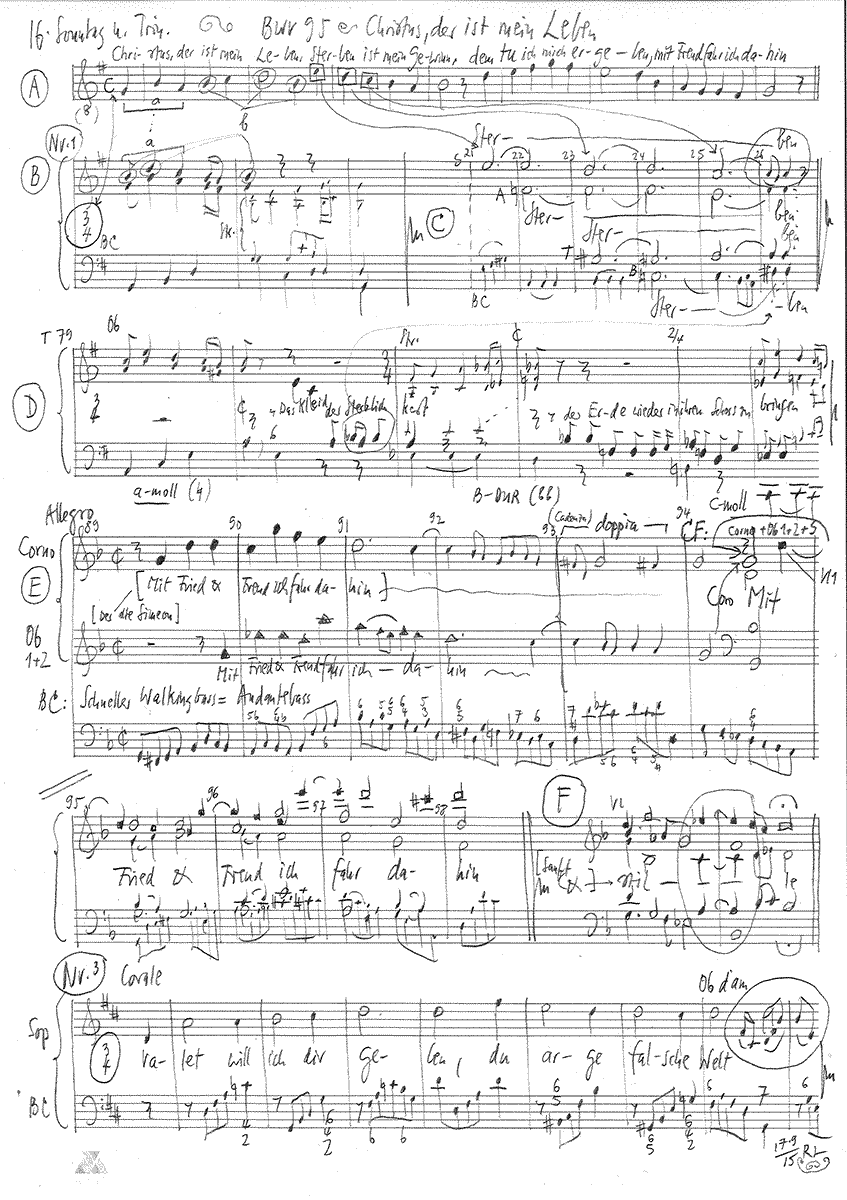

Christus, der ist mein Leben

BWV 095 // For the Sixteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Lord Christ, he is my being) for soprano, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, corno, oboe d’amore I+II, strings and basso continuo

First performed on 12 September 1723, the cantata “Lord Christ, he is my being” can be viewed as an experimental predecessor to Bach’s chorale cantata cycle of 1724/25. In contrast to the cantatas of the cycle, each of which interprets one single hymn, the libretto of BWV 95 incorporates no fewer than four different chorales; this lends the work a funereal quality, despite its relationship to the gospel for the 16th Sunday after Trinity, in which Jesus resurrects a widow’s son at Nain. And although the cantata is quite modest in terms of orchestration and scope, it brims with delightful ideas and innovative solutions.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Seitter, Olivia Fündeling, Guro Hjemli, Alexa Vogel, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Simone Schwark

Alto

Simon Savoy, Antonia Frey, Alexandra Rawohl, Misa Lamdark, Damaris Rickhaus

Tenor

Sören Richter, Walter Siegel, Nicolas Savoy, Manuel Gerber, Clemens Flämig

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, Will Wood, Valentin Parli, Oliver Rudin

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen, Sonoko Asabuki, Christine Baumann, Elisabeth Kohler, Eva Saladin

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone, Germán EcheverrI

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Katharina Arfken, Dominik Melicharek

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Corno

Olivier Picon

Lute

Maria Ferré

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Gian Domenico Borasio

Recording & editing

Recording date

18/09/2015

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Poet unknown, Jena 1609 (Melchior Vulpius?),

Poet unknown, Martin Luther 1524

Text No. 2, 4, 5, 6

Poet unknown

Text No. 3

Valerius Herberger, 1614

Text No. 3

Nikolaus Herman, 1560

First performance

Twenty-second Sunday after Trinity,

5 November 1724

In-depth analysis

The introductory chorus opens with a lively, syncopated ritornello, which – for a hymn of death – is set in a remarkably upbeat triple metre and features a lively dialogue between the strings and woodwinds on the one hand, and block-like choral interjections on the other. The tenor solo “With gladness, Yea, with joyful heart” then comes as a surprise, presenting an alternating series of arioso passages and recitative statements before cumulating in the second chorale “With peace and joy do I depart”. Through the energetic, driving bass line and signal-like motive based on the opening line of the chorale, this tutti section has a more decisive air than the first chorale of the movement, although both chorale settings have in common the use of dramatic rallentandi and fermata chords on the key words of “death” (chorale 1) and “calm and quiet” sleep (chorale 2).

Following this serene depiction of the afterlife, the soprano recitative embarks on a reckoning with the world and sin, which, with references to “Babel’s waters”, “Sodom’s apples” and the “passion’s salt”, is replete with moral imagery. Once again, refuge is eventually found by the vocalist in a chorale. The solo voice in this simple setting is first accompanied only by an ostinato-style continuo motive; when the tender oboes d’amore enter and fill this austere structure with a unifying cantilena, the relationship between humble prayer and the comfort of being heard is conveyed in a wordless language. Through the alternation between chorale and recitative sections, the first two movements alone comprise a five-part form.

The tenor recitative “Ah, if it could for me now quickly come to pass” then expresses a death wish that nonetheless does not end in a rejection of the world, but instead, throughout the following aria, relates a death scene, in which the striking of the last hour is portrayed as the door to idyllic pastures. The use of swaying oboe lines over pizzicato strings (without organ accompaniment) was a logical choice for the text; it also represents the type of setting standard in both sacred and operatic baroque music that Bach succeeds in lending an individual quality – even in the middle section of the movement, which retained the accompanying motive, despite intensifying the mood.

In the bass recitative, death is pronounced with sermon-like authority as the coveted sleep that lays the body to well-earned rest. The setting proffers a range of metaphors on homecoming and the good shepherd, ere the arioso conclusion melds into a closing chorale, “Since thou from death arisen art”, that underscores the import of Christ’s resurrection through the medium of congregational singing. In this movement, the vocal parts are overarched by a violin obbligato that perseveres through all dissonant harmonies – and thus symbolically through all life and death. After fear of death is vanquished in the fourth line of the verse, the violin part is free to soar heavenward – where Jesus Christ already thrones – and, like the dove of the New Covenant, to bear witness to Christ’s beatitude.

Libretto

1. Choral und Rezitativ (Tenor)

Christus, der ist mein Leben,

Sterben ist mein Gewinn;

dem tu ich mich ergeben,

mit Freud fahr ich dahin.

Mit Freuden, ja, mit Herzenslust

will ich von hinnen scheiden.

Und hieß es heute noch: Du mußt!

so bin ich willig und bereit,

den armen Leib, die abgezehrten Glieder,

das Kleid der Sterblichkeit

der Erde wieder

in ihren Schoß zu bringen.

Mein Sterbelied ist schon gemacht;

ach, dürft ichs heute singen!

Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin

nach Gottes Willen,

getrost ist mir mein Herz und Sinn,

sanft und stille.

Was Gott mir verheißen hat:

Der Tod ist mein Schlaf worden.

2. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Nun, falsche Welt!

nun hab ich weiter nichts mit dir zu tun;

mein Haus ist schon bestellt,

ich kann weit sanfter ruhn,

als da ich sonst bei dir,

an deines Babels Flüssen,

das Wollustsalz verschlucken müssen,

wenn ich an deinem Lustrevier

nur Sodomsäpfel konnte brechen.

Nein, nein! nun kann ich mit gelaßnerm Mute sprechen:

3. Choral

Valet will ich dir geben,

du arge, falsche Welt,

dein sündlich böses Leben

durchaus mir nicht gefällt.

Im Himmel ist gut wohnen,

hinauf steht mein Begier.

Da wird Gott ewig lohnen dem,

der ihm dient allhier.

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Ach könnte mir doch bald so wohl geschehn,

daß ich den Tod,

das Ende aller Not,

in meinen Gliedern könnte sehn,

ich wollte ihn zu meinem Leibgedinge wählen

und alle Stunden nach ihm zählen.

5. Arie (Tenor)

Ach, schlage doch bald, selge Stunde,

schlage doch bald den allerletzten Glockenschlag!

Komm, komm, ich reiche dir die Hände,

komm, mache meiner Not ein Ende,

du längst erseufzter Sterbenstag!

6. Rezitativ (Bass)

Denn ich weiß dies

und glaub es ganz gewiß,

daß ich aus meinem Grabe ganz einen sichern Zugang

zu dem Vater habe.

Mein Tod ist nur ein Schlaf,

dadurch der Leib, der hier von Sorgen abgenommen,

zur Ruhe kommen.

Sucht nun ein Hirte sein verlornes Schaf,

wie sollte Jesus mich nicht wieder finden,

da er mein Haupt und ich sein Gliedmaß bin!

So kann ich nun mit frohen Sinnen

mein selig Auferstehn auf meinen Heiland gründen.

7. Choral

Weil du vom Tod erstanden bist,

werd ich im Grab nicht bleiben;

dein letztes Wort mein Auffahrt ist,

Todsfurcht kannst du vertreiben.

Denn wo du bist, da komm ich hin,

daß ich stets bei dir leb und bin;

drum fahr ich hin mit Freuden.

Gian Domenico Borasio

“Bach and the ars moriendi”

In their acceptance of death during their lifetime as a natural and religious phenomenon, the way of life of people in Bach’s time differs quite significantly from ours. The cantata BWV 95 “Christus, der ist mein Leben” not only makes this abundantly clear, but also reveals the divine quid pro quo. Thus the cantata turns into an advertising event for the Protestant joy of eternity.

“Death is great.

We are His laughing mouth.

If we mean ourselves in the midst of life,

He dares to weep in our midst.”

Hardly any poet of German tongue has dealt with death as intensely and at the same time as sensitively and almost tenderly as Rainer Maria Rilke. For Rilke, death was a constant companion; a kind of red thread that runs through his entire oeuvre

- which did not prevent him from writing cheerful, exuberant verses full of the joys of life.

- perhaps that is precisely why he succeeded. Talking about the end of life

- or singing about the end of life is by no means something exclusively gloomy or paralysing. The Tibetan master Sogyal Rinpoche (author of the Tibetan Book of Living and Dying) once said:”If you are afraid of dying, I have good news for you – I can guarantee you that you will all die successfully”: I can guarantee that you will all die successfully). Indeed: none of us, if asked, would seriously doubt our own mortality. Would we? And yet, demonstrably, we very often behave as if we didn’t know about it, or perhaps didn’t want to know about it.

This is what fundamentally distinguishes our epoch from the 18th century, the age of J. S. Bach’s influence. In that time, death was omnipresent. There was no medical care worth mentioning, the average life expectancy was just 35 years (Bach himself lived to be 65, a very old man by the standards of the time). Illnesses, even banal infections, killed people without warning – even well-off ones. The famous Jean-Baptiste Lully, court musician at Versailles for the Sun King Louis XIV, died in 1687 of a banal infection he caught when he hit his big toe with a stick he was stamping on the floor to strike a beat.Dealing with death was part of everyday life in Bach’s day. That has changed only recently. Until a few years ago, the dead were laid out openly in Europe; in the countryside, everyone in the village came by and said goodbye, even the children. Today, people can grow very old without ever having seen a dead person, except in a TV thriller. Is this really conducive to a healthy approach to our mortality?

The Protestant response to people’s fears of death was to portray the earth as a vale of tears and death as the ultimate salvation from it. This becomes abundantly clear in this cantata “Christus, der ist mein Leben”, the lyrics almost hard to bear for today’s ears in places. The fact that Bach’s music is very credible in its portrayal of the joyful anticipation of death is made clear by another small detail: the chorale “Valet will ich Dir geben” uses a melody that is well known in Germany from church services – namely from the hymn “Den Herren will ich loben”. This song is based on the German text of the “Magnificat”, one of the most impressive hymns of praise in Holy Scripture. The lyrics date back to the 1950s. The melody, by the way, is not by Bach, who was a gifted recycler, but by Melchior Teschner from 1613. And one must admit that Teschner’s melody fits both texts very well.

Praise and farewell, joy and sorrow, life and death: not opposites in Bach’s time, but different but complementary aspects of human life. The so-called “ars moriendi”, the art of dying, was something prescribed from outside – namely by the church – into which one had to fit. Eternal joys beckoned as a reward, and the marketing for this was carried out – there was no television – by means of church music. Bach can therefore justifiably be called one of the most successful advertising musicians in history. Incidentally, he was also the inventor of secular advertising music, through the famous Coffee Cantata. Those were different times.

Today – across the board – one’s own mortality is suppressed. Instead, there is a lot of talk about self-determination, which seems to be the modern form of the “ars moriendi”. That sounds good too: self-determined dying. But what does that mean? In public, the discussion about this is shortened like a tunnel vision to self-determination of the time of death, keyword EXIT. But at the end of life, less than 1% of people actually make use of this option. So what is really important to people at the end of life? The scientifically proven answer is astounding: other people. All the palliative patients we examined in a study had predominantly altruistic values, in stark contrast to the healthy general population. What really counts at the end of life is very often not one’s own well-being. Here is a true story:

At 91, the old lady still had thick black hair (undyed, she pointed out) framing her narrow face, furrowed by deep wrinkles and always smiling somewhat sadly. She was suffering from ovarian cancer in an advanced stage, with metastases all over her body. Her life expectancy was only days to a few weeks.

When we were called in for counselling, the first thing we noticed was a multi-digit number tattooed on her left forearm. Mrs. K. was Jewish and had survived Auschwitz, the only one in her family to do so. She had emigrated to Israel after the war, but later returned to Germany. She held no grudges, but politely but firmly refused to talk about her life story.

When we reviewed her medical records, we were surprised that, given her very short life expectancy and poor general condition, she was still scheduled for a strong course of chemotherapy. We were even more surprised that it was explicitly ordered to resuscitate Mrs. K. in case of an acute deterioration – in view of her situation a hopeless undertaking and the opposite of what most people understand by a peaceful death. The doctors on the ward asked us to talk to the patient’s son, because he would make all the decisions. The son, born in Israel and still living there, was an Orthodox Jew. He explained to us politely but firmly that his faith made it imperative to exhaust all medical possibilities for prolonging life to the end, and that his mother would of course agree. Discussion was pointless.

When we managed to talk to the patient alone the next day, she smiled at us and said: “I know that I will die soon. I also know that all these treatments won’t do me any good except for side effects. But my son would not be able to cope if, after my death, he had the impression that he had not demanded and pushed through all the possibilities for prolonging my life. Then in God’s name let it be so.” Mrs K died a few days later under what was expected to be a futile attempt at resuscitation. She had achieved her goal.

Basically – and we experience this every day in palliative care: Every person dies differently, and most people die the way they lived. Two things can be concluded from this, namely firstly: that no institution, association, church or medical discipline can claim a monopoly on the definition of dying with dignity. What dignity means in each individual case can only be told to us by the person concerned himself. And secondly – as all great spiritual teachers tell us: preparation for death is the best preparation for life – and vice versa.

In conclusion, I would therefore like to talk about the role of spiritual care, spiritual accompaniment at the end of life. We have conducted a study on this: When a patient is asked in the clinic “Would you like to talk to the chaplain?” the most frequent answer is “Is it already that far with me?” But when we – as doctors! – ask patients “Would you describe yourself as a person of faith in the broadest sense of the word?” the answer is “Yes” in 87% of cases – and that in our largely secularised society. Pastoral care at the end of life is not only the task of the chaplains, but of the whole team. The patient chooses for himself who he wants to be accompanied by. This can be the nurse, the psychologist, the volunteer, or even the doctor. And sometimes the role boundaries are not quite sharply defined, as the following little story shows:

Mrs. W., an 87-year-old patient with terminal breast cancer whom I was asked to see for agitation, was a charming, petite old lady with no acute physical complaints. When I asked her about her fears, she told me that she was terrified of dying and what could possibly come afterwards. Within an hour she then told me her entire life and I listened without interrupting her monologue. After that she was a little calmer and we said goodbye. Of course, I was wearing the white coat with the name on it, the stethoscope etc. during the visit. But when the chaplain responsible for the ward made his rounds in the afternoon, she greeted him with the words: “You don’t need to come here, the priest was already here.

This is an anecdote that makes one smile. At second glance, however, the question arises as to what this says about our health care system when a doctor who does nothing but listen has to be unconsciously transferred to another profession by a mentally completely lucid patient because this behaviour obviously cannot be reconciled with her concept of a doctor. This has to change. It is my firm conviction: The medicine of the future will be a hearing one, or it will no longer be.

What is to be wished for all of us is a sober and serene view of our own finitude. This requires calm and repeated reflection, first on ourselves, and then preferably in conversation with those closest to us. Unfortunately, this happens rather rarely in life, and when it does, it is often very late. Let us take the time for it here and now. The heavenly music of Bach offers us an incomparable spiritual space for this. And precisely this reflection is perhaps the most important prerequisite for achieving that goal which – again – Rainer Maria Rilke formulated so incomparably:

“O Lord, give to each his own death.

The dying that goes out of that life,

in which he had love, meaning and need.”

Note

The text is partly based on passages from the author’s books “Über das Sterben” and “Selbst bestimmt sterben” (both published by C.H. Beck Verlag, Munich).

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).