Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten

BWV 074 // For Pentecost (Whitsunday)

(He who loves me will keep my commandments) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I-III, timpani, oboe I+II, oboe da caccia, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Alice Borciani, Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Simone Schwark, Linda Loosli, Lia Andres, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Jan Thomer, Antonia Frey, Laura Binggeli, Lea Scherer, Alexandra Rawohl

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Klemens Mölkner, Manuel Gerber, Christian Rathgeber

Bass

Philippe Rayot, Julian Redlin, Daniel Pérez, Simón Millán, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó, Aliza Vicente

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Jakob Valentin Herzog

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Philipp Wagner

Oboe da caccia

Andreas Helm, Clara Espinosa Encinas

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Klaus Pfeiffer

Timpani

Martin Homann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Kerstin Wiese

Recording & editing

Recording date

26/05/2023

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

20 May 1725, Leipzig

Text sources

John 14:23 (movement 1); Christiane Mariane von Ziegler (movements 2–3, 5, 7); John 14:28 (movement 4); Romans 8:1 (movement 6); Paul Gerhardt (movement 8)

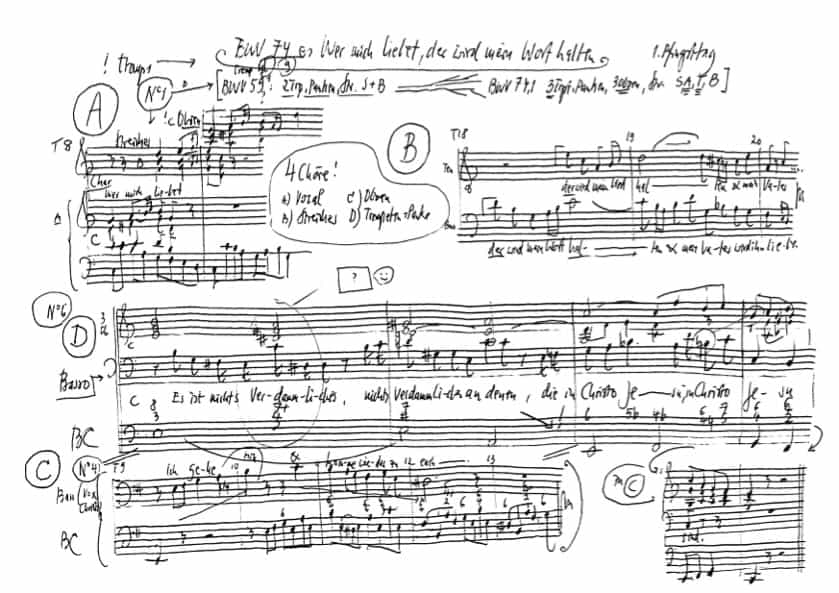

In-depth analysis

The cantata “Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten” (He who loves me will keep my commandments, BWV 74) in many ways offers a glimpse into the Thomas cantor’s compositional workshop. Written for Whitsunday in 1725 as part of a mini-cycle of nine cantatas set to libretti by the Leipzig poet Christiane Mariane von Ziegler, the cantata represents an extensive reworking of cantata BWV 59 of the same name, which Bach likely drafted in 1723 and then performed for the first time in 1724, albeit in a version that, by Bach’s standards, was somewhat provisional. In its revised form, the work’s theme of Pentecost – and thus the Holy Spirit who takes up “Wohnung” (abode) in humans, opens their hearts, grants them the ability to love and offers them comfort – is celebrated in an emotionally affecting and formally balanced symbiosis of word and music. Due to the distinct instrumentation of the arias and words of Jesus assigned to the bass soloist in the later composition, the cantata combines splendour and accessibility to great effect, while also demonstrating faithfulness to the Bible and a personal form of spiritual integration.

The opening movement, a full-chorus expansion of the duo from BWV 59, establishes a celebratory tone for the powerful Bible dictum from John 14:23. Through the fuller scoring of BWV 74 with a third trumpet, a partly obbligato oboe trio as well as alto and tenor voices, Bach creates a multi-chorus setting, but without compromising on sparkling clarity. In the following soprano aria “Komm, komm, mein Herze steht dir offen” (Come, come, my heart to thee is open), the faithful soul effusively reiterates the promise of Pentecost. While this aria also stems from BWV 59, the distinct change in scoring from violin and bass to oboe da caccia and soprano lends the setting a gentle ease. The alto recitative “Die Wohnung ist bereit” (Thy dwelling is prepared) confirms the yielding of the faithful heart, but links it to a Pentecostal interpretation of Jesus’ parting words that culminates in the entreaty “Drum laß mich nicht erleben, daß du gedenkst, von mir zu gehen” (So let me never suffer that thou shouldst mean from me to part).

Accompanied solely by the continuo, the bass aria presents an answer that likewise stems from Jesus’ words of farewell. While the promise it bestows allows for no doubt (“Ich gehe hin und komme wieder zu euch” – I go from here and come again unto you), the addition of the Bible phrase “Hättet ihr mich lieb, so würdet ihr euch freuen” (If I had your love, then would ye be rejoicing) introduces an admonitory tone. Bach, ever mindful of such constellations, thus combines a gently earnest vocal cantilena befitting Jesus’ words with a busy continuo motive, whose deftly modulating ascending lines reflect Jesus’ uphill battle to win the trust of the faithful and inspire them to emulate him.

Without a preceding recitative, the soloist in the tenor aria speaks for the faithful inspired by these proceedings and, in a gesture of musical self-encouragement, encourages them to play and sing with joy. Set in the bright key of G major and the lively style of a violin concerto, the extended movement transitions to a resounding declaration of faith, while also combining hope in the Second Coming of Christ with a warning against the temptations of Satan.

The following bass recitative alleviates all such concerns with a quote from Paul’s letter to the Romans: “Es ist nichts Verdammliches an denen, die in Christo Jesu sind” (There is nought destructible in any who in Christ, Lord Jesus, live). Here, the highly unusual accompaniment of three oboes breathes an expansive warmth and loving presence – mainly into the dogmatic statement – of this brief five-bar movement.

In a bravura-style setting uncommon in Bach’s oeuvre, the alto aria articulates the notion that only the suffering and death of Christ can save fallible humans and, by offering them a share of the heavenly legacy, give them strength to break free of their shackles – and even laugh at the brittle power of such bonds. Through the unusual combination of a highly dramatic vocal part and a dance-like orchestral setting reminiscent of the concerto-style overtures by Georg Philipp Telemann, Bach touches more than briefly on the style of operatic affect that was officially off limits to him in his capacity as cantor. Yet it is precisely the liberated violin solo, flying effortlessly across the chords, that proves to be the perfect evocation of the victorious Saviour.

Accompanied by the full orchestra, including a trumpet, the cantata closes with the second verse of Paul Gerhardt’s Pentecost chorale “Gott Vater sende deinen Geist” (God our Father send your spirit). Here, in good Lutheran fashion, the notion that the gifts of the Spirit are awarded not by merit of good deeds but by the grace of God is captured in the evocative word-painting of this powerfully simple cantional setting.

Libretto

Kerstin Wiese

J. S. Bach: “Whoever loves me will keep my word”, BWV 74, Cantata for Pentecost Sunday 1725

Exactly 300 years ago, a new chapter in music history was opened: Johann Sebastian Bach was elected Thomaskantor in Leipzig. For the first time in his career, he had the opportunity to compose church music for all Sundays and feast days of the year. He threw himself into the work with all his might. In the first two years, he presented his audience exclusively with his own works. While the pieces of the first year were very different in literary and musical terms, he set himself a clearly defined framework in the second year: for 40 weeks he composed exclusively choral cantatas based on a basic musical and poetic idea. But before Easter 1725, this year breaks off. After a few cantatas on texts of unknown origin, Bach concluded the year from Jubilate Sunday to Trinity Sunday with a sequence of nine cantatas on libretti by the Leipzig poet Christiane Mariane von Ziegler. Her texts inspired Bach to write highly expressive and varied compositions such as the magnificent Pentecost cantata we have just heard.

But who was this woman whose texts inspired Johann Sebastian Bach’s creativity to such a high degree? And what did Bach expect from the libretti on which he based his compositions?

Christiane Mariane was born in 1695 as the first of eight children into a respected family of lawyers in Leipzig. A series of strokes of fate befell her at a young age:

In her first decade of life, six of her siblings died. When she was nine years old, her father Franz Conrad Romanus – mayor of Leipzig at the time – was arrested for embezzlement. He remained in prison until his death – for a total of 41 years. 1711 – at the age of 16, Christiane Mariane married the nobleman Heinrich Levin von Könitz. But her husband died just one year later, shortly after the birth of her first daughter. At 19, she married Georg Christoph von Ziegler and had another daughter. She probably accompanied her husband, a military captain, on the campaigns in the Northern War. But around 1722 her second husband and both daughters also died. At just 27 years of age, Christiane Mariane von Ziegler was twice widowed and returned to her parental home in Leipzig.

For the next twenty years, she devoted herself entirely to literature and art. She published numerous poems, prose and translations. She vehemently defended women’s right to education and participation in literary and social discourse. She was one of the first women in Germany to run a literary-musical salon, thus creating a place where she could actively shape cultural and social life. In her salon, small societies of men and women met for stimulating conversations and erudite games. The guests dined, discussed literature, wrote impromptu poetry, played music and listened to concerts. Music played an important role in her salon. In the preliminary report of her first book of poems, she reports that virtuosos travelling through often treated her to “the honour of their encouragement”. Von Ziegler herself played the flute, lute, keyboard instruments and sang. In her collection of letters published in 1731, she pleaded for women to be allowed to play the transverse flute – an instrument commonly reserved for men in Germany. She corresponded with kapellmeisters and exchanged ideas about pieces of music with them. To what extent she discussed her cantata texts with Johann Sebastian Bach or whether he was a guest in her salon is unknown. Only once, in her poem “To a Garden Music” from 1729, does she mention Bach as a possible composer of a beautiful overture. It is also known that her aunt took on the sponsorship of Bach’s daughter Elisabeth Juliana Friederica.

In her publications, von Ziegler repeatedly emphasised women’s gift for natural speech, which predestined them for poetry, given equal educational opportunities. In the introduction to her poem “Vertheidigung unseres Geschlechts gegen die Mannspersonen” (Defending our Sex against Men), she wrote: “The natural way of writing is undoubtedly better than the artificial, pompous and turgid one. Women love the former and are, as it were, at home in it: but what exceeding things have not men’s characters sometimes given us to read? We readily admit that not all poets write in such an unnatural manner: but since no woman can yet be shown to have followed them in this, it remains a foregone conclusion that our sex is to be given the preference in this work.

This contribution is one of her earliest publications. It appeared in December 1725 – half a year after her collaboration with Bach – in the weekly journal “Die vernünftigen Tadlerinnen”. The editors around Johann Christoph Gottsched wanted to introduce a middle-class female readership to the ideas of the Enlightenment. Both the exclusively male editors and all the authors appeared under female pseudonyms.

Von Ziegler published her first volume of poetry under her own name in 1728 and thus penetrated deeply into the male sphere: The majority of the “Versuch in gebundener Schreib-Art” is devoted to secular themes, including many satirical, mocking and even crude poems. Among the few sacred poems, the revised versions of the cantata texts set to music by Bach stand out – poems, in other words, that were intended for performance in church and were actually performed there! Not only was the volume published under her own name. In the preface, she also emphasised that no man had edited the volume.

The incentive for the second part of the “Versuch”, published in 1729, on the other hand, were cantata texts – the focus is on 64 poems which, together with the nine already published, make up a complete volume. In the preface, von Ziegler gives advice on how composers could deal with the texts: Since they are quite long, the first part could be performed before the sermon, the second after. It would also be easy to make two volumes out of one.

In 1731, she was the first woman in Germany to publish a collection of letters: the “Moralische und vermischten Send-Schreiben”. The year before, she had been accepted as the only female member of the “German Society”, which was dedicated to the cultivation of the German language. Twice she received the prize for poetry, which the society awarded annually. In October 1733, at Gottsched’s suggestion, the University of Wittenberg made her the first woman in Germany to be awarded the title of poeta laureata – the highest honour as a poet. As a woman, however, she was not allowed to take part in the official coronation ceremony. The dean presented her with the certificate and the laurel branch in the presence of various dignitaries a week later in her flat.

The honour caused a stir in both positive and negative respects. On the one hand, she received many poems of homage; on the other, she was subjected to strong attacks. Caricatured playing cards with a blackened picture of Ziegler and anonymously published diatribes circulated. In them, Leipzig students claimed that she earned her living through commercial gambling and seduced young men. The trial against the authors of the vituperations was quashed on the orders of the Dresden court; universities were forbidden to award women in future without permission from Dresden. In the preface to her translation of Madeleine de Scudery’s “Scharfsinnige Unterredungen”, the self-confident poetess wrote in 1735: “The manifold impertinent vituperations have given me the advantage of not giving way one step to all malicious and base proceedings; in short, my enviers and enemies are not able to offend or upset me in the least.”

Her last major publication – the “Vermischten Schriften, in gebundener und ungebundener Rede” – appeared in 1739. Two years later she married the university professor Balthasar Adolf von Steinwehr and moved with him to Frankfurt an der Oder. She withdrew from public life for the most part.

But back to the question of what Bach expected from his librettists and his sole librettist.

Surprisingly little is known about Bach’s librettists and his collaboration with them. His only vintage based on a fixed principle – the chorale cantata vintage – remained unfinished. Unlike contemporaries such as Georg Philipp Telemann, Bach hardly ever resorted to printed cantata cycles. The majority of his librettists are therefore unknown to this day. Bach used a wide variety of texts for the Leipzig cantatas: older texts by Georg Christian Lehms, Salomo Franck or Erdmann Neumeister as well as libretti by young, literary and musically educated Leipzig poets such as Christian Friedrich Henrici, known as Picander, Christoph Birkmann or Christiane Mariane von Ziegler.

Bach was obviously interested in a wide range of stimuli and fresh ideas. The heterogeneous models offered him rich material to explore the possibilities of the cantata genre in many ways, to take up traditions and to create innovative solutions.

If he often had older texts adapted for his own purposes, it is obvious that he also sought artistic exchange with his local librettists. Considering that Bach had subjected himself to a tight corset for 40 weeks in his choral cantata year, it is not surprising that the varied Ziegler texts inspired him to the highest level of inventiveness. The many biblical words, for example, which Christiane Mariane von Ziegler used in very different places in her texts, gave Bach great freedom in his choice of movement types. In the cantata we heard today, Bach set three biblical passages to music in different ways: as a chorus in movement 1, as a bass aria in movement 4 and as a bass recitative in movement 6.

All in all, Bach experimented greatly in his Ziegler settings: in the cantata “Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein” BWV 128, for example, he emphasises the contrast between proclamation and silence by incorporating a recitative into the aria in the third movement. In the large-scale opening movement of the cantata “Ihr werdet weinen und heulen” BWV 103, he invents an impressive fugue solution to bring out the contrast between mourning and joy. In our cantata today, one of the things that stands out is the boldness and virtuosity of the altarpiece.

For Christiane Mariane von Ziegler, the nine cantata texts for Bach were her first public commission – and a singular one in her career: Bach’s settings enabled her to raise her voice in church – against the Lutheran verdict that women had to remain silent in church. That she had the self-confidence to accept such a commission at such an early stage in her career impresses me deeply. It was an absolute exception for a woman to provide libretti for church music. In view of this starting position, Bach’s decision for her texts was also a thoroughly bold undertaking. Did he consciously ignore the reservations of the clergy?

At the time of the settings, Christiane Mariane von Ziegler was still unknown as a poet. Her first publication, which also included the nine cantata texts, did not appear until three years later. Despite the difference in status and gender, she had a number of things in common with Johann Sebastian Bach: both moved in learned circles without having completed an academic education. Both were devout Lutherans. Both were self-confident artists who sought out diverse fields of activity and stood up for their convictions. An important composer, who is today one of the most famous personalities in German cultural history, set texts by an important poetess who has unjustly fallen into oblivion. Let us now listen to the Pentecost cantata “Whoever loves me will keep my word” a second time.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).