. So what do we do with a sentence like this: “Lord, as you will, so send it with me”? These words turn every striving principle of success upside down. They undermine free will, they throw the subject back into the bondage of a You to whom it grants unrestricted authority over itself.

I listen to the Bach cantata not as a believer. But as someone who marvels. In this text, in this music, something happens that touches me, independent of any Christian message of faith. I wonder what that is. Probably it has to do with a tension between wanting and allowing, freedom and humility, I and you.

I’ll try to describe it.

The first impression is solemn serenity. An unknown poet lets three subjective voices speak into the old chorale with tenor, bass and soprano. After the choral entrance quotes the unbroken confidence in God, a personal, contradictory lament first begins with the tenor voice:

“Ach! aber ach!” in a few words a person is outlined who finds himself in an utterly hopeless situation. Life is torture for him and the prospect of death promises no relief (“hardly will my misery depart from me in death”). One cannot be worse off.

The chorus strides over this hopelessness as if unmoved with all the power of the old song. To which the poet allows a balancing bass voice to respond, mediating between the despair and the choir’s certainty of faith by speaking of confidence.

And the choir, like a basso continuo of strength of faith, then sings its final lines of the stanza, which unquestioningly place the will of God above all else.

Seraphically, as the third solo voice, the soprano now reflects the insufficient possibilities of human knowledge. God’s will remains a sealed book. Man is in a constant state of misunderstanding vis-à-vis God. What was meant as the rest of the sleep of death, he fears as the entrance to hell. (Death as Sleep’s Brother, which the poet quotes here, is in an ancient, not a biblical tradition).

Man does not understand his life and death; it is only the Spirit of God who can show him what would be good for him.

The collage ensemble (of old chorale and new role voices) is now concluded with a threefold “Lord, as you will”. This text motif, as well as its musical counterpart, which plays around and connects the entire first part, will not appear again in the continuation of the cantata.

But in what does the spirit of God promised by the soprano voice consist, which shows what is salutary for man?

As if it were or as if it contained the answer, a tenor aria follows, which deals with the “spirit of joys”. Purely logically, from the sense of the words, the tenor voice invites God to lower the spirit of joys into the heart of man. In fact, however, this singing evokes exactly what it asks for. It allows joy to be present. The very short text, painting melodies, repeating words (until they dissolve into sounds), is sung widely and playfully, in ever new coloraturas and approaches, until, onomatopoeically, the singing seems to sing itself. And the “spiritually ill” falls into a fluid of redemptive cheerfulness.

The musical figures of “joy” and “wavering” correspond with each other, indeed the “wavering” becomes musically a syncopated sovereign play with uncertainty. This wavering is meticulously calculated voice leading and of the sure lightness of a natural dance, as it were.

In the Grimm dictionary, the word “Freude” is also listed as a synonym of “spiel und lied”. Making joy was still a term for “playing music” for a long time. This would mean that the divine spirit of joys was making music and the spiritually ill person was also the one who lacked singing, playing. Even David played the harp before the melancholy Saul. It was the only means of driving away the “evil spirit”.

A short bass recitative now takes up the movement of the sinking as a mirror figure. Just as God’s “spirit of joy” was to sink into the heart of man, so man is now called to sink into “God’s will”. This bass recitative leads directly into the bass aria.

And from now on, the will motif changes both textually and musically. Instead of Bienemann’s line “Lord, as you will”, the call to healing from the Gospel of Matthew appears: “Lord, if you will” (“Lord, if you will, you can cleanse me”). Instead of “as” now “so”.

The three stanzas of the unknown author also begin with “so”: “so press ye pains of death”, “so lay my limbs” and “so strike, ye funeral bells”. The conditional “so”, in the sense of “if” (Lord, if you will, you can purify me), is played around with the consecutive “so” of the sequence: “So then”. So then it shall be.

This aria is about the willingness to die without fear.

“Mein Jammer ist nunmehr gestillt” are the concluding words written by the poet for the cantata’s last subjective voice. They stand in direct contrast to the despair of the initial tenor voice, for whom there was no redemption even in death. So what has happened? Why is the lamentation now satisfied?

Again and again it was pointed out in commentaries that the quoted passage from the Gospel of Matthew was about healing and that here it was not about healing but about dying. But perhaps one can see it differently. At any rate, I hear it differently. In this varying, free music-making around the spirit of joy, I already hear a healing, a healing from fear, from the pain of life, a healing through music.

Up to the final line, “My lament is now satisfied”, the will motif “Lord, if you will” can be heard a total of nine times. After that, however, it culminates in a further six musical variations at the end. A tremendous singing out takes place here. It is now the music that wants.

And I hear, after all the “so” variations that shimmer between conditional, modal and consecutive, I hear, in addition to “Lord, as you will”, “Lord, so you will”, also a “Lord, so you will!”. Lord, you want this music-making, this joy. And this music is my prayer before you.

To the You of God the Father at the beginning of the cantata, who is to guide man’s destiny completely and utterly: “Lord, as you will”, to the You of the Son of God, who is to purifyingly heal, “Lord, as you will”, there would then come at the very end the You, the counterpart of the music. It alleviates the fear of life as well as the fear of death.

Because there is this You of music, religious musical art can also take away something of the burden of the modern self. And it almost seems to me that the composer sensed something of this new, dangerous freedom of an autonomy of art at the turn of the Enlightenment. With the simple golden seal of a chorale, again from the 16th century, he certainly closes this cantata. The chorale (by Ludwig Helmbold, a philosophy professor, pastor and hymn writer) is a radiantly unbroken praise of the divine Trinity.

“Lord, as thou wilt, so send it with me, / in living and in dying” – this strange line from the time of the Reformation has an echo for me in a Hölderlin verse that is about the necessary experience of suffering, fear, divisiveness:

“Let man try everything, say the heavenly ones,

That he, strongly nourished, may learn to give thanks for everything,

(…).”

The verse is taken from the ode “Lebenslauf”, a poem that Hölderlin wrote after experiencing the loss of love. At the beginning, there is the image of the arc of life of man, which strives upwards and, after the experience of suffering, bends, is bent backwards. But it is only in this bend of pain that the arc of life has the tension for the arrow (of freedom, creativity, art) that reaches further than it could alone.

Curriculum vitae

You too wanted greater things,

But love forces us all down,

Suffering bows more mightily,

But it does not return in vain

Our bow, whence it comes.

Up or down! Reign in holy night,

where dumb nature ponders the days to come,

Reigns in the crookedest gloom

not one degree, one right too?

This I have learned. For never, like mortal masters,

Have you celestials, you all-sustaining,

That I might know with care

Led me along the level path.

Let man test everything, say the celestials,

That he, well nourished, may learn to give thanks for all,

And understand the freedom

To go where he will.

Not in the words of the chorale, but in Bach’s musical realisation, I hear something of this freedom that owes itself to the humility of the experience of sorrow. One can understand from this Hölderlinian final stanza how short-sighted the strict opposition of unconditional surrender to the will of God and modern perfect self-determination is. We have the freedom to set out wherever we want, but the gift of freedom is something that we, creatures of an unrecognised power, do not owe to ourselves. It was given to us.

Whether it is the Christian God, the image of the ancient gods, the cosmic nature of the starry sky or the You of art, there is an immense relief in the consenting movement towards a counterpart that transcends us.

We are not in control of our lives. We are far from being masters of nature. And without modesty we will not get anywhere in art either. Despite all our safe craftsmanship, we remain dependent on the epiphany, the decisive moment, the moment when the personal self becomes unimportant and something happens that eludes our practical will for an eternal second.

For me, one of these moments (in this cantata) is the moment when, in the final aria at the beginning of the last verse, the pizzicato begins at the third “willt”, and the coming, body-heavy word of the “Leichenglocken” (funeral bells) dances along with the intrepid and already self-forgetful journey of a helplessly upright self.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).