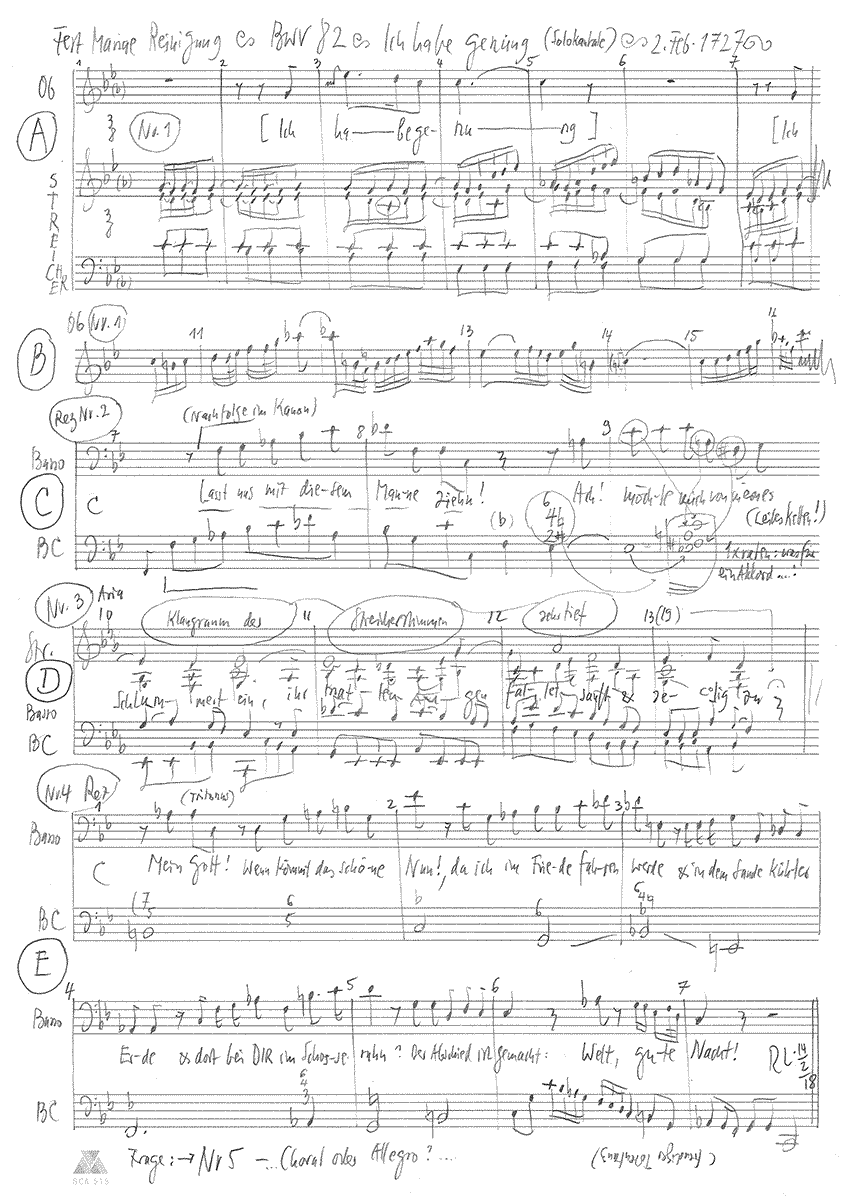

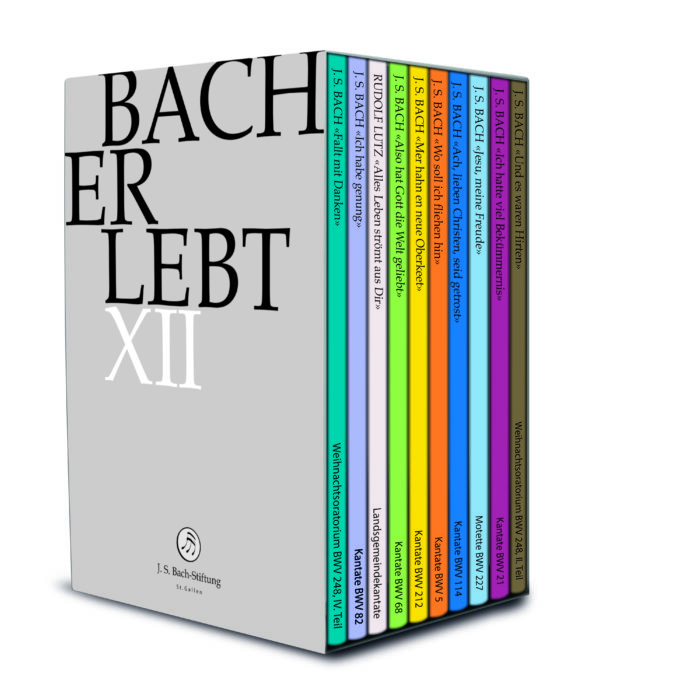

Ich habe genung

BWV 082 // For the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary

(I have now enough) for bass, oboe, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Soloists

Bass

Peter Harvey

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Olivia Schenkel

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Dana Karmon

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Karin Kaspers-Elekes

Recording & editing

Recording date

02/16/2018

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler, Nikolaus Matthes

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Christoph Birkmann (1703–1771)

First performance

The Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary

2 February 1727

Libretto

1. Arie

Ich habe genung,

ich habe den Heiland, das Hoffen der Frommen,

auf meine begierigen Arme genommen;

Ich habe genung!

Ich hab ihn erblickt,

mein Glaube hat Jesum ans Herze gedrückt,

nun wünsch ich noch heute mit Freuden

von hinnen zu scheiden:

Ich habe genung!

2. Rezitativ

Ich habe genung!

Mein Trost ist nur allein,

daß Jesus mein und ich sein eigen möchte sein.

Im Glauben halt ich ihn,

da seh ich auch mit Simeon

die Freude jenes Lebens schon.

Laßt uns mit diesem Manne ziehn!

Ach! möchte mich von meines Leibes Ketten

der Herr erretten;

ach! wäre doch mein Abschied hier,

mit Freuden sagt ich, Welt, zu dir:

Ich habe genung!

3. Arie

Schlummert ein, ihr matten Augen,

fallet sanft und selig zu!

Welt, ich bleibe nicht mehr hier,

hab ich doch kein Teil an dir,

das der Seele könnte taugen.

Schlummert ein, ihr matten Augen,

fallet sanft und selig zu!

Hier muß ich das Elend bauen,

aber dort, dort werd ich schauen

süßen Friede, stille Ruh.

4. Rezitativ

Mein Gott, wenn kömmt das schöne: Nun!,

da ich im Friede fahren werde

und in dem Sande kühler Erde

und dort bei dir im Schoße ruhn?

Der Abschied ist gemacht:

Welt, gute Nacht!

5. Arie

Ich freue mich auf meinen Tod,

ach! hätt er sich schon eingefunden!

Da entkomm ich aller Not,

die mich noch auf der Welt gebunden.

Karin Kaspers-Elekes

“Enough” is not the same as “finished”.

The individuality of the wish to die

It is an honour and a pleasure for me to be able to reflect with you this evening on the theological background

and content of the cantata composed by Johann Sebastian Bach for the Feast of the

The cantata was written by Johann Sebastian Bach for the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin Mary in 1727 and is entitled “Ich habe genung!

I have enough – I have enough! Questions arise on first hearing: enough of what? Is someone tired of what was and what is? What motivates this emotionally accentuating exclamation?

A magazine headlined a while back, “I’m old, tired, I’ve had enough!” Should we encounter this evening an examination of the moment of death and its occurrence, even possible or necessary influence on this moment?

It hardly seems possible to me to take in the work, interwoven of words and sounds, without rising memories of our own experienced farewells and dying wishes of perhaps close people, which have reached our ears and which we have tried to understand. But it also seems obvious to me not to leave out the current controversial discussions, the struggle over the question of so-called self-determined dying, which often comes across as if our highest right and expression of lived autonomy is to be able to determine our own time of death, and not to be able to live the life we have been given as self-determined as possible until the end.

“I have had enough!” What motivates this statement, which, as a motto that recurs four times, gave this cantata its title? Is it a retrospective view of life and a kind of capitulation, similar to the “I’ve had it!” of a temporarily luckless Italian football coach named Giovanni Trappatoni, who put a perplexed end to an epoch of his career with this somewhat bizarre-seeming sentence?

When the “I have had enough!” was first heard in Leipzig on 2 February 1727, the unity of the work was formed by Johann Sebastian Bach’s music and the words of a young student of theology and mathematics. Christoph Birkmann is just 24 years old and a private pupil of the Thomaskantor.

For a little more than two years now, thanks to a fledgling research project of the Bach Archive Leipzig and the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, we have been able to know that he gave his words to this and many other cantatas by Johann Sebastian Bach. The Nuremberg archive released the source of this knowledge to the Leipzig researcher Christine Blanken after history had long remained silent: it contained a volume of cantata poems published by Christoph Birkmann himself there, “Gott-geheiligte Sabbaths-Zehnden/bestehend aus Geistlichen Cantaten auf alle Hohe Fest-, Sonn- und Feyertage der Herspruckischen Kirchengemeinde zu Gottseeliger Erbauung gewiedmet von Christoph Bürkmann”.

Bach had already written works twice before for the feast day, the content of which is dedicated to the memory of the offering of Jesus in the temple of Jerusalem and which is still popularly called “Maria Lichtmess” (Candlemas) in our agendas. It is celebrated on 2 February according to our Gregorian calendar and had a fixed place in the liturgical calendar of the Christian churches in Leipzig in the 18th century. It was celebrated in a festive manner.

The feast day takes its theological content from the second chapter of the Gospel according to Luke. And as closely as the pericope there follows the narrative of the birth of Jesus Christ, so closely do we stand with this evening’s cantata, created for the day which, until the Second Vatican Council, rounded off the Christmas festival cycle in the Catholic Church, the day of Christ’s birth: 40 days have passed since the angel said, “Behold, I proclaim to you a great joy that will come to all the people. The Saviour is born to you today.”

40 days. Bethlehem. The visit of the shepherds and wise men. Hard times. The flight and the diversions via Egypt. On the 40th day they arrive. Mary. Joseph. And the child. They arrive at the temple in Jerusalem.

And there, for the first time, someone experiences what the young student, spoken of today as Christoph Birkmann, tries to put into these very words of his own in 1727: “I have had enough.”

It is Simeon, grown old, who takes the floor in the Holy of Holies of Judaism. His task: to wait. For the fulfilment of the promise. For the dawn of salvation. For the coming of the Messiah.

Simeon in Jerusalem has no news yet of what has happened in Bethlehem. For us, who are used to almost simultaneous communication over thousands of kilometres, this must be said. Many were waiting. The whole nation was waiting for the Messiah. But Simeon had had a very personal, spiritual experience that had assured him that he would not die before he saw the Messiah. When waiting becomes personal and reaches the heart, it becomes longing. And this yearning waiting gave meaning to his life.

And then it happens. A couple brings a boy about six weeks old into the temple.

So far, so good. That was nothing special yet. For according to Jewish rite, every first-born son had to be brought to the temple together with his mother and consecrated to God. He could be redeemed with a sum of money. In the case of this newborn, however, nothing is said about this. And a sacrifice had to be made so that the young mother could be considered pure again. Doves, symbol in Judaism for love and gentleness. And they were affordable, so that even young parents could afford it.

Up to this point, everything is actually as it always was. But when Simeon meets this child, the scene takes on another dimension. Simeon is deeply touched and realises: his longing waiting and with it the waiting of the whole people, it has reached its goal.

Simeon is so moved in the encounter that he begins to sing. It is the third hymn of praise that Luke delivers in his Gospel, his good news of God’s love for his people: Mary sings. Zacharias, the husband of Elizabeth, sings. And now Simeon too. Whenever it became solemn, people sang. At all transitions in life, people sang and continue to sing. Birth, baptism, wedding and abdication. Whenever what happens touches the innermost. It sounds as if from deep down in the soul: the touching truth of what has happened.

And now Simeon sings: “Lord, now you let your servant go in peace, as you have said; for my eyes have seen your Saviour, the salvation you have prepared before all peoples, a light for the enlightenment of the Gentiles and for the praise of your people Israel.”

How many years may Simeon have measured the quantity of time in his waiting and longing. Unfulfilled, longing time. But now, in the encounter, the moment of kairos occurs. Salvation time. Now it is not days, months or years that count. What counts now is the quality of time. This moment of encounter. It becomes significant. For Simeon. For the people of Israel. For world history. God’s salvation. And the life task of the old Simeon is fulfilled in recognising and blessing the child and his parents who accompany him. He lets them share in his wisdom, which is to become for them like a signpost and orientation for the unimaginable adversities they will encounter.

“Now, Lord, you let your servant go in peace.” He can trustingly place his life and his further journey in God’s hands. He does not speak about the time. There is no trace of haste. He expresses no weariness of life. But he does speak of the salvation that will happen to him, to the people and to the whole world. There is nothing in Luke’s account to suggest that he will die immediately. Just as the Lord said… There is talk of the relationship with God. Being embedded in the people of Israel and in the context of the world. And there is Hannah, the prophetess who has also grown old, whom Rembrandt, when he gives expression to the scene in his last painting before his death, paints at Simeon’s side, both blessing the child and praying. Simeon is a part of the greater whole, in relationships, he also lives for others, not just for himself. Simeon does not speak of himself and his perspective, not of his death, not of a future here or there. And never again will Luke say a word about how things went on with Simeon.

So much for the biblical-theological message.

On 2 February 1727, its actualisation resounds in the exclamation: “I have had enough!”

It is the interpretation of the young Christoph Birkmann, indeed it is even more: it is the personal appropriation of what the evangelist Luke, the theologian of salvation with the great interest in historical accuracy, tells of Simeon’s moment of salvation in the encounter with the Messiah.

“I have had enough!” The emotion of this moment becomes the starting point of Bach’s third work for the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord. It is no easy undertaking to put the moment of kairos, a moment of salvation, into words. Birkmann aims for the centre: “I have had enough!”

If the first lines of the verse are more concerned with reproducing Simeon’s experience of salvation, as Luke relates it, it is already the second part of the first aria that makes it possible to understand the experience of salvation, at least in a way that parallels it to the present and also updates it to the poet: “I have had enough, I have seen him! My faith has pressed Jesus to my heart!”

In the recitative that follows, the poet takes this path a step further, again coming from the most inner Karios experience: “I have had enough!”

His scopus: the experience of Christ’s communion is also accessible to man living more than 1720 years later. This is one of the central theological statements of the cantata text: “My only comfort is that Jesus wants to be mine and I his own.” It is as if we are hearing the answer to the fundamental first question in the Heidelberg Catechism (1563) written by Zacharias Ursinus in 1563: “What is your only consolation in life and in death? That in life and in death, body and soul, I belong not to myself but to my Lord Jesus Christ.”

Inwardness arises in faith. Intimacy. And so the poet describes a kind of inner imitation of Simeon for his own assurance of faith: a mystical communion with Christ is also possible in faith for the presently living and can become just as meaningful for the individual.

In the phase of late or reform orthodoxy and at the beginning of modernity, talk of God and faith in him is challenged from two sides: by Pietism on the one hand and the beginning of the Enlightenment on the other. And both sides discover the I.

In essence, this means that the I of Pietism is concerned with one’s own salvation before God and in God. The I of the Enlightenment is concerned with emancipating oneself, more or less in relation to God.

It is 40 years until the “Sturm und Drang”, and it seems as if melancholy, which the literary scholar Annette Wallbruch calls “the fashionable disease of the 18th century”, already reveals in the words of the young Christoph Birkmann those emotions and foreshadows the otherworldliness that in 1774 give Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s suffering young Werther his features and bring his life’s fate to its tragic conclusion.

On the one hand, we encounter a process of individualisation that applies both to the experience of oneness with Christ and to the afterlife of one’s own future. Luke, the theologian of salvation, also attaches importance to the former in the tradition, but very much with reference to the significance of the moment of salvation for the history of salvation of Israel and the whole world. The consequence of the rejection of the world and the turning towards the existence beyond is increasingly due to the development of the history of theology, which attempts to answer the question of personal salvation.

When, at the same time, this recitative sounds the plea: “Ah! May the Lord save me from the chains of my body! “we are reminded of the many ways in which the urban population, even in a progressive agglomeration such as Leipzig, could fall ill with epidemics at this time, as well as of a theological appreciation of the immaterial component of human existence. “Chains” are not only in 18th century poetry and philosophy an expression of bondage, of being trapped in the less valued material, which is to be followed by the transition into spiritual, true existence.

The text of the following aria is also indebted to a dialectical view of the world and of man, on the one hand attached to matter and on the other reaching out to the spiritual, true life beyond: Man is unfree, he is nolens volens an active part of worldly misery: “Here I must build misery.” We stand with him before Luther’s “homo incurvatus in se”, man bent in himself. There is no escape. We are sinners. That is true. Only in the relationship with Christ is there salvation for the believer.

But the longing for peace and salvation is ultimately satisfied only after death. While the Lucan tradition names the moment of salvation as the cause of the inner finding of peace, which allows the continuation to fade into the background, Christoph Birkmann’s words focus on the sphere of post-death existence as a space of longing and future experience of peace and tranquillity.

Those who inwardly take Christ to their own heart and thus spiritually-emotionally comprehend Simeon’s recognition of themselves have taken their leave: “Goodbye is done, world, good night!

The consequence of the salvific communion with Christ flows into a perspective of the future described with longing and feeling:

“I look forward to my death, oh, if it had already come. Then I will escape all the misery that still binds me in the world!

It must be remembered that the young lyricist, who knew Simeon’s “Nunc dimittis”, which was also part of the Lutheran Church’s daily night prayer and in some places also part of the liturgy of the Lord’s Supper, thus also knew it from active liturgical use, feels the moment of salvation of Christ’s communion in an intimate, uplifting adaptation in such a way that worldly existence is completely disregarded in comparison with the longed-for spiritual existence. “I’ve had enough!” A current dying wish? An emotional snapshot? A theological-artistic means of expressing the healing communion with Christ in faith and its existential significance of finding sufficiency? Most likely the latter. It is important to remember: the creator of the cantata text himself served as a pastor in Nuremberg for many a decade until his death.

We can listen to Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantata “I have had enough!” this evening as a theological interpretation according to the interpretation of the time – and put it aside again. But we can also be inspired and sensitised – also for dealing with today’s dying wishes, the theoretically thought-out ones and the ones concretely motivated by serious personal experiences.

Not every expressed “I’ve had enough!”, not every expressed wish to die is ultimately aimed at ending one’s own life or even accelerating it.

Every question about the time of “now”, every longing for death, every “I’ve had enough” has an individual face and, when expressed, seeks resonance with the one to whom it is entrusted. I return to the beginning and ask: what motivates a concrete “I have enough”?

We not infrequently talk about the dignity of the human being in itself. It is inviolable. In the concrete situation, I think this means that it is due to this value, which is bestowed on every human being qua his or her humanity and cannot or does not have to be earned, that his or her “I’ve had enough!” is not heard hastily as “I’m done”.

Dying wishes are eloquent. Those who express them, according to my experience from many accompaniments of seriously ill people, express much more often that life as it is at the moment lacks quality of life. Where they are expressed, they seek YOU. They seek encounter and express loneliness, longings and inner development processes – and are not infrequently an expression of the longing for a healing experience in the mourning of a life that is challenging under such changed conditions after the diagnosis of a serious illness. “I’ve been playing in a different league since my diagnosis.” Or: “Everything I start now, I somehow see through a veil. Does it all still make sense? And for whom?”

Does someone open up the space for me and give me some of their time to think about where there can be hopes that are sustainable, where the hope for health will no longer be fulfilled according to human judgement? Dying wishes are individual and seek the resonance of a listening, empathetic counterpart with time for the melody of life that is hidden in and behind them. Healing moments of encounter need relationship. It is to be hoped and prayed for that moments of salvation, in which sufficiency is experienced, can also be experienced when the experience of lack recedes and peace is allowed to set in with the less than perfect life. I borrow words from Hilde Domin that describe this attitude:

“Don’t get tired, but hold out your hand to the miracle like a bird! “Perhaps there is more than we see. Sense. Foresee. Another, more deeply touching miracle. One that makes whole. Fulfilled time. A healing moment. A hopeful exhale. And one that can then say, when the time comes, “I have had enough!”

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).