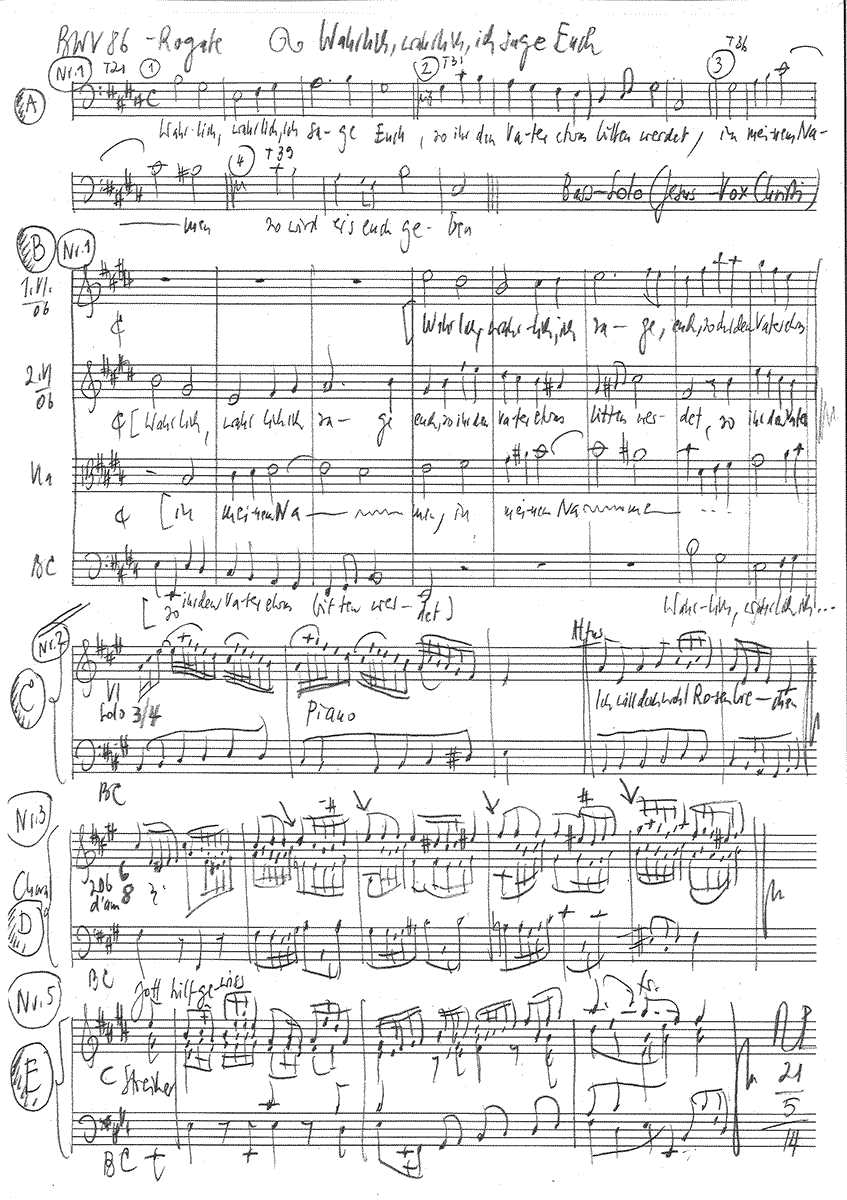

Wahrlich, wahrlich, ich sage euch

BWV 086 // For Rogate

(Truly, truly, I say to you) for soprano (vocal ensemble), alto, tenor and bass, oboe d’ amore I+II, bassoon, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Susanne Seitter, Alexa Vogel

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Eva Borhi, Christoph Rudolf

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Krone

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Kerstin Kramp, Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Rudolf Wachter

Recording & editing

Recording date

05/23/2014

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

John 16:23

Text No. 3

Georg Grünwald (1530)

Text No. 6

Paul Speratus (1523)

Text No. 2, 4, 5

Poet unknown

First performance

Rogate,

14 May 1724, Leipzig

In-depth analysis

Cantata BWV 86, composed for the Fifth Sunday after Easter, was first performed on 14 May 1724. Today, determining the instrumentation of the individual movements requires some guesswork, as the extant original score contains no instructions and the performance parts have unfortunately been lost. The libretto opens with a passage from John 16:23 that Bach skilfully sets to music, evoking not only the comforting words of Jesus to his disciples but also his latent irritation that they had yet to fully understand him as the path to the Father. In this opening movement, the sonorous lines of the bass vocalist are woven into a freely contrapuntal string setting that is lent a tone of silken warmth by the addition of oboes d’amore.

The following aria is characterised by an exceptional light-footedness, almost as if the causal relationship between the benevolent Son of God and hopeful human beings needed further emphasis. Despite the sparse scoring for alto, violin and continuo, the setting delights from the outset through its combination of cheerful continuo quavers, adroit text interpretation and exuberant, virtuosic violin writing. Indeed, here the music is less about the (literally) flowery metaphors in the text than the release of physical energy, which, perhaps, realises precisely what the introductory words of the Saviour demand: the easy joy and active trust necessary to master the difficulties of life – not to mention this challenging violin part.

After the Bible saying and its free versification, the chorale then introduces the third text source and, with it, a dimension of the church community. Nonetheless, Bach evidently wished to retain the musical impetus of the preceding movement, and thus set the hymn verse “Und was der ewig gütig Gott” (And what the ever gracious God) not for a four-part choir but for a soprano accompanied by two oboes. Thanks to the lilting 6/8-metre and the light, energetic motifs of the instrumental voices, this setting radiates a vitality and confidence similar to the preceding aria, its muted F-sharp minor tonality notwithstanding.

Then follows the cantata’s first recitative. Despite its short length, this section shapes the cantata’s narrative arc by succinctly describing the difference between God’s promises and the imperfection of the world. Through the distinct emphasis on the words “verspricht” (pledges) and “hält” (keeps), Bach’s tenor part subtly holds up a mirror to many a listener.

This didactic passage, however, proves to be a mere intermezzo in a lively series of movements that, largely due to the spontaneity of the instrumental parts, increasingly takes on traits of a Cecilian celebration of music. Accordingly, in the following tenor aria, Bach creates a dance-like setting whose foot-stamping motif is transformed into the recurring vocal motto “Gott hilft gewiß” (God’s help is sure), which then inspires the vivacious figurations of the first violin part through its organic development. In terms of motivic concision and evocative presence, Bach could theoretically have had this catchy and unfortunately all too short piece performed on the stage of the Leipzig opera (unfortunately shuttered in 1720).

Following this cheery musical “morning pint”, all that remains is for the confident hymn by Paulus Speratus (1530) to formally close this equally charming and concise cantata in a powerful chorale. While the compact movements and sparse scoring of this work suggest that the energies of the musicians, especially the vocalists, were to be conserved prior to Ascension and Pentecost, in this cantata, Bach nonetheless skilfully realises a figural piece characterised by unaffected joy in musicmaking and concentrated application of form.

Libretto

1. Arioso (Bass)

»Wahrlich, wahrlich, ich sage euch, so ihr den Vater etwas

bitten werdet in meinem Namen, so wird ers euch geben.«

2. Arie (Alt)

Ich will doch wohl Rosen brechen,

wenn mich gleich die Dornen stechen.

Denn ich bin der Zuversicht,

daß mein Bitten und mein Flehen Gott gewiß zu Herzen gehen,

weil es mir sein Wort verspricht.

3. Choral

Und was der ewig gütig Gott

in seinem Wort versprochen hat,

geschworn bei seinem Namen,

das hält und gibt er gwiß fürwahr.

Der helf uns zu der Engel Schar

durch Jesum Christum! amen!

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Gott macht es nicht gleich wie die Welt,

die viel verspricht und wenig hält;

denn was er zusagt, muß geschehen,

daß man daran kann seine Lust und Freude sehen.

5. Arie (Tenor)

Gott hilft gewiß,

wird gleich die Hülfe aufgeschoben,

wird sie doch drum nicht aufgehoben.

Denn Gottes Wort bezeiget dies:

Gott hilft gewiß!

6. Choral

Die Hoffnung wart’ der rechten Zeit,

was Gottes Wort zusaget;

wenn das geschehen soll zur Freud,

setzt Gott kein gwisse Tage.

Er weiß wohl, wenns am besten ist,

und braucht an uns kein arge List;

des solln wir ihm vertrauen.

Rudolf Wachter

Language and Religion

People’s fear of the future

Language is the most powerful and wondrous tool that we humans have acquired in the course of evolution. In the cantata BWV 86 “Verily, verily, I say unto you” it plays a central role in the word “promise”. This is no accident. Language and religion have always been closely intertwined. The following reflection, which requires a journey into the past, is about this.

What is the essence, what is the origin of religion? This question has long occupied theology, religious studies, anthropology, ethnology and other sciences. There is agreement that the burial of the dead by humans of the species Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis since about 100,000 years ago and the grave goods that have been reliably proven since about 30,000 years ago presuppose some kind of religion. The grave goods in particular suggest that these people were concerned about what would happen to their relatives, and thus to themselves, after death. But this is one of the core issues of every religion. Death is one of the most fascinating mysteries and at the same time the central nuisance of our existence. Today we spend enormous sums of money to delay it, and for thousands of years the greatest thinkers have been intensively occupied with conquering the fear of it, almost as intensively as with establishing the essence of love and sexuality, the counterpoint of death.

But the decisive prerequisite for our ability to think into the future and to form ideas about an afterlife is language. And as far as language is concerned, science is unanimously of the opinion that it had already reached its present stage of development when our species was formed 200,000 years ago, and that our ability to think and our imagination would not exist without it. Today, it is also assumed that Neanderthals were also capable of a spoken language in view of their quasi-religious actions and the complex way of life based on the division of labour that they already knew. Anatomical and, more recently, genetic reasons also speak in favour of this. Thus, language must have already developed in the common ancestors of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

It will probably never be possible to say anything reliable about what the language of our closest relatives was like. But we can assume that already 100,000 or 150,000 years ago, when we all lived in Africa (and were undoubtedly all dark-skinned), we asked each other questions, gave explanations, told each other stories, made requests, gave advice and orders or objected to them, that we flirted with each other and exchanged verbal endearments or nagged and argued, praised, rebuked, comforted or insulted each other, just as we do today. And – that we always looked anxiously into the future, talked to each other about the manifold threats and developed strategies to ward them off.

Let’s try to put ourselves in those people’s shoes for a moment! In some ways, their uncertainty about the future was not very different from ours. They could talk to each other, make pacts, promise each other peace and support and, if necessary, confirm this in front of witnesses and by oath. They also interacted with animals and plants, which still have something unpredictable and mysterious about them, in a similar way as we do.

However, their relationship to sudden natural disasters such as storms, lightning, floods, rockfalls, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, but also continuous rain or drought, to which they were largely helplessly exposed, was completely different. Although we still often have to contend with these evils, we have acquired considerable advantages over the past – even if these are still very unevenly distributed across the world’s regions: We understand the larger geological and meteorological relationships and can now predict the weather quite reliably for an entire week; thanks to centuries of experience, most of it documented in writing, and an engineering system that goes back to antiquity, we have taken various structural measures to tame the destructive effects of the forces of nature; we also have professional rescue services, highly developed medical care and insurance to cushion financial losses. Such knowledge and precautions did not exist until a few centuries ago.

And let us imagine: With what feeling would we go to sleep in the evening if we did not know for sure that the sun would rise again tomorrow? For us, this is so self-evident that we don’t even think about this question any more. As we know, the Earth has been revolving around the Sun for 4.6 billion years, and according to the latest findings, it will continue to do so for another 7 billion years, even if it will become rather uncomfortable here in just under a billion years. For our distant ancestors, on the other hand, it was at best a reasonable hope that a new morning would dawn after the night. This was not least due to the fact that the history that had been handed down was so short. In cultures without writing, memory goes back no more than four generations, by which time one has already arrived at the time of the mythical primordial ancestor, and the sun, moon and stars, as well as life on earth, cannot in turn be much older. In the creation account that entered the beginning of the Bible, seven days sufficed until Adam. It is obvious: people with a level of knowledge in which the history of the universe covers about 150 years cannot be as confident that the sun will rise again tomorrow as we are!

In fact, for most of human history, the earth, the heavenly bodies, the seasons, fire, water, wind and weather were not understood in the same sense as they are today. Rather, these powers that could so actively intervene in life were ascribed a will and thus the status of living beings, only that they were even more mysterious than animals and plants. – And it was to fathom the will of all these powers and to keep them as placated as possible that all the zeal of the people of those cultures was directed. Spirits, goblins, nymphs, monsters and lesser deities, friendly or hostile, dwelt in every cave, in every bush and tree, in every river and lake. Great and powerful gods, on the other hand, dwelt on Mount Olympus, in Valhalla or in other divine heavens, some also in the sea and in the underworld. Priests and priestesses were chosen to constantly investigate the state of their deity and, in the event of an upset, to provide successful recipes for their reconciliation. The interpretation of omens, oracles, atonement and purification rituals, prayers and sacrificial acts had a correspondingly high status.

All this lively interaction with the numinous in the world served people above all to gain more certainty about the course of the future and to influence it as much as possible in their favour, often with the help of the gods, whom they strove to make merciful. Of course, all of this was almost always done through language. One spoke with the nymph in the tree, the river god, the dwarf in the cave. People muttered spells, addressed prayers to the gods and sang hymns of praise to them. A wonderful collection of hymns is the Indian Rigveda, which was written about 3000 years ago. Quite a few of the more than 1000 songs were composed precisely to welcome and praise the sun and recited at its rising, not least to convince it to come back the next day. The magical poems and sayings of the slightly younger Atharvaveda guarantee long life, happiness in house and home, they free from sin, help in war, in the game of dice, in love, in childlessness, against all kinds of illnesses, bewitchment, against a rival or against a superior negotiating partner. Or let us recall the beginning of Homer’s Iliad, where it is described how the plague decimated the Greek army encamped before Troia in a terrible way and the seer Kalchas finally diagnosed that Apollo was angry and had to be reconciled. And as late as 54 BC, when the city of Rome was hit by a terrible flood, the people saw in it the wrath of the gods and rebelled against the authorities; the reason was that a shady politician, Aulus Gabinius, had been acquitted of the charge of having violated divine regulations thanks to a few powerful friends.

We find such dealings with the numinous around the globe in countless cultures and religions – with one striking exception: the God of Israel. As a monopolist, this God was not exposed to any competition. In polytheistic religions, it is quite common to play one deity off against the other; if one does not help, one simply turns to another. In the case of the God of the Old Testament, this was ruled out from the outset, and any attempt to change his mind by offering sacrifices proved useless. Only unconditional trust in him led to the goal. The sacrificial death of Christ was indeed a sacrifice of atonement, but it was God Himself who performed it, who sacrificed Himself, as it were. So for us Christians, too, the only way to come to terms with this God is to believe in the efficacy of that sacrifice, whereby we cannot help but praise him as a good God and trust in his willingness to show mercy and help.

It is precisely of this trusting attitude of man towards this extraordinary God that our cantata tells, of a promise that God has made to us, and that there is no doubt that he will keep it. What exactly is promised is not said, but what is ultimately meant – from an anthropological point of view – is redemption from those very fears of the future that have been driving us humans, and indeed each and every one of us, ever since we were able to speak and understood that time is running and that we are mortal. The only uncertainty concerns the time of fulfilment of the promise. But even for that, as we know, Christianity has a well-thought-out answer ready: Even if we should not live to see the return of the Son of Man, God will keep his promise, and the best preparation, almost even the provisional redemption, is our individual death. Many a Bach cantata text dealing with the longing for death has already impressed this upon us. With this highly successful formula, Christianity has been taking the sting out of death for two thousand years, especially the inherent characteristic that we do not know when and how it will befall each and every one of us: mors certa, hora incerta.

So now we return from our journey through time and ask ourselves: What is our situation today compared to that of our ancestors in Bach’s time or in antiquity or 100,000 years ago? The horizon of our view of the world has expanded greatly thanks to the natural sciences. I personally would not want to miss this progress. Nevertheless, no one will want to claim that we really understand the world as a result. And as far as the basic conditions of our human existence are concerned, especially the fear of the future and of death, things have at least improved in two respects: Firstly – quite prosaically, but very importantly – painkillers and other palliatives are now available to make suffering more bearable. Secondly, thanks to libraries and the internet, the best texts of mankind dealing with the problems of our existence are now more easily accessible than ever. Whether we take the trouble to deal with them in the necessary depth is another question.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).