Ich hab in Gottes Herz und Sinn

BWV 092 // For Septuagesimae

(I have to Godís own heart and mind) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe díamore I+II, strings and bassos continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

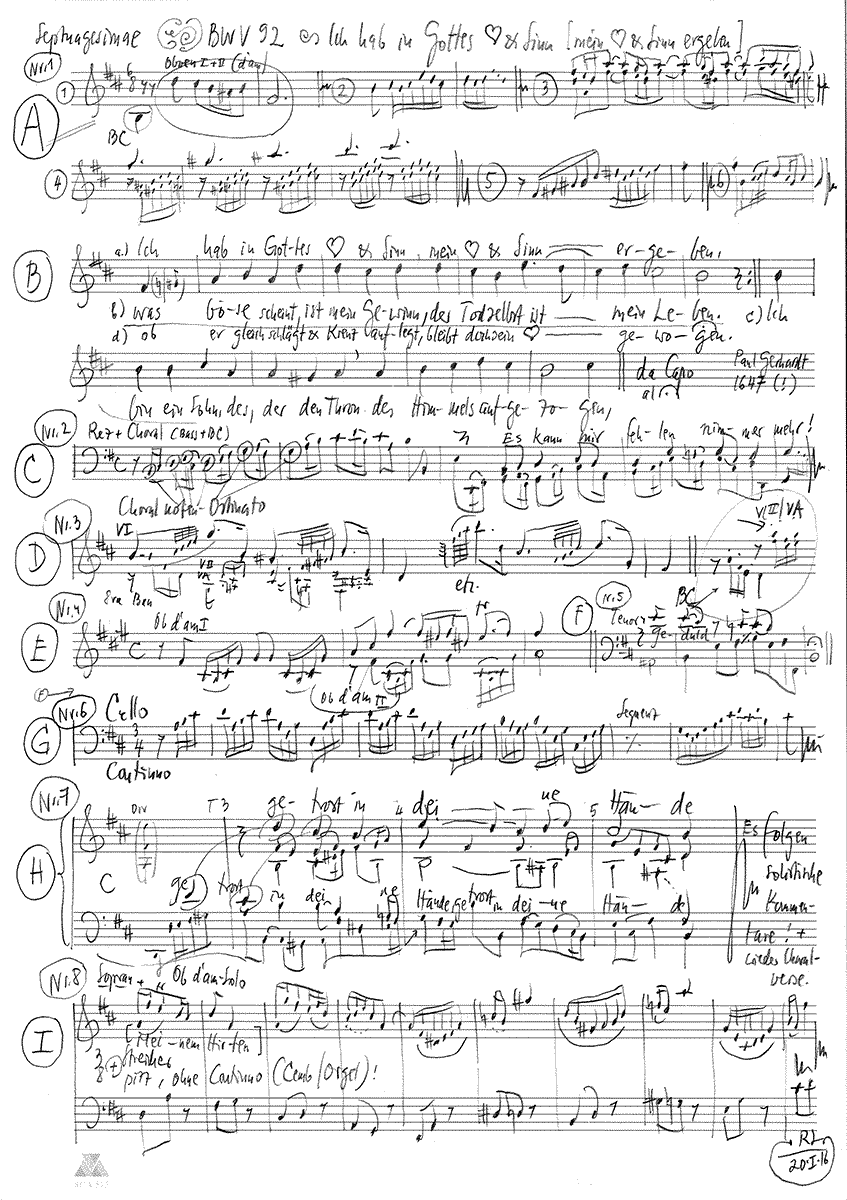

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Olivia Fündeling, Damaris Rickhaus, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran Rediger

Alto

Antonia Frey, Liliana Lafranchi, Misa Lamdark, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Sören Richter, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Daniel Pérez, Oliver Rudin, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Dorothee Mühleisen, Christoph Rudolf, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Sarah Krone, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe d’amore

Katharina Arfken, Dominik Melicharek

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Andreas Köhler

Recording & editing

Recording date

22.01.2016

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Poet unknown

Text No. 1, 4, 9

Paul Gerhardt, 1647

First performance

Septuagesima Sunday,

28 January 1725

In-depth analysis

Composed for 28 February 1725, Cantata BWV 92 forms part of Bach’s chorale cantata cycle. Even by the standards of this largescale project, the cantata’s underlying chorale by Paul Gerhardt features particularly frequently and in various different forms throughout the libretto.

The introductory chorus is set in the key of B minor. Although the head motif is broody and contemplative, the oboes d’amore radiate a confident tone, engaging in a charming concertante exchange with the tutti ensemble. The ensuing musical dialogue between the orchestra and the choir, with the cantus firmus in the soprano voice, exudes a gentle tenor of rueful concession – Christians must learn to bear their share of the Saviour’s inheritance and are obliged to repeatedly renew their debt.

In the following recitative, the hymn melody is present from the outset in the continuo part; indeed, Bach specifically designates the melody as an intensely expressive musical layer (“chorale”). In this setting, the interplay of the chorale with the recitative text demonstrates with rare clarity that the recitatives of the chorale cantata cycles are in principle paraphrases of the Protestant hymns that, for their part, transformed the gospels into singable verse. The import of the text, illustrated by references to biblical figures such as Jonah and Peter, culminates in the home message that it is God’s will to save and give strength to those of true faith.

After this dense outline of the theological issue at hand, the desired explanation emerges in the tenor aria “Seht, seht, wie reißt, wie bricht, wie fällt, was Gottes starker Arm nicht hält” (Mark, mark! it snaps, it breaks, it falls, What God’s own mighty arm holds not). A veritable ocean storm at sea ensues: with a broken-chord ostinato figure underscoring a chain of short, buffeted phrases and gusting storm winds, the music spells out what lies in store for those out of favour with God. In the middle section, the long pedal notes represent the congregation that has gained strength from God’s power, ere the true enemy – Satan and his “Wüten, Rasen, Krachen” (fury, raving, raging) – is revealed and ultimately overcome. Through Bach’s consummate skill, this combative setting is rendered as a work of triumphant fortitude; an abbreviated da capo concludes this unexpectedly heroic movement.

In the next setting, the chorale forms the structure of the movement. Written in the style of an organ arrangement, the cantus firmus (alto voice) is embedded in a captivating trio of two oboes d’amore and continuo; the ornate elegance of the accompanying voices accentuates by way of contrast the clarity and pious simplicity of the chorale melody.

This inspires an energetic recitative in which the tenor resolves to reject anxiety and insecurity and instead embrace the trials of human existence. In this setting, the sighing figures of the closing phrase illustrate how Jesus’ humility in the face of his crucifixion can serve as a model for abandoning fear and prevailing under duress.

Accompanied solely by the continuo, the bass aria “Brausen von den rauhen Winden” (The raging of the winds so cruel) sustains this argument with vivid imagery, returning to the metaphors of the storm and force of nature to present a pacey and complex interpretation of the human path to salvation: good comes to bear only through struggle and resistance; indeed, it is the test of the cross that yields fruit in the Christian, and without these trials, there can be no joyous harvest or spiritual fulfilment. In this perpetuum mobile setting on existential concerns, the listener is implored to submit to the wisdom of God and to welcome the discipline of Christ’s teachings (“Kü.t seines Sohnes Hand, verehrt die treue Zucht” – Kiss ye his own Son’s hand, revere his faithful care).

The chorale then returns in the form of a four-part recitative set as a type of litany with interpolated verses. Upon hearing the opening chordal phrase, listeners could easily mistake the setting for the closing chorale, but because Bach breaks up the second line of each chorale quote with a florid figure originating in the bass part, it becomes clear that the setting is an additional artistic variation. The newly texted interpolations speak of the Saviour’s “Brudersinn” (brotherhood) and present a series of images of trust and beatitude. In doing so, a “neues Lied” (new refrain) is prepared for Jesus, the Prince of Peace; in the following aria, this song emerges as a tender soprano cantilena over pizzicato strings. In this direct encounter of the faithful soul and the Saviour, all worldly experience is forgotten to make way for a tender moment of mutual commitment, ere the delicate polonaise on trust in God culminates in a death-defying apotheosis of faith: “Amen, Vater nimm mich an!” (Amen, Father take me now!).

The closing chorale brings a return to the opening key of B minor and, by travelling over many a “Bahn und Steg” (road and path), is replete with moving imagery of life’s journey. After the various experiments on form and the chorale in the preceding movements, the simply declaimed prayer of this masterly unpretentious movement is most especially poignant.

Libretto

1. Chor

Ich hab in Gottes Herz und Sinn

mein Herz und Sinn ergeben,

was böse scheint, ist mein Gewinn,

der Tod selbst ist mein Leben.

Ich bin ein Sohn

des, der den Thron

des Himmels aufgezogen;

ob er gleich schlägt

und Kreuz auflegt,

bleibt doch sein Herz gewogen.

2. Choral und Rezitativ (Bass)

Es kann mir fehlen nimmermehr!

Es müssen eh’r,

wie selbst der treue Zeuge spricht,

mit Prasseln und mit grausem Knallen

die Berge und die Hügel fallen:

mein Heiland aber trüget nicht,

mein Vater muß mich lieben.

Durch Jesu rotes Blut bin ich in seine Hand geschrieben;

er schützt mich doch!

Wenn er mich auch gleich wirft ins Meer,

so lebt der Herr auf großen Wassern noch,

der hat mir selbst mein Leben zugeteilt,

drum werden sie mich nicht ersäufen.

Wenn mich die Wellen schon ergreifen

und ihre Wut mit mir zum Abgrund eilt,

so will er mich nur üben,

ob ich an Jonam werde denken,

ob ich den Sinn mit Petro auf ihn werde lenken.

Er will mich stark im Glauben machen,

er will vor meine Seele wachen

er will für

und mein Gemüt,

das immer wankt und weicht,

in seiner Güt,

der an Beständigkeit nichts gleicht,

gewöhnen fest zu stehen.

Mein Fuß soll fest

bis an der Tage letzten Rest

sich hier auf diesen Felsen gründen.

Halt ich denn Stand,

und lasse mich in felsenfestem Glauben finden,

weiß seine Hand,

die er mir schon vom Himmel beut,

zu rechter Zeit

mich wieder zu erhöhen.

3. Arie (Tenor)

Seht, seht! wie reißt, wie bricht, wie fällt,

was Gottes starker Arm nicht hält.

Seht aber fest und unbeweglich prangen,

was unser Held mit seiner Macht umfangen.

Laßt Satan wüten, rasen, krachen,

der starke Gott wird uns unüberwindlich machen.

4. Choral (Alt)

Zudem ist Weisheit und Verstand bei ihm ohn alle Maßen,

Zeit, Ort und Stund ist ihm bekannt, zu tun und auch zu lassen.

Er weiß, wenn Freud,

er weiß, wenn Leid

uns, seinen Kindern, diene,

und was er tut,

ist alles gut,

ob’s noch so traurig schiene.

5. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Wir wollen nun nicht länger zagen

und uns mit Fleisch und Blut,

weil wir in Gottes Hut,

so furchtsam wie bisher befragen.

Ich denke dran,

wie Jesus nicht gefürcht’ das tausendfache Leiden;

er sah es an

als eine Quelle ewger Freuden.

Und dir, mein Christ,

wird deine Angst und Qual, dein bitter Kreuz und Pein

um Jesu willen Heil und Zucker sein.

Vertraue Gottes Huld

und merke noch, was nötig ist:

Geduld! Geduld!

6. Arie (Bass)

Das Stürmen von den rauhen Winden

Das Brausen

macht, daß wir volle Ähren finden.

Des Kreuzes Ungestüm schafft bei den Christen Frucht,

drum laßt uns alle unser Leben

dem weisen Herrscher ganz ergeben.

Küßt seines Sohnes Hand, verehrt die treue Zucht.

7. Choral und Rezitativ (Sopran, Alt, Tenor, Bass)

Ei nun, mein Gott, so fall ich dir

getrost in deine Hände.

Bass

So spricht der Gott gelass’ne Geist,

wenn er des Heilands Brudersinn

und Gottes Treue gläubig preist.

Nimm mich, und mache es mit mir

bis an mein letztes Ende.

Tenor

Ich weiß gewiß,

daß ich ohnfehlbar selig bin,

wenn meine Not und mein Bekümmernis

von dir so wird geendigt werden:

Wie du wohl weißt,

daß meinem Geist

dadurch sein Nutz entstehe,

Alt

daß schon auf dieser Erden,

dem Satan zum Verdruß,

dein Himmelreich sich in mir zeigen muß

und deine Ehr

je mehr und mehr

sich in ihr selbst erhöhe.

Sopran

So kann mein Herz nach deinem Willen

sich, o mein Jesu, selig stillen,

und ich kann bei gedämpften Saiten

dem Friedensfürst ein neues Lied bereiten.

8. Arie (Sopran)

Meinem Hirten bleib ich treu.

Will er mir den Kreuzkelch füllen,

ruh ich ganz in seinem Willen,

er steht mir im Leiden bei.

Es wird dennoch nach dem Weinen,

Jesu Sonne wieder scheinen.

Meinem Hirten bleib ich treu.

Jesu leb ich, der wird walten,

freu dich, Herz, du sollst erkalten,

Jesus hat genug getan.

Amen: Vater, nimm mich an!

9. Choral

Soll ich denn auch des Todes Weg

und finstre Straße reisen,

wohlan! ich tret auf Bahn und Steg,

den mir dein’ Augen weisen.

Du bist mein Hirt,

der alles wird

zu solchem Ende kehren,

daß ich einmal

in deinem Saal

dich ewig möge ehren.

Andreas Köhler

“And what He does is all good”

The cantata “Ich hab in Gottes Herz und Sinn” (BWV 92) invites us to reflect on an old question: How does evil come into the world?

Thanksgiving, praise and petition

“He knows when joy,

he knows when sorrow

serve us, his children,

and what he does,

All is well,

“no matter how sad it may seem.”

So we have just heard, wonderfully sung and played, the verses of the Lutheran clergyman Paul Gerhardt, written four centuries ago. Familiar words. To them belongs a story that we want to recall – at least in leaps and bounds. Since time immemorial, man has praised and extolled God’s works and asked for mercy, for protection from harm. Thus the psalmist sings

“Hallelujah! Give thanks to the Lord, for he is kind:

Everlasting is his goodness.”

Man rejoices in the abundance offered him in the world: awakening of nature in spring, summer warmth and autumn harvest, juice of the vines and happiness in the hunt; he is equally fearful of the dangers that lurk: Hail and frost, threatening enemies, disease and death. For since he has taken into account all the mighty forces to which he is exposed, since he has become aware of them, yes, since he has developed and sharpened his mind on them, he considers them in turn as spiritual, even divine rulers whom he has to ask, who are to be praised, who are to be thanked: “My King and my God!” cries the psalmist. After all, he expects his salvation through him – and the averting of destruction. What else could he do in the face of such violence?

Arbitrary power of spirits and gods, benevolent and cruel? So it seems. It seemed that way for a long time. But finally a thinker opposed this: Plato. His Socrates asks rhetorically in the round of friends: “But surely God is good in reality and must be portrayed as such?”

How does evil come into the world?

But if the divine is exclusively good, how does evil come into the world? Plato’s answer: The divine is innocent of this. Poets should be forbidden to attribute evil to the gods. Bad people are guilty of evil, and when God punishes them, he does nothing evil, but is merely just. Since then, God is no longer arbitrary, but only good and just. Evil lies solely in man’s deeds.

However, in the consciousness of individuals it continued to mull: Why then was man – by God! – created so badly? The Christian answer, completely related to Plato’s conviction, is: Man was not created badly at all, but free. He was given the freedom to turn away from God, just like the angels. And if he is punished for it, this punishment is nothing other than justified and therefore good. And the evil that befalls man is not real evil, but merely testing for purification and correction. In the text of the cantata “Ich hab in Gottes Herz und Sinn” (BWV 92) it is said:

“And to you, my Christ,

your anguish and torment, your bitter cross and suffering

for Jesus’ sake be salvation and sugar.”

God creates man, covers him with suffering – merely to test his faithfulness? Really? A deceitful God, and yet a God of goodness? Hard to understand and even harder for preachers to argue his case.

The best of all worlds

The musician Johann Sebastian Bach seems to have been little troubled by these concerns, in contrast to one of his contemporaries who disliked such contradictions so much that he sought to relieve God of responsibility for evil in a very different way: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Leibniz was a universal and astute thinker and mathematician; he invented arithmetic with infinitely small and large numbers, constructed the first calculating machine and wore the most magnificent wig in the world. No wonder, then, that he imagined the Creator God as a mega-Leibniz, so to speak, equipped with a huge calculating machine. He created the world as described in Genesis, but he too was forced to adhere to natural necessity. That is, every action has good and evil in its wake.

The all-good and all-foreseeing God therefore calculated all possible worlds in all details with mathematical precision and thereupon selected from them the optimal one, the best one, the one with the least amount of evil. For Leibniz, creation has become a mathematical optimisation problem, which God solved with flying colours. That is why the proportion of good surpasses the few evils, Leibniz reassuringly asserts, “just as there are incomparably more dwellings than prisons.” And: evil is not real evil – in this he follows Augustine and Luther – but only defective, i.e. deficient good.

Leibniz’s writing, written in elegant French, infuriated a restless spirit, a man of letters and a philosopher: Voltaire, after whom the French named the century before their revolution. In his grotesque satire “Candide”, he accuses Leibniz of naive and clueless optimism, calls him Doctor Pangloss, i.e. a learned all-rounder, and leads him through an earthly panopticon of horror: robbery and torture, murder and desecration, suffering and death are drastically demonstrated to Pangloss. And finally Voltaire provocatively asks: “How! To endure all diseases, to experience all sorrow and vexation, to die a painful death and to fry in hell for eternities to refresh ourselves: all this should be the best fate that could be granted to us? Surely that is not too good for us, and how could it possibly be good for God?”

His questions about the benevolent God remained unanswered – but so did his criticism of man’s morality.

A century later, Jeremy Bentham, whose mummy can still be admired in London, tried to rescue Leibniz’s optimism: For him, the guiding principle of action is “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” of people. However, for him it is no longer God who acts, but man – and his most powerful institution: the state.

And Auguste Comte saw this best world as a future one, describing human progress as a necessary step towards the good – that is, we still have the very best ahead of us. And confidently he proclaimed a new religion: ordem e progresso, order and progress, as we can still read on the national flag of Brazil today. Accordingly, his temples were no longer dedicated to God, but à l’Humanité, to humanity.

Where is God?

The 20th century brought new disillusionment: wars of unimagined proportions swept the world; entire states became prisons. And in the middle of the worst night, a new defender confessed to the good God: “I believe that God can and will bring good out of everything, even the most evil.”

It was the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer who spoke these words. Already imprisoned in a Nazi Gestapo dungeon, he drew on our pious Baroque poet Paul Gerhardt. In his poem “Von guten Mächten treu und still umgeben” he writes for Christmas:

“And hand us the heavy chalice, the bitter one

Of sorrow, filled to the highest brim,

We will take it gratefully without trembling

From thy good and beloved hand.”

But again, someone cries out against this: Elie Wiesel, of Romanian-Jewish descent, imprisoned in another camp between life and death. He describes the unspeakable murder of two adults and a child on the place of execution. “‘Where is God, where is he?” someone asked behind me. Absolute silence reigned throughout the camp. The sun was setting on the horizon. Behind me I heard the same man ask, ‘Where is God?’ And I heard a voice within me answer: ‘Where is he? There – there he hangs on the gallows…'”

In the very last days of the war, the same fate befell Bonhoeffer: he too ended his life naked like Jesus: the former crucified, the latter on the gallows.

What does that mean? For us? Doubt? Despair? At the powerlessness of God? At the wickedness of the world? To complain? Against whom? Against God? Against people? Against which people? The others? The bad ones? Are the others worse than ourselves? Enduring powerlessness, like Bonhoeffer or Voltaire or Socrates, but not as victims but as rebels? Seeking God in powerlessness like Jesus?

Or bravely and piously invoke goodness like Gerhardt? Internalise God and seek him in one’s own soul? Private religion? After all, the modern civil state generously allows us to do that: everyone is allowed to create their own salvation and the corresponding image of God according to their own whim.

The sacred in the encounter

Martin Buber, the Jewish religious philosopher, saw things differently. He tells us to find God with our hearts in the relationship with the Thou, with our fellow human beings, and writes: “The extended lines of relationships intersect in the eternal Thou. (…) People have addressed their eternal You with many names. (…) And what does all erroneous talk about God’s nature and works (…) weigh against the One Truth that all men who have addressed God have meant Himself?”

The limitless Divine opens up in the encounter and is not a defined truth. It cannot be grasped through dogmas, for to define dogmas or principles of faith as truths is to define the divine, to set fines, limits to it. Borders and boundary stones from which walls are built. Walls between people and between cultures. But also: the sacred is not a private salvation. In Buber’s words: “In vain do you seek (…) to limit this you to one that dwells in us (…).”

The Holy and the Human Spirit

Those who travel in Southern Africa are often and abruptly asked which church they attend. Of course, he is not asked about his faith. That is not of interest. And the church itself is not that interesting either. There are countless churches, in the middle of the city and lonely in the savannah, with equally countless names; who wants to know their diverse rites, chants and statutes. No, people ask whether they go to church at all. Going to church is a sign that the foreigner respects the sacred. That which goes beyond him, the individual, and which is contrary to his only private conviction and his only private benefit.

We express quite the same hope – little more consciously – in our appellative Grüezi. Greetings to God, we say, Greetings to God, or: God be with you, dominus tecum, and implore God – and at the same time the stranger: Unite with me in reverence for the same Holy One! And they also mean: Do not rule over me! But rather: Let the Holy One, not the human spirit, rule!

The Holy? The holy is the spiritual that illuminates your spirit. And challenges it to distinguish between good and bad. It is not the divine that is good or bad, nor man, nor even his deeds in the first place, for they are usually entangled in the mundane of everyday life. But their effects are good or bad, and man’s spirit is called upon to consider the good and bad consequences in cooperation and competition – this too is communal, not destructive – and to act according to this caution. Socrates called this spirit that knows about good and evil, conscientia Jerome in the New Testament, Giwizzan, conscience, our Notker, the thick-lipped.

The spiritual to be sanctified is not an invention of Buber, but has been invoked again and again – in this church, of all places, we find the same exhortation: if we look up to the ceiling of the choir, we see the peoples of all continents gathered together – and the prophet Isaiah has God speak: “Turn to me, and ye shall be saved, the ends of the earth: for I am God, and there is none else.” The painter has depicted this spirit as a hidden glow. So also in Isaiah: “Verily thou art a hidden God (…).” However, the Spirit shining and illuminating from the cloud – and uniting us human beings – is not at our arbitrary disposal; it is not tangible and handy, just as our own spirit is not an available organ or instrument, but only proves itself through its human activity.

Literature

– Old Testament, Psalm CVI, V. Translation by Moses Mendelsohn, 1783. Zurich, Diogenes Verlag AG 1998

– Old Testament. The Prophet Isaiah. The Holy Scriptures in Martin Luther’s translation with explanations for the Bible-reading congregation, Stuttgart, Württembergische Bibelanstalt Stuttgart 1974.

– Jeremy Bentham, A Fragment on Government, in: A Comment on the Commentaries amd A Fragment on Government, ed. by J. H. Burns / H. L. A. Hart (The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham), London 1977

– Dietrich Bonhoeffer, After Ten Years. Resistance and Surrender. Letters and Notes from Imprisonment, DBW, Vol. 8. Gütersloh, Gütersloher Verlagshaus 1998

– Auguste Comte, Rede über den Geist des Positivismus, 1842. Translated, introduced and edited by Irving Fetscher, Hamburg, Felix Meiner Verlag 1956.

– Paul Gerhardt, Poems and Writings, Obelisk, Zug 1957

– The Epic of Gilgamesh. 4th plate. Newly translated and annotated by Albert Schott, Stuttgart, Philipp Reclam jun. 1969

– Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Versuche in der Theodicée über die Güte Gottes, die Freiheit des Menschen und den Ursprung des Übels, Felix Meiner Verlag, Hamburg 1996.

– Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Versuche in der Theodicée über die Güte Gottes, die Freiheit des Menschen und den Ursprung des Übels, Felix Meiner Verlag, Hamburg 1996.

– Aryeh Oron, Bach Cantatas website, http://www.bach-cantatas.com/BWV92.htm, 2015

– Plato, The State. German by Rudolf Rufener. Munich, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag 1991

– Voltaire, François-Marie Arouet, Dictionnaire philosophique portatif. Bien, Tout est Bien, 1764. Philosophical pocket dictionary. Everything is good. Translation by A. Ellissen from 1844 www.zeno.org/Philosophie/M/Voltaire/Ueber+den+Satz%3A+%C2%BBAlles+ist+gut%C2%AB

– Voltaire, François-Marie Arouet, Candide oder der Optimismus, 1759. Translated from the French by Ilse Lehmann, Munich, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag 2005.

– Elie Wiesel, The Night. Memory and Testimony. 1958. Translated from the French by Curt Meyer Clason, Freiburg im Breisgau, Herder Verlag 1996

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).