Was frag ich nach der Welt

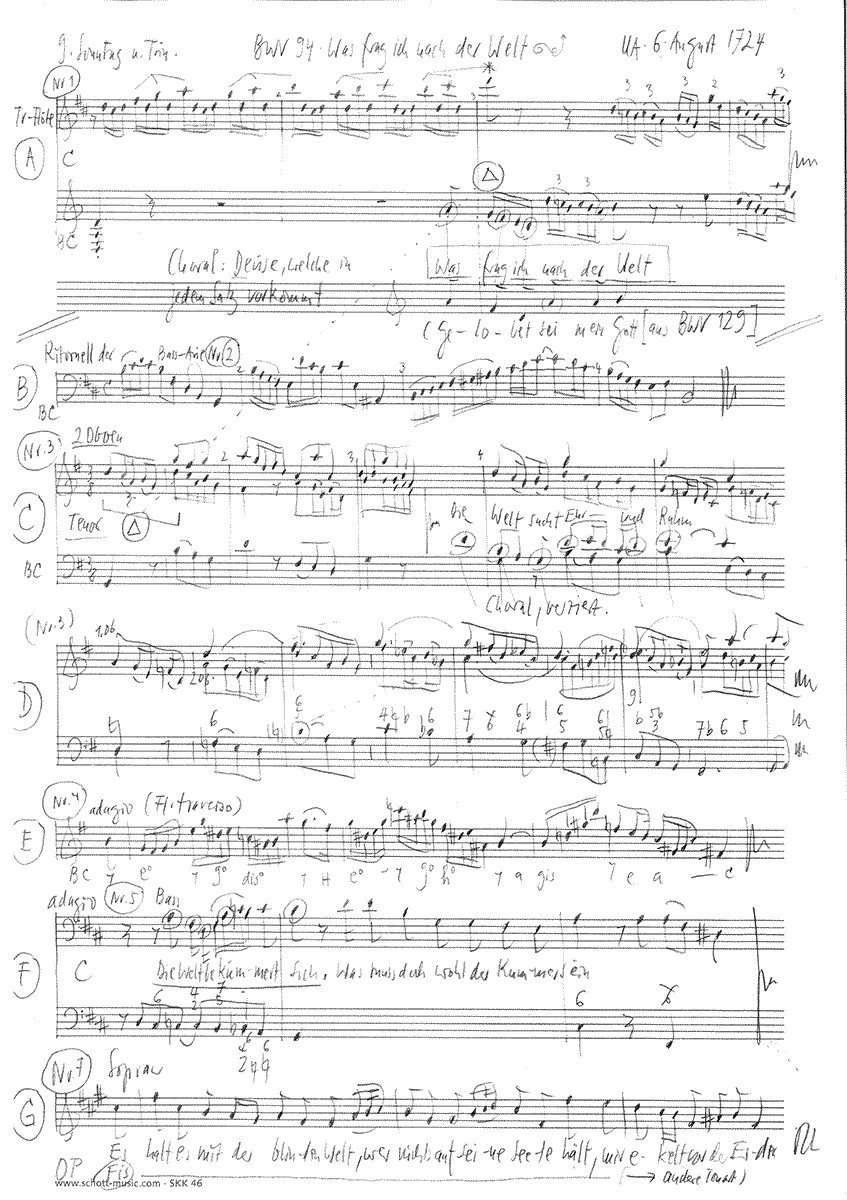

BWV 094 // For the Ninth Sunday after Trinity

(What need I of this world) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and basso continuo

It would be a disservice to the cantata “Was frag ich nach der Welt” (What need I of this world), composed for the Ninth Sunday after Trinity in 1724, were we to misconstrue it as a conventional example of a Protestant renouncement of the earthly world. After all, the composition is replete with subtle arguments and messages that inspired Bach to sensitive and original compositional solutions.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber, Raphael Höhn, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Valentin Parli, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen, Christine Baumann, Eva Borhi, Christoph Rudolf, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone, Peter Barczi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Transverse flute

Marc Hantaï

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Manfred Papst

Recording & editing

Recording date

08/15/2014

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 3, 5, 8

Balthasar Kindermann (1664)

Text No. 2, 4, 6, 7

Rearrangement by an unknown writer

First performance

Ninth Sunday after Trinity,

6 August 1724

In-depth analysis

The introductory chorus, with its concertante flute part and light-footed orchestral accompaniment, contains no strains of worldly angst and futility, but rather of clear-sighted joy and resolve. Indeed, few settings by Bach are more suited to eschewing the tone of solemnity that often weighs on Bach performances and to revealing the original vigour of his work. The choral insertion, with its clear, block-like entries, is enhanced by subtle details such as the low pedal notes after the words “Thou, thou are my repose” that are particularly effective in this translucent setting.

The bass aria opens with an expansive continuo gesture that lends substance to the words of the soloist, whose song is more akin to a reflective soliloquy than a thundering sermon. It is the voice of a worldly-wise sage who knows the perpetual “breaking and falling” of human hopes and thus seeks solace in Jesus, whose constancy is underscored in the music. Propelled by the ostinato-style continuo line, the aria intensifies towards the conclusion: the final line “what need I of this world” is presented less as a question than as a clear renunciation of the world.

The tenor recitative, which links elaborate chorale lines accompanied by flowing woodwinds with plainer recitative insertions, proffers a catalogue of foolish earthly notions that are gradually revealed to be hollow. Among their Leipzig acquaintance, Bach and his librettist appear to have closely observed those who strutted around self-importantly and built their vain “tower of pride”; it is thus all the more shocking when the soloist drastically declares how quickly it all can end: the “wretched earthly worm” cannot be saved by such worldly display – all pomp vanishes in the grave! The bitterness of this realisation can be heard in the laboured bel canto of the third chorale line; it is then the gentle introduction of Jesus’ name that helps the narrator to alter his perspective and accept rejection of the world as a stance befitting the faithful Christian.

The following alto aria, an adagio meditation, is lent a wan tone of transience by the obbligato transverse flute; in this lament on the blindness of human beings, the pain-filled vocal line continually breaks off in grief and disappointment. The swift middle section then describes the determination to choose Jesus over vain Mammon – a promise that is celebrated in a touchingly slow transition section ere the short da-capo dispenses with the “deluded world” once and for all.

In the bass recitative, Bach continues his interpretation of the chorale. Once again, the soloist presents a delicately ornate melody while a chromatically descending continuo line underscores the pervading mood of affliction and contempt. Throughout the discursive recitative insertions, however, a new attitude emerges that presents these torments as the result of self-inflicted entrapments – for which mankind, in view of God’s divine gifts, can only feel shame. When the accompanying figure begins an ascent on the words “I suffer Christ’s disgrace”, a more healing interpretation of worldly suffering emerges that finds its purpose in identification with the Saviour.

The turning point thus achieved, the tenor embarks on a lively aria in 12/8 metre whose compact accessibility is reminiscent of Telemann. The underlying tone is one of ridicule of the glaring self-worship of those who, like blind moles, dig for worthless treasure while ignoring the riches of heaven. In this somewhat zealous music of converts, we can almost see a reformed junkie who remembers all too clearly what he has put behind him.

It is not surprising, then, that the following soprano aria presents a more subdued confession of faith, with the warm oboe d’amore line accompanying the vocalist like a comforting kindred spirit. Here, the tender albeit somewhat dry motive may be seen as a nod to the “travails of the plains” entailed in a life of virtue.

In a powerful four-part setting, the closing two-verse chorale cuts to the heart of the cantata’s message: all possessions of the world cannot “put pallid death in bondage”; mankind’s surest investment remains trusting in the heaven attained through Jesus.

Libretto

1. Chor

Was frag ich nach der Welt

und allen ihren Schätzen,

wenn ich mich nur an dir,

mein Jesu, kann ergötzen!

Dich hab ich einzig mir

zur Wollust fürgestellt,

zur Wollust vorgestellt,

du, du bist meine Ruh:

Was frag ich nach der Welt!

2. Arie (Bass)

Die Welt ist wie ein Rauch und Schatten,

der bald verschwindet und vergeht,

weil sie nur kurze Zeit besteht.

Wenn aber alles fällt und bricht,

bleibt Jesus meine Zuversicht,

an dem sich meine Seele hält.

Darum: Was frag ich nach der Welt!

3. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Die Welt sucht Ehr und Ruhm

bei hocherhabnen Leuten.

Ein Stolzer baut die prächtigsten Paläste,

er sucht das höchste Ehrenamt,

er kleidet sich aufs beste

in Purpur, Gold, in Silber, Seid und Samt.

Sein Name soll für allen

Sein Name soll vor

in jedem Teil der Welt erschallen.

Sein Hochmuts-Turm

soll durch die Luft bis an die Wolken dringen,

er trachtet nur nach hohen Dingen

und denkt nicht einmal dran,

wie bald doch diese gleiten.

Oft bläst uns eine schale Luft

den stolzen Leib auf einmal in die Gruft,

und da verschwindet alle Pracht,

wormit der arme Erdenwurm

hier in der Welt so großen Staat gemacht.

Ach! solcher eitler Tand

wird weit von mir aus meiner Brust verbannt.

Dies aber, was mein Herz

vor anderm rühmlich hält,

was Christen wahren Ruhm

und wahre Ehre gibet,

und was mein Geist,

der sich der Eitelkeit entreißt,

anstatt der Pracht und Hoffart liebet,

ist Jesus nur allein,

und dieser solls auch ewig sein.

Gesetzt, daß mich die Welt

darum vor töricht hält:

Was frag ich nach der Welt!

4. Arie (Alt)

Betörte Welt, betörte Welt!

Auch dein Reichtum, Gut und Geld

ist Betrug und falscher Schein.

Du magst den eitlen Mammon zählen,

ich will davor mir Jesum wählen;

ich will dafür

Jesus, Jesus soll allein

meiner Seelen Reichtum sein.

Betörte Welt, betörte Welt!

5. Rezitativ (Bass)

Die Welt bekümmert sich.

Was muß doch wohl der Kummer sein?

O Torheit! dieses macht ihr Pein:

im Fall sie wird verachtet.

Welt, schäme dich!

Gott hat dich ja so sehr geliebet,

daß er sein eingebornes Kind

vor deine Sünd

zur größten Schmach um deine Ehre gibet,

und du willst nicht um Jesu willen leiden?

Die Traurigkeit der Welt ist niemals größer,

als wenn man ihr mit List

nach ihren Ehren trachtet.

Es ist ja besser,

ich trage Christi Schmach,

solang es ihm gefällt.

Es ist ja nur ein Leiden dieser Zeit,

ich weiß gewiß, daß mich die Ewigkeit

dafür mit Preis und Ehren krönet;

ob mich die Welt

verspottet und verhöhnet,

Ob sie mich gleich verächtlich hält,

wenn mich mein Jesus ehrt:

Was frag ich nach der Welt!

6. Arie (Tenor)

Die Welt kann ihre Lust und Freud,

das Blendwerk schnöder Eitelkeit,

nicht hoch genug erhöhen.

Sie wühlt, nur gelben Kot zu finden,

gleich einem Maulwurf in den Gründen

und läßt dafür den Himmel stehen.

7. Arie (Sopran)

Es halt es mit der blinden Welt,

wer nichts auf seine Seele hält,

mir ekelt vor der Erden.

Ich will nur meinen Jesum lieben

und mich in Buß und Glauben üben,

so kann ich reich und selig werden.

8. Choral

Was frag ich nach der Welt!

Im Hui muß sie verschwinden,

ihr Ansehn kann durchaus den blassen Tod nicht binden.

Die Güter müssen fort,

und alle Lust verfällt;

bleibt Jesus nur bei mir:

Was frag ich nach der Welt!

Was frag ich nach der Welt!

Mein Jesus ist mein Leben,

mein Schatz, mein Eigentum,

dem ich mich ganz ergeben,

mein ganzes Himmelreich

und was mir sonst gefällt.

Drum sag ich noch einmal:

Was frag ich nach der Welt!

Manfred Papst

Remediation of restlessness

The text of the cantata “Was frag ich nach der Welt” is about the great paradox of human existence and its overcoming: We are in the world, but have no power over our lives. The remedy is not vanity, but repentance and faith.

The world is smoke and shadow. How quickly it has disappeared! And we with it. Man is nothing but an earthworm, whether he builds palaces for himself, whether he walks in purple, velvet and silk or adorns himself with gold and silver. He may strive for fame and glory, occupy the highest offices and build himself a tower of pride that reaches to the clouds: In the end, it is all nothing.

A stale breeze is enough to blow our proud bodies into the tomb all at once. Then all the splendour with which we have made so much state disappears. Good and money prove to be vain trinkets. Already in the Old Testament, in Kohelet 1.2, we read that everything is vain. Vain, futile, meaningless: this is how Luther understands the word.

We are fools. We allow ourselves to be beguiled. We realise too late that the pleasure and joy of the world are nothing but deception. Like a mole, we have burrowed blindly into the ground and found only excrement, forgetting about heaven.

These are linguistic images of baroque power. They all come from Bach’s cantata “Was frag ich nach der Welt”. Of course, vanitas motifs have permeated our religious and philosophical history since Jeremiah and Plato. Already in ancient art, then especially since the Middle Ages, we encounter pictorial representations of vanitas – often in the form of skulls, skeletons, hourglasses, scythes. Sic transit gloria mundi: this is the general bass of human history.

It feeds on an omnipresent paradox: we are in the world as human beings, but we have no power over our lives. Death is certain, but its hour is uncertain. We are in God’s hands and equally exposed to the end with every breath. Sometimes we feel like masters of the earth. Often we act like it. But it is all lies and deception. We are thrown into life and therefore remain homeless. We are restless on the road, torn between fear and hope, between self-confidence and despondency.

But this is not the last word. At least not the last word of our valiant cantata poet Balthasar Kindermann, who was born in Zittau in 1636 as the son of a sword sweeper and later became a master of theology, poeta laureatus, and even a member of the Order of the Elbe Swan. The author of satires, dramas, rhetorical writings and poems, married to the daughter of a Swedish captain and father of six children, died in Magdeburg in 1706. Johann Sebastian Bach was 21 years old at the time. The cantata we are concerned with today was composed by the master 18 years later, at the age of 39, for the 8th Sunday after Trinity, 6 August 1724. The text of the opening and closing chorale was taken over verbatim by Kindermann; parts two to seven were revised for the composition by an unknown hand.

“Was frag ich nach der Welt” (“What do I ask about the world”): our text begins with this cheeky phrase, half exclamation and half question. It could well stand on its own, as the philosophical conclusion of an independent mind. One can imagine it pronounced in very different ways: equanimously or challengingly. But of course we are moving here in a Christian and, more closely, liturgical context, and so the six memorable words find their songlike continuation:

“What do I ask of the world

and all its treasures

if I can only delight in you,

my Jesu, I can delight in.”

Earthly and heavenly treasures

In this context, the impure rhyme “Schätzen/ergötzen” is of particular charm. It may have its specific linguistic or dialectal historical reasons and may not always have been perceived as impure, but it also seems to us today to be a sign of a tiny but nevertheless significant shift: The two terms fit together, but they are not congruent. There are earthly and heavenly treasures. What Jesus gives us is of a fundamentally different kind than what the world can offer us. Eduard Mörike, the Swabian late Romantic poet and Protestant pastor, would have enjoyed this little play of diphthongs.

The message of the double verse is made clear to us once again in the second quatrain of the first choral stanza:

“Thee only have I

for lust,

You, you are my rest:

What do I ask of the world.”

What moves us here is the one-in-one thinking of lust and tranquillity, of emphasis and contemplation: he who directs his delight and desire towards heavenly, not earthly treasures, attains not only fulfilment but also tranquillity. Spiritual passion, which shows itself in the double vocative of “you”, already carries its own overcoming. It opens up a state for the soul beyond the earthly restlessness that so dominates our hectic everyday life, but it does so without lapsing into stoic, dull equanimity. The music takes up this tension wonderfully; the intimate simplicity of the chorale movement and the sustained calm of the orchestral parts are contrasted by the flute part as an image of cheerful bustle.

The bass aria that follows deepens the statement of the opening chorale, surprisingly in seven instead of eight verses, the first three rhymed: With the metaphors of the world as smoke and shadow, central motifs of the vanitas imagination are quoted. They are widespread in German Baroque poetry, especially in the poems from the time of the Thirty Years’ War, which Kindermann experienced as a boy and which is also the high period of German hymnody. The line can be drawn from there via the pastor’s son Gottfried Benn to Bertolt Brecht, who once said: “What will remain of these cities is the wind that passed through them!

Vanity on earth

Smoke and shadow are joined by ashes, dust and bones in Baroque poetry, for example in Andreas Gryphius’ 1643 sonnet “Es ist alles eitel”, which I quote here as a masterpiece pars pro toto:

“You see, wherever you look, only vanity on earth.

What this man builds today, that man will tear down tomorrow;

Where cities stand now, there will be a meadow,

Where a shepherd’s child will play with the flocks.

What blossoms splendidly now shall soon be trampled underfoot.

What now throbs and defies will be ashes and bones tomorrow.

Nothing is eternal, no ore, no marble stone.

Now happiness laughs at us, soon complaints thunder.

The glory of high deeds must vanish like a dream.

Shall then the game of time, the light man pass?

Alas! What is all this that we think delicious?

as a vile trifle, as a shadow, dust, and wind,

as a flower of the meadow that cannot be found again.

Nor will any man contemplate what is eternal.”

Two decades later, Balthasar Kindermann was still living in this imaginary world. But the poeta minor does not stop at the world as smoke and shadow, but opposes it with a better, a heavenly life:

“But when everything falls and breaks

Jesus remains my confidence,

in whom my soul clings.

Therefore, what do I ask of the world!”

In the third part of the cantata, this thought is again further unfolded. Here we find the apt caricature of the “lofty people” and especially of the man with his pompousness, his striving for office, his tower of pride, which is supposed to reach up to the clouds. Of course, this is reminiscent of the Tower of Babel and of human notions of omnipotence, to which the Old Testament God reacted with the punishment of confusion of language. We are all reminded of the epochal painting by Pieter Brueghel from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, painted in 1563, a symbol of the hubris not only of our modern times.

Did Kindermann know it? We do not know. But we trust that there is more to works of art than their creators know – and that they sometimes enter into a spiritual conversation with each other. Our cantata in particular shows us this. In Aria No. 2, which speaks of the world as smoke and shadows, Bach congenially traces the unsteadiness, the fleeing and wavering of these elements; and in Aria 4, which is about the “beguiled world”, the “false appearance” is virtually mocked in the trill of the traverse flute. Then, when counting the mammon, we even hear the jingling of coins in an increasing cadence. Whether the composer was aware of this or not, the text led him to this fascinating interpretation.

Sliding things

In the tenor recitative, we come across another remarkable formulation. The ambitious one, we hear,

“seeks only high things

and does not even think

how soon they slip away.”

“Things glide”: that’s what it says without any addition. We do not know whence and whither they glide. Kindermann himself wrote it that way, not his unnamed editor. The phrase is irritating because it seems so modern. “Things glide”: This could almost be a programmatic sentence of classical modernism with its basic feeling of existential uncertainty, comparable to Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s metaphor of concepts decaying in people’s mouths like musty mushrooms. But this experience obviously existed three centuries earlier. What a figure of speech!

However, I do not want to claim that the text of Bach’s 94th Cantata is a masterpiece. It also has its weaknesses. Like many cantata texts, it tends to be somewhat clichéd. After the powerful exposition in the tenor’s recitative, there is some liturgical word-beating; time and time again, what we already know is hammered into us: The believer banishes vain trumpery from his breast. Jesus alone keeps his heart glorious “before others”, gives it true honour, snatches it from vanity. The phrase “before others” itself contains a moment of arrogance. This is not a phrase that fits the commandment of Christian humility. A Christian man should not exalt himself above others. Otherwise, he too will be caught up in vanity.

The world is infatuated. So says the alto aria. And it captures the word in all its double meaning. We hear a graceful female voice. She complains about the false appearance of the evil world, she confesses to Jesus alone. Nevertheless, a subtle contradiction arises in the tension between text and music – here and then again in the delicious soprano aria no. 7. There is something iridescent about the chaste confessions of the female singers. They lament the beguiled world and at the same time celebrate it in its sensual euphony. Here we hear not the voices of disembodied angels, but those who increase the beauty of the world by praising it.

Remediation in faith

The world, repeatedly seen by the cantata poet as a person, as it were as a seductive but also corruptible “Frau Welt”, as we know her from the cathedral at Worms, is distressed. She sees herself unjustly exposed to contempt. But for this sorrow she should now be ashamed. For Jesus has done her so much good that it would only be right and just if she were to suffer without complaint for his sake. In the horizon of salvation history, she has no claims to make, for her suffering only takes place in time. Redemption, however, has its place in eternity, which is not simply an extension of time, but a category sui generis. The believer has to answer to it; if the world mocks and disregards him for it, he need not worry. He knows that it is only a delusion. In the tenor aria no. 6, the drastic image of yellow excrement appears, which the burrowing mole finds “in the grounds” while he forgets about heaven. This phrase evokes not only earth, ashes and dust, but also the reasons of reason, which are not those of faith. The mole man digs in the wrong place. The soprano aria that follows has an almost anaemic, detached effect:

“Es halt es mit der blinden Welt,

who holds nothing on his soul,

I am disgusted with the earth.”

“Repentance and faith” are recommended here as a remedy; in love for Jesus alone lie riches and bliss. Of course, here too the sensual beauty of the music counters the doctrine of renunciation.

The final chorale once again takes up two authentic eight-line stanzas by Kindermann, bracketed by the verse “Was frag ich nach der Welt”. “In the Hui it must disappear”, it says. This formulation baffles us today. “In the Hui”: was this modern and casual phrase actually already common in 1664? We are surprised to hear it. But it is indeed an old word; the industrious brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm have found plenty of evidence for it, not least in the Zurich Bible.

The text of Bach’s 94th cantata is heterogeneous. It is composed of song verses by Balthasar Kindermann and additions by an unknown later arranger. Certainly we may assume that the composer, as Wolfgang Hildesheimer recorded in his late lecture “Der ferne Bach”, “regarded the texts for his cantatas as something given and not as something to be judged”. Yet the words may be patchwork: The cantata is of one piece. Here, once again, the miracle occurs that we so often encounter in Bach: the transformation of time-dependent material into timeless art. The composer combines depth of thought, mathematical precision and sensual richness. He is a genius of polyphonic invention, but also a genius of translating religious ideas into pure sound.

The philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz once formulated a memorable definition of music. He described it as an “arithmetical exercise of the soul, whereby the soul is not aware that it is counting”. Bach could not be better characterised. In him, crystalline clarity and baroque fullness of life are combined. Bach knew the secrets of numbers and the architecture of heavenly arithmetic as well as the abysses of life, suffering and faith. He shaped them in the millennium work of the “Mat- thäuspassion”. “An apparition of God: clear, yet inexplicable”: that’s what the good Zelter called him in a letter to Goethe. But he was also a lively everyday man. A husband and family man who strove for happiness and knew comfort, even though he had to watch several of his children die, a church musician involved in a thousand duties and hardships. As a letter-writer, he was usually long-winded and formal, but at times he was a man of bearish humour.

“To have as if one had not”.

We started from the vanitas mundi. It shaped Johann Sebastian Bach’s thinking and composing. But it did not make him unfaithful to the beauty, diversity and dignity of creation. In contrast to the statement in Aria No. 7, Bach was not disgusted by the world, but celebrated it in the Ernst Bloch sense of the word as the pre-shine of the eternal in his music. As a deeply religious man, he also understood that wisdom which we know from the Bible as later from Theodor Fontane’s novel “Der Stechlin”: Whoever wants to live happily in the face of the finiteness of life must strive for something paradoxical: for a “having as if one had not”. After a loving, reverent participation in the fullness of creation – in full knowledge of its and one’s own transience, perhaps even futility, and thus without any attitude of entitlement. That is why Bach’s music is still alive before us today. It embraces heaven and earth. In the final chorale it is said:

“What do I ask of the world!

My Jesus is my life,

my treasure, my possession,

To whom I surrender

My whole kingdom of heaven

And whatever else pleases me.

Therefore I say again:

What do I ask of the world!”

“My whole kingdom of heaven / and whatever else pleases me”: This is a phrase as confusing as it is gratifying: for it shows that the kingdom of heaven is not closed to earthly life. There is also room for “whatever else pleases me”. It is not about renunciation, but about fulfilment.

“What do I ask of the world” – the question moves and shakes, but it also liberates us, especially since we have learned to understand the hereafter also as an inner treasure. In the unprecedented acceleration of our lives, nothing is more necessary than reflection and retreat. On this path, we may even come to affirm ourselves and the world in its transience, without going astray in our faith. This is what Johann Peter Hebel did in his Alemannic Apocalypse. Even if we are only dust in eternity: Faith, love, hope remain with us always. They are our best part. Especially as mortals, we may praise the beauty of the world – both this world and the world beyond – in full voice.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).