Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten

BWV 093 // For the Fifth Sunday after Trinity

(The man who leaves to god all power) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, strings and continuo

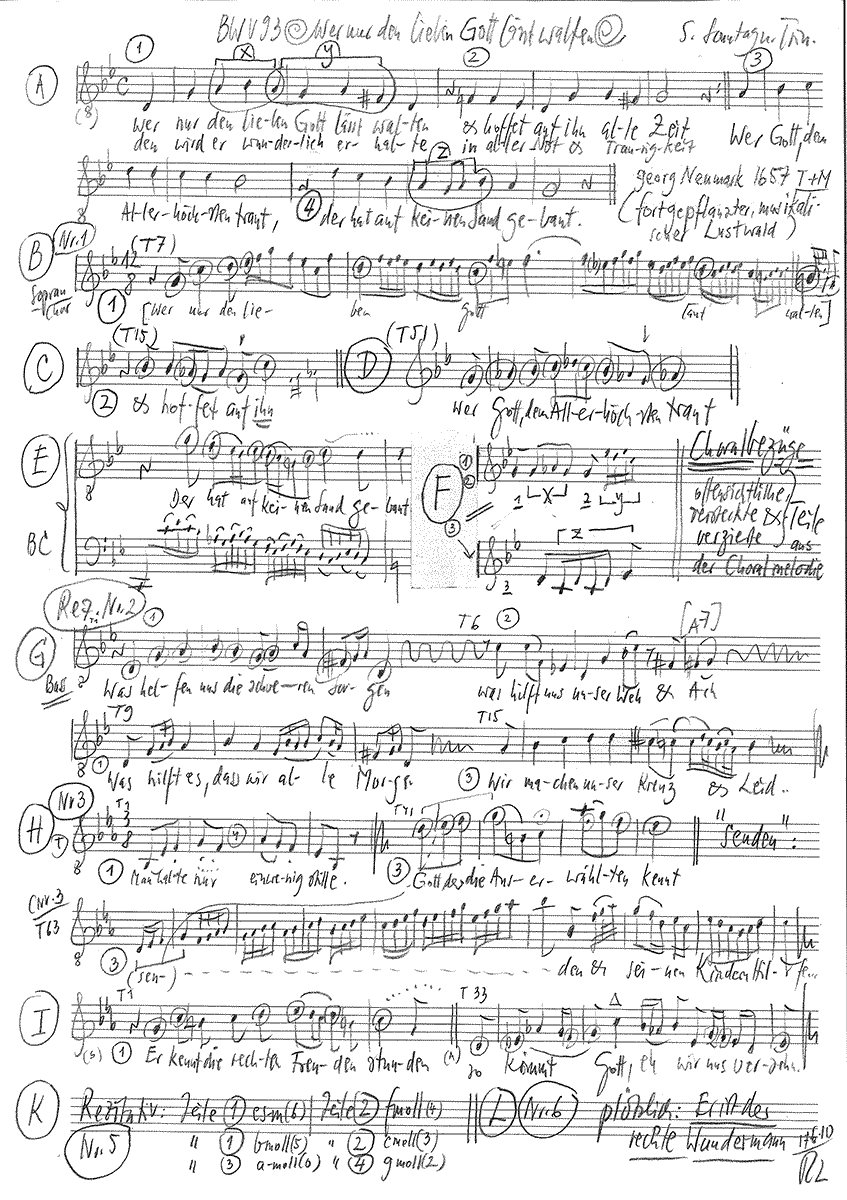

Composed for the Fifth Sunday after Trinity in 1724, the cantata “Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten” (The man who leaves to God all power) at first appears to be a typical representative of Bach’s chorale cantata cycle, employing as it does a traditional church hymn as the musical and textual basis of the work. A second glance, however, reveals that the treatment of the chorale is atypically complex, with chorale melody and text skilfully – and inventively – interwoven throughout the entire cantata. Entirely foregoing da-capo arias, the work has characteristics of a chorale partita (despite the sections of freely versified text), and its concisely structured movements make for a particularly dense and highly convincing composition.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Sohn

Alto

Antonia Frey, Jan Börner, Lea Scherer, Olivia Heiniger, Katharina Jud

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Raphael Höhn

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Oliver Rudin, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Plamena Nikitassova

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Luise Baumgartl

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Michael Von Brück

Recording & editing

Recording date

06/18/2010

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 4, 7

Georg Neumark, 1657

Text No. 2, 3, 5, 6

Arranger unknown

First performance

Fifth Sunday after Trinity,

9 July 1724

In-depth analysis

In the introductory chorus, the forlorn C minor tonality contrasts starkly with the gently rocking 12/8-time siciliano; an expressive interpretation of God’s support and protection through “every cross and sad distress”. Equally notable are the intricate vorimitations, modified line for line, that precede the full choir presentation of each chorale phrase with the melody in the soprano voice. Indeed, it appears Bach wished to give this well-known hymn of comfort a particularly artful arrangement.

The bass recitative effectively conveys the contrast between hymn text and free verse, and thus the sermon-like procedure of textual interpretation. The ensuing aria “If we be but a little quiet, Whene’er the cross’s hour draws nigh”, by contrast, is distinguished by a particular lightness of foot, despite its weighty subject matter. The elegant minuet style imbues the movement with an infectious energy that seems inspired by an image of childlike trust. Even the regular pauses in the string parts do not halt the momentum, but instead provide a musical notion of “psst!” and evoke the energising twists and turns encountered over the course of a life well lived.

The following duet creatively turns traditional chorale treatment on its head: although the soprano and alto deliver the chorale text without amendment, the chorale melody is nowhere to be heard in their short exchanges. Instead, the melody is presented instrumentally as a “chorale without words”, woven into the setting line for line by unison strings. Considering the mastery of this beautiful arrangement, it is no wonder that Bach later reworked it for organ, giving it pride of place in the six “Schübler Chorales”.

This sense of serenity is again succeeded by a chorale recitative of high emotional drama in which Bach brings the alternation between hymn text and interpretive passages, as well as between chorale verse and Sunday gospel, to an emphatic climax. Although “fire and thunder” may crack and the inner “trial by fire” may lead us to despair of God’s mercy, here, the interplay of free continuo passages, unexpected shifts in tempo and harmony, and skilful vocal accents, gives rise to a spirited sermon that no doubt left even the most dynamic preachers of Bach’s time with a hard act to follow.

This mood of spiritual turmoil gives way to an aria for soprano, continuo and oboe, whose energetic trio setting again employs texts from the chorale. Despite its rapid movement, the music cannot entirely cast off its dark fundament; the unfathomable will of God hangs like a shadow of resignation over the song of trust, one textually akin to a hymn of praise to the Madonna.

With a return to the forlorn key of C minor, the resolute closing chorale leads the chorale variations of this cantata to a predictable, yet powerful conclusion. The tenor embellishments and sudden shift to a bright, major tonality in the closing bar provides for a particularly pleasing effect.

Libretto

1. Chor

Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten

und hoffet auf ihn allezeit,

den wird er wunderlich erhalten

in allem Kreuz und Traurigkeit.

Wer Gott, dem Allerhöchsten, traut,

der hat auf keinen Sand gebaut.

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

Was helfen uns die schweren Sorgen?

Sie drücken nur das Herz

mit Zentner Pein, mit tausend Angst

und Schmerz.

Was hilft uns unser Weh und Ach?

Es bringt nur bittres Ungemach.

Was hilft es, daß wir alle Morgen

mit Seufzen von dem Schlaf aufstehn

und mit beträntem Angesicht des Nachts zu Bette gehn?

Wir machen unser Kreuz und Leid

durch bange Traurigkeit nur größer.

Drum tut ein Christ viel besser,

er trägt sein Kreuz mit christlicher Gelassenheit.

3. Arie (Tenor)

Man halte nur ein wenig stille,

wenn sich die Kreuzesstunde naht,

denn unsres Gottes Gnadenwille

verläßt uns nie mit Rat und Tat.

Gott, der die Auserwählten kennt,

Gott, der sich uns ein Vater nennt,

wird endlich allen Kummer wenden

und seinen Kindern Hilfe senden.

4. Arie (Duett Sopran, Alt)

Er kennt die rechten Freudenstunden,

er weiß wohl, wenn es nützlich sei.

Wenn er uns nur hat treu erfunden

und merket keine Heuchelei:

so kömmt Gott, eh wir uns versehn,

und lässet uns viel Gut’s geschehn.

5. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Denk nicht in deiner Drangsalshitze,

wenn Blitz und Donner kracht

und dir ein schwüles Wetter bange macht,

dass du von Gott verlassen seist.

Gott bleibt auch in der größten Not,

ja gar bis in den Tod

mit seiner Gnade bei den Seinen.

Du darfst nicht meinen,

daß dieser Gott im Schoße sitze,

der täglich, wie der reiche Mann,

in Lust und Freuden leben kann.

Der sich mit stetem Glücke speist,

bei lauter guten Tagen,

muß oft zuletzt,

nachdem er sich an eitler Lust ergötzt:

«Der Tod in Töpfen!» sagen.

Die Folgezeit verändert viel!

Hat Petrus gleich die ganze Nacht

mit leerer Arbeit zugebracht

und nichts gefangen:

auf Jesu Wort kann er noch einen Zug erlangen.

Drum traue nur in Armut, Kreuz und Pein

auf deines Jesus Güte

mit gläubigem Gemüte.

Nach Regen gibt er Sonnenschein

und setzet jeglichem sein Ziel.

6. Arie (Sopran)

Ich will auf den Herren schaun

und stets meinem Gott vertraun.

Er ist der rechte Wundersmann,

der die Reichen arm und bloß

und die Armen reich und groß

nach seinem Willen machen kann.

7. Choral

Sing, bet und geh auf Gottes Wegen,

verricht das Deine nur getreu

und trau des Himmels reichem Segen,

so wird er bei dir werden neu;

denn welcher seine Zuversicht

auf Gott setzt, den verläßt er nicht.

Michael von Brück

“Roots of Hope and Serenity”

Thirty years of war. Thirty years! Who only lets the good Lord prevail? Half of Central Europe destroyed, pillaging, devastation, rape, half the population wiped out. Who only lets the good Lord prevail? The poet, Georg Neumark, does not ask this question in this song around 1657. Paul Gerhardt (1607-1676) is another who wrote poetry at this time. He too creates songs of beauty, joy, trust in God – hardly a trace of the horror of the times. Johann Scheffler, the “Silesian Angel” (Angelus Silesius) – whom we will come to later – is contemporary (1624-1677).

What moved these people in that age, who went through such horrors and yet could sing of God’s goodness? Later centuries were no longer able to do so. There is a parody of the cantata BWV 93 from the end of the 19th century that was included in the Workers’ Songbook of 1894. The text was written by a Max Kegel. I would like to recite only two stanzas: “He who only lets God rule / and pays taxes all the time, / will wonderfully receive / the favour of the high authorities. / He will not be sent out to the city as a democrat / in holy timidity. / Therefore, always walk in God’s ways / and only do faithfully / everything that is imposed on you, / even if you have to go hungry. / Then the law’s word / will not turn you away from the police state.”

That is the mood at the end of the 19th century. And the 20th century will then – in just twelve years of tyranny in Germany and a few years more in Russia – exceed many times over the number of victims that we have to imagine in the face of the Thirty Years’ War. And today? Technology has advanced so far that we could probably magnificently increase the number of victims again in just a few minutes. Who only lets the good Lord prevail? The poet of this song, Georg Neumark, was a lawyer and was pushed through half of Europe – he is connected with Königsberg and Thuringia, also with Kiel. He is sent about in a battered continent.

Bach, who later sets this text to music, writes in a different environment. He himself is not entirely happy with his respective authorities, but he is doing okay. Shortly before, there had been the premiere of the mighty St John Passion in Leipzig and, as I will show, there is a spiritual closeness to its final chorale. Immanuel Kant was born shortly before this cantata was premiered. Peter the Great appoints Catherine as co-regent, and the University of Petersburg is founded. A different environment, no doubt.

The age in which Bach lives is an age of hope. The Baroque transports the promises of heaven into this world. The churches are painted accordingly. But even this hope is not cheap. Those who lived through the Seven Years’ War and all that was to follow know this. Hope is not cheap. It requires inner strength and has a root in corresponding experience. And that is precisely what the cantata “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten” is about. Hope is, if we formulate it somewhat abstractly, the difference between what we perceive experientially and what our imagination can shape as a better world. Hope is not a promise of a never-never day, but the power to act out of inner movement.

Religion has two roots. One root reaches deep into the experience of suffering, religion is then a means of compensation, of coping with suffering. Religion keeps alive the hope that there might be something else beyond this suffering, something that ultimately provides meaning even for the suffering. But this question can only be answered if one recognises the second root of religion, and that is ecstasy. The ecstasy of experiencing beauty, of love in the world. And it depends on the open eye and ear and the other senses to be able to experience these ecstasies. People like Francis of Assisi or Paul Gerhardt sing ecstatically in the face of a sunrise. Mozart composes joy in all circumstances, especially when he is not feeling well. Bach sits in his narrow Thuringian-Saxon world and hears the heavenly music that catapults him out of this confinement. He writes almost non-stop, also to earn money, certainly. But what he writes down is “ec-static”, it stands beyond all limitations. Hope, then, is not a cheap consolation, but is rooted in the experience of the ecstatic. There is a wise word by the Czech poet, writer and later President of the Republic, Vaclav Havel. He says: “Hope is not optimism, it is not the belief that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something has meaning, regardless of how it turns out.” In other words, not the blind, unsuspecting comforting of “it will be all right”, but the certainty that it has a meaning, regardless of how it turns out. A few days ago, I had the opportunity to revisit the – I would like to say – heroes of 20 July 1944: Stauffenberg, Goerdeler and others. There it becomes clear: hope is acting with the certainty that it has a meaning, regardless of how it turns out.

This cantata speaks of “Christian serenity”. What is that? We already have enough difficulties spelling out what serenity is – and then: Christian serenity? That is precisely the theme of this cantata: What is serenity, where does it come from? In the face of this suffering, which Bach composes in a warning manner and intensifies in comparison to the song text, how can serenity enter here? Bach’s librettist, whose name we don’t know, overdoes it all in a baroque manner, inserting sweet words into the massive choral text. Bach, however, feels very clearly that he must compose out the suffering, the cross that man bears, and only then make clear the root of Christian serenity in the rhythm, tone and melody of the text. In the fifth stanza it says: “The following time changes much! (…) and sets a goal for each.” What is the goal, what is the meaning of suffering? Sense, this German word, is originally a word of direction, a change of place. We still know it in the word “clockwise”.

Movement is change in time. So sense also indicates a direction in time: From present experience to a better world, imagined through fantasy. Hope consists in understanding this fantastic not only as a better possibility, but as a guide to action.

Those who hope use their imagination to put it into practice in life. This is always a personal experience, and it seems to me that Bach implements this insight musically not only in this cantata but in many other of his sacred choral works in such a way that he first lets the solo voices, or in this case the figurative voices of the choir, sing and only then lets the congregation respond in chorale-like fashion. This means that the individual experience is necessary first, so that the confession and the action of the community then become possible. This corresponds to the feeling of the Baroque, namely that the experience must come from the heart, from a transformed consciousness. It is the individual experience of faith that is then shared together. The first movement of the cantata expresses this in a gesture of joyful trust. Playful and yet plaintive. In the solos, initially figurative, then unshakable and full of certainty, even confessional in the cantus firmus: hope always. A heading not only for the musical events to come, but for life. Playful and lamenting, the gesture of joy and the gesture of sorrow at the same time. I will come back to this at the end of my remarks. Here already it becomes clear: it is Christian serenity that rises above pain and sadness. Christian serenity is not a looking away, not a turning away from the world – that is forbidden by the experience of the cross, however we interpret it in detail. It is not a looking away from what happened in the Thirty Years’ War and was to follow terribly in all later times, which also shapes our sorrowful present today. Rather, it is a looking, but from the experience of the nevertheless or the nonetheless. As Bach wonderfully set to music in his chorale motet “Jesu meine Freude”: “Trotz, trotz dem alten Drachen” and in this “trotz” defiance is also expressed. Defiance against violence and especially against stupidity in the world. Because violence has one of its strongest roots in stupidity. I cannot justify or elaborate on that here.

Bach feels in this music what we can perhaps call the “serene power of silence”. “Just hold still a little”. The melody is built at the beginning from the intervals of the chorale melody “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten”, but it then plays along in a relaxed manner. The serene power of silence is a smiling silence. That is something different from a rigid silence. And how you get from a rigid silence to a smiling silence is the epitome of what we call spirituality today.

Here on the vaulted ceiling of the Trogen church we have a painted commentary on this: “Let the children come to me,” says this picture right here above us. And this is an experience not only of the Christian world and Christian serenity, but we also know the motif from Indian and Chinese cultures in a similar way. It is the child’s ability to weep bitterly, to be comforted and from one minute to the next to start anew and playfully rediscover the world, to engage anew. It seems to me that this is what is set to music in this wonderful music.

Serenity, “Christian serenity”. The joy of playing is expressed in the duet, in the wonderful melodic dance between oboe and soprano, supported by the sonorous bassoon. It is like a graceful play in the heavens. For me, this sixth part is the climax of the cantata. The self-revelation of trust: “I will look to the Lord and trust in my God always.”

Indeed, this is a graceful heavenly play. The word we have for it in the German language and in theology is “grace”. But in the original Greek text, the word here is “charis”. But “charis”, which we translate as grace, is an aesthetic term. It comes from the Greek theatre and is linked to the Charites, the Greek goddesses of grace, dance and music. Only later in the Latin translation as “gratia” did it become a legal term, unfortunately. In the Greek, in the New Testament therefore, it is a term of grace. And when we hear this grace at play again and again in Bach’s music, grace is composed as a graceful beauty that touches us deeply. Bach usually has the woodwinds play, which we hear in duets with soprano solos, or they are duets between the solo voices. The angelic soprano voice is always there (think of the moving duet of soprano and bass “Herr dein Mitleid, dein Erbarmen, tröstt uns und macht uns frei” from the Christmas Oratorio) and then Bach sets the serene grace of grace to dance rhythms. So too here, in this cantata. That is the reason for trust. And so at the end, in his final chorale, Bach comes to “sing, pray, walk and trust”. Then God is present – and we have already heard in the introduction to the concert that the Benedictines’ “pray and work”, the “ora et labora”, is joined by the “canta”, the “sing”. That is the gesture of this last verse. I have already indicated that there is a spiritual relationship here to the final chorale of the St John Passion. For there, after the drama of Jesus’ suffering and passion, it says at the very end, in the last line: “I will praise you forever”. This is the song of the redeemed human being who has gone through suffering and now dances serenely in the grace of grace.

Thirty years of war, searching for trust, searching for hope and above all for the certainty of hope. That is the theme of this cantata. Angelus Silesius, the contemporary, writes about this in many of his wonderful aphorisms. In the “cherubic wanderer”, for example, he says: “God dwells in a light to which the path is broken. He who does not become it himself does not see him eternally.” Or another verse, with a similar mystical meaning: “If Christ is born a thousand times in Bethlehem, and not in you, you will still remain eternally lost”. It comes down to the inner transformation. It is not something that somehow comes or does not come, but it is task. It is the task of man to deal with his experiences, with his consciousness in such a way that he breaks through to this inner dimension of ecstasy and joy, from which he can then act. Christian serenity, we said, is not looking away, but looking towards, but even more looking through. Looking through to the deeper rhythms, to the deeper harmonic laws that lie behind our superficial, torn world. And the world is superficial and torn apart because we don’t look. It is the sick, torn heart that acts with violence. But a heart that can be serene, because it allows itself to be touched by the heavenly impression, acts in joy and love.

One last remark: what will remain of our culture, of our religion or religions? In five thousand years, in ten thousand years perhaps? We look back on three hundred years of music history when we experience Bach and make music. We look back on two thousand years of Christian history when we experience this passage, this looking through the cross towards Christian serenity. We look back on two and a half thousand years of Buddhist history when we learn to systematically practise serenity, when we train our senses and our consciousness to open up to what Bach sings and plays about. Two thousand years, three thousand years – that seems a lot to us, but it is only a short episode in the history of humanity, which is decades thousands, centuries thousands old. If we look back into the depths of this dimension of time, we know almost nothing. If we look five thousand years, ten thousand years ahead, we know nothing either. But one thing is certain: our cultures, our religions will have changed dramatically by then, provided humanity has not wiped itself out by then. We are already experiencing the rapid change within the few decades of our own lifetimes. It seems to me – but this is my own personal judgement which cannot be generalised – that one thing remains of this Christian experience, of Christian serenity: the music in which the contrasting experience of pain and joy resounds as nowhere else in human expression. It is what we hinted at earlier, what is present in the music of Bach, of Mozart and of many others, but perhaps especially in these two: that joy and sorrow, being redeemed and pain sound together at the same time. In the cantata, this can be heard and experienced crystal clear in the various figures, in the first but also in the second movement. Joy and sorrow are not two successive gestures of the human heart, but they are mutually dependent, they play around each other. And when one has understood this, when one has experienced this, then a certainty of trust is possible.

One of the great conductors of the 20th century, Sergiu celibidache, said:

“Bach is what remains when one has overcome suffering.”

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).