In allen meinen Taten

BWV 097 // Unspecified occasion

(In all my undertakings) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo

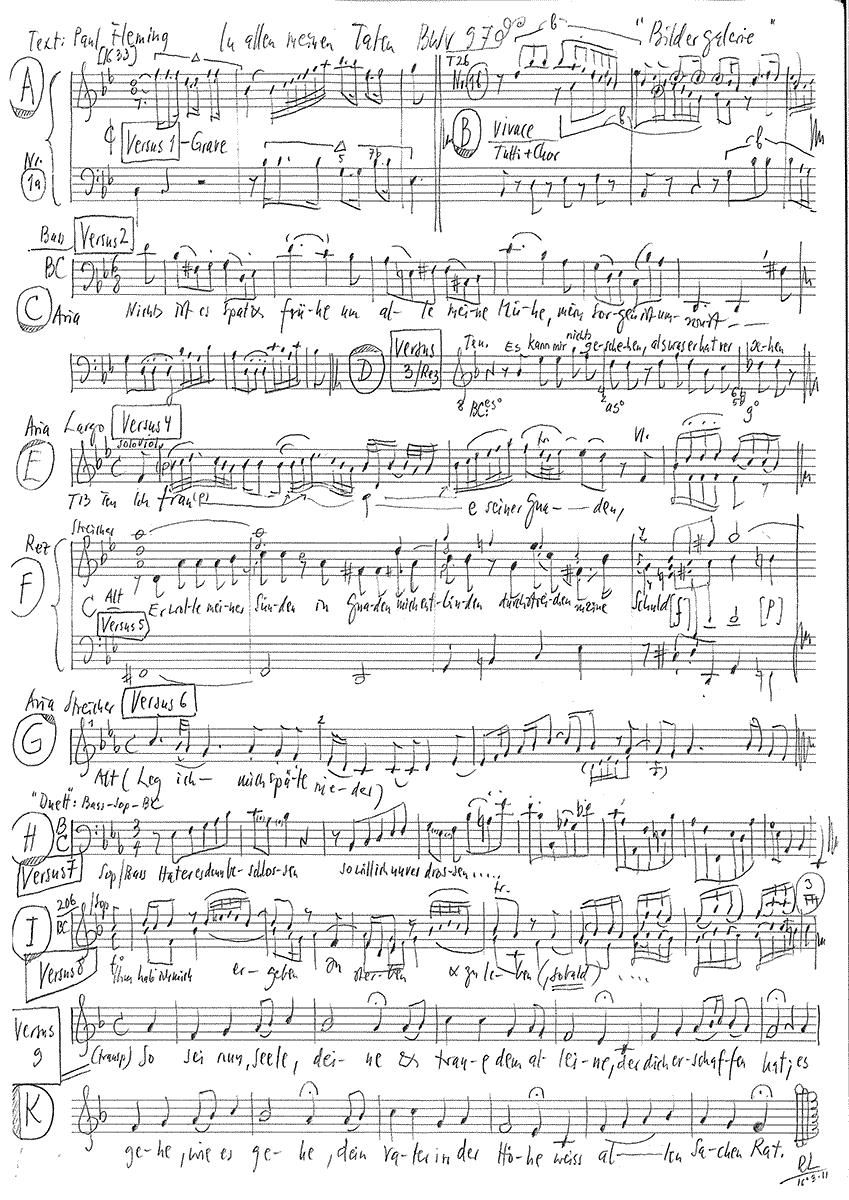

The cantata “In allen meinen Taten” (In all my undertakings) is set to a hymn by the brilliant baroque poet Paul Fleming (1609–1640), whose all-too-short life led him from Hartenstein in the Ore Mountains to Leipzig, Russia and Persia, then on to Hamburg and the Duchy of Holstein. With an autograph date of 1734, the cantata belongs to a group of four festive sacred works with no specific connection to the church year and that are based entirely on the chorale verse “Per omnes versus”. Accordingly, the individual movements are not described as recitatives or arias, but as “Versus 1” to “Versus ultimus”; the cantata’s internal structure, however, is determined considerably by the strophic form of each verse as two three-line “Stollen”. In recent years, Bach scholar Marc-Roderich Pfau has posited that this group of works may have been written for the Court of Weissenfels. Indeed, Bach had been appointed titular Kapellmeister of the court in 1729, although it is not known whether he provided any musical services. Notes in the source text moreover suggest that the work was later reused as wedding music.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Leonie Gloor, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Damaris Nussbaumer

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Simon Savoy, Francisca Näf

Tenor

Walter Siegel, Nicolas Savoy, Manuel Gerber

Bass

Manuel Walser, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Fanny Tschanz, Christine Baumann, Sylvia Gmür, Martin Korrodi, Olivia Schenkel

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Diego Nadra

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Kerstin Odendahl

Recording & editing

Recording date

03/18/2011

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Paul Fleming, 1633

Year of composition

1734

In-depth analysis

The introductory chorus is set as a twopart orchestral overture in whose fugal vivace section the soprano cantus firmus, accompanied by lively pre-imitations, is embedded. The extended trio episode for oboes and continuo calls to mind an original, purely orchestral setting; after the full rendition of the chorale, however, Bach included an arioso coda set for all four voices over the last line of the hymn, thus enhancing the light and elegant tone of the movement.

The second hymn verse, by contrast, is set as a duo for bass vocalist and continuo, and the latter’s gigue-like part could easily be mistaken for a movement from the Bach Cello Suites, were it not for the soothing cantabile effect of the chanson-like vocal line. Despite its straight-forward sequences, the movement is highly distinctive by virtue of its learned and – as typical of Bach – complex passages. In the following tenor recitative, the hymn text is treated as a prose text without melodic import, which lends the brief movement the character of an oddly laconic transition.

In the aria for tenor, violin solo and continuo, by contrast, Bach presents music of almost boundless artistry, which, despite the subtle interpretation of certain words, can hardly have been inspired by the placid verse “I trust in his dear mercy”. Over a peaceful bass line, the solo violin part, replete with multiple stops, broken chords and wild cascades, is of such demonstrative virtuosity that it appears Bach must have written it as a showpiece for a particular violinist – a practice seen in the works of other baroque masters, for instance, the sacred compositions of Antonio Vivaldi. Whatever the exact circumstances, it is possible to make a speculative connection to a particular passage in Psalm 119, “Thy statutes have been my songs in the house of my pilgrimage”. These words, chosen by Heinrich Schutz, grand seigneur of German music in Weissenfels, as his gravestone inscription tally with Bach’s personal conviction that artistry, indeed, can attest the practicing musician’s vindication through faith.

The alto recitative, again not distinctly melodic, gains emotional depth through the string accompagnato, which lends considerable solemnity to the otherwise straightforward confession of sin and subsequent judgement. This gives way in verse six to a setting, at once quaint and modern, whose dance-like elements are balanced by the compact, syncopated string writing and the sensitive rendering of key words such as “retiring” and “in weakness and in bondage”, while the industrious string lines echo the Protestant activity alluded to in the verse.

The soprano and tenor duet features capricious lines and a whimsical, fleeting tone that make it reminiscent of a secular chamber- music cantata. With its wilful succession of entries and some over-long solo lines, the setting gives the impression of a not entirely successful compromise between the threepart da-capo form of the music and the twopart structure of the hymn verse. The penultimate verse then strikes a different tone, employing the warm timbre of the oboes over an accompanying bass line. Like an opera aria of the Middle German baroque, the setting combines profound sensitivity with motivic efficiency; in combination with the simple soprano melody, this engenders an enchanting resonance reminiscent of the “sonate a quattro” of Telemann and Zelenka.

The closing verse, once again for the tutti ensemble, reflects the concise unity of the text in a four-part vocal setting with arioso interludes. Supplemented by no less than three independent string parts, the movement exudes a sparkling, celebratory character. As such, it forms a fitting conclusion to a composition that, in tone as well as in numerous details, reflects Bach’s new orientation towards greater cogency and cantabile quality – an approach that contemporaries such as Johann Abraham Birnbaum had already detected in Bach’s few cantata compositions of the 1730s.

Libretto

1. Chor

In allen meinen Taten

laß ich den Höchsten raten,

der alles kann und hat,

er muß zu allen Dingen,

solls anders wohl gelingen,

selbst geben Rat und Tat.

2. Arie (Bass)

Nichts ist es spat und frühe

um alle meine Mühe,

mein Sorgen ist umsonst.

Er mags mit meinen Sachen

nach seinem Willen machen,

ich stells in seine Gunst.

3. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Es kann mir nichts geschehen,

als was er hat versehen

und was mir selig ist;

Ich nehm es, wie ers gibet;

was ihm von mir beliebet,

das hab ich auch erkiest.

4. Arie (Tenor)

Ich traue seiner Gnaden,

die mich vor allem Schaden,

vor allem Übel schützt.

Leb ich nach seinen Gesetzen,

so wird mich nichts verletzen

nichts wird mich verletzen,

nichts wird mir fehlen,

nichts fehlen, was mir nützt.

5. Rezitativ (Alt)

Er wolle meiner Sünden

in Gnaden mich entbinden,

durchstreichen meine Schuld!

Er wird auf mein Verbrechen

nicht stracks das Urteil sprechen

und haben noch Geduld.

6. Arie (Alt)

Leg ich mich späte nieder,

erwache frühe wieder,

lieg oder ziehe fort,

in Schwachheit und in Banden,

und was mir stößt zuhanden,

so tröstet mich sein Wort.

7. Arie (Duett Sopran, Bass)

Hat er es denn beschlossen,

so will ich unverdrossen

an mein Verhängnis gehn!

Kein Unfall unter allen

wird mir zu harte fallen,

ich will ihn überstehn.

8. Arie (Sopran)

Ihm hab ich mich ergeben

zu sterben und zu leben,

sobald er mir gebeut.

Es sei heut oder morgen,

dafür laß ich ihn sorgen;

er weiß die rechte Zeit.

Kerstin Odendahl

“Trust in God as a Power for Change”

The uprising in the Arab world in the mirror of the Bach cantata “In all my deeds”.

Departure

the day before yesterday i returned from a two-week stay in abu dhabi. i was there as a visiting professor. in my hand luggage i had, among other things, the text of the bach cantata “in allen meinen Taten” (in all my deeds). i found the reading fitting: a poem written by paul fleming before setting off on a journey of several years to persia accompanied me on a journey to the persian gulf.

Paul Fleming was an important German baroque poet. Born in 1609 in Hartenstein, Saxony, he studied philosophy and medicine in Leipzig, while devoting himself to poetry. In 1633, through the intercession of a friend, he became part of a legation of Duke Friedrich III of Holstein-Gottorp to Persia. The journey lasted a total of six years. Paul Fleming’s poem, which was to become a well-known travel song, was apparently written before his departure. Bach later included most of the verses in his cantata.

From journey to life’s journey

The cantata begins as a song of confidence before setting off into the unknown:

“In all my deeds

I leave it to the Most High to advise me,

who can and has all things, (…)”

It testifies to the feeling of being protected:

“Nothing can happen to me

but what he has provided,

and what is blessed to me, (…)”.

And it reflects the deepest trust in God:

“I trust in his graces,

which protects me from all harm,

from all evil.”

After a few stanzas, however, the travel song turns into an examination of man’s “journey through life”. It is about strokes of fate:

“If then he has decreed it,

I will go undaunted

to my doom!”

And it is about death:

“To him I have surrendered

To die and to live

as soon as he shall give me leave.”

At the end, however, there is again – as at the beginning of the journey or life journey – trust in God, the Almighty:

“(…) let it be as it may,

Your Father on high

knows counsel in all things.”

Doubts

Shortly before I started my journey, the people of many Arab states had begun to rise up against the oppressive regime. People were demanding the resignation of corrupt and dictatorial rulers, demanding life chances, justice, the preservation and promotion of their rights, especially those to dignity, equality, freedom of expression and political participation. My lecture in Abu Dhabi was on human rights (of all things!).

I explained to my students that human rights are no longer a purely national issue. They were an international task and obligation. Under current international law, essential human rights bind all states and their governments. Around us, however, numerous Arab rulers responded to the demands of their people with repression, even massive armed violence. Libyan dictator Ghadhafi massacred his own people.

“I trust in his grace,

who protects me from all harm,

from all evil.”

I explained to my students that the guarantee of human rights under international law today was linked to international sanctions and enforcement mechanisms. These could be enforced by peaceful means, but in extreme situations also by military means. The latter is the task of the United Nations Security Council. The Security Council, however, hesitated in the case of Libya. Its members disagreed on whether the international community should intervene or not. Instead of enforcing human rights, the most powerful institution under international law simply looked on.

“Nothing can happen to me

but what he has provided,

and what is blessed to me, (…)”

Towards the end of my stay, the uprising in Bahrain intensified. On my last day of lectures, the Bahraini king called in Saudi troops as well as Emirati police forces and declared a state of emergency. The aim was to use force to quell the demonstrators’ demands for democracy and equality, at the cost of more civilian deaths.

“If he has decreed it,

“then I will be undaunted,

to my doom!”

As a lawyer of international law, I was in despair. What is international law good for, what are international human rights guarantees good for, if they are trampled underfoot? What use are treaties and rules if the enforcement mechanisms are weak? And what legitimacy can the only truly powerful body, the United Nations Security Council, claim if it is blocked due to political considerations? And finally: What am I actually doing in Abu Dhabi? My students consisted to a not inconsiderable extent of members of the powerful families from the Gulf region. Did they actually understand what I was trying to convey to them? That as rulers they have a duty to treat people with dignity, to grant them equality and opportunities in life?

“(…) I take it as he gives it,

what he pleases of me,

that I have also chosen.”

Did Paul Fleming have any idea at all of the cruelties, of the blows of fate in life? In view of the realities, the brutality of man, how can one accept everything as God-given, trust in God, when we see that in large parts we have not heaven but hell on earth? Were people in the 17th century so godly that they let everything happen to them?

If so, the Bach cantata would be completely outdated today.

Hope and courage

However, the reality of Paul Fleming’s life stands in the way of such an interpretation. He wrote the travel song in the midst of the turmoil of the Thirty Years’ War, probably the greatest man-made catastrophe. The war and its effects also left their mark on him. And setting off with a legation to Persia was then a journey with far greater dangers than we can imagine today. Perhaps Paul Fleming was simply a brave man?

The insurgents in the Arab world are mostly young men and women fighting for a dignified life and for better government. They are prepared to die for their rights. They often invoke Allah, who gives them the strength to rise up. i don’t think the demonstrators know the 1981 “Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights” or the 1990 “Cairo Declaration of Human Rights in Islam”. These two religious – not international law – documents declare that the granting of human rights is part of Islam. i quote the first paragraph of the “Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights”: “Islam gave mankind an ideal code of human rights fourteen centuries ago. These human rights aim to grant honour and dignity to humanity and to abolish exploitation, oppression and injustice.” In Islam, God created human rights. Accordingly, the protesters draw their strength, probably without knowing it, from the right source. So they do:

“(…) and whatever comes to my hand,

his word comforts me.”

As Ghadhafi’s use of force grew in scale, the Arab League denied him any legitimacy and called on the Security Council, on behalf of the Arab world, to establish a no-fly zone over Libya so that at least the bombing of the population would stop. Last night, the Security Council adopted this no-fly zone.

In doing so, it even went beyond the original demand and authorised states to protect Libya’s population from the air by military means if necessary. The first states, including the Arab state of Qatar, have declared their willingness to participate in the measures. This afternoon, Libya announced an immediate ceasefire. Although the situation remains unclear and the Libyan despot’s dodges are not to be trusted: the protection mechanisms under international law have – finally – started to work. So it is:

“Nothing is it late and early

for all my trouble

my worries are in vain.”

Among my students were also young people from Bahrain. On the last day of the lecture, immediately after a state of emergency was declared in Bahrain and massive action was taken against the demonstrators, we discussed – of all things – the “Arab Charter on Human Rights”, an international treaty from 2004. According to Articles 24 and 30, every citizen has, among other things, the right to engage in political activity, the right to vote or be elected, the right to equal access to public office, and freedom of expression and assembly. Spontaneously, a student from Bahrain exclaimed, “But we didn’t sign that!” I replied, “Yes, we did. Please look at the list of States Parties. Bahrain signed the Charter in 2005 and ratified it in 2006.” “I wasn’t serious,” was the laughing but somewhat pained and uncertain reply. “In international law, everything is serious,” I countered. “The state that signs and ratifies a treaty is bound by it. A signature is valid. Bahrain is committed to upholding those human rights.” The silence that followed probably lasted only a few seconds; by the feel of it, however, it stretched on for minutes. At the end of the lecture, the students thanked me, some effusively, for the ten-day lecture – including my Bahraini student. So maybe my efforts were not in vain after all?

“In all my deeds

I let the Most High advise me,

who can and has all things (…)”

Paul Fleming was not a naïve man resigned to fate, but a courageous man who took his strength to set out from faith and trust in God. He understood human existence as a journey to be lived. The experiences during my journey to the Arab world showed me that we still think this way today. We sometimes despair, we don’t understand, all is not well for a long time. Nevertheless, trust in God can give us the strength, the freedom to live – in all religions that believe in God.

Arrival

On the flight back to Europe, I switched on the in-flight music programme. I admit that in my free time I listen not only to Bach cantatas, but also frequently and with pleasure to pop music. While “zapping” (as they say nowadays), I came across the song “Universum” by the German pop group “ich & ich” from their album “Gute Reise”, which I had not heard before. i was overwhelmed. It was as if I was listening to the Bach cantata, only with a different melody and different lyrics:

“You can fly to the mountains

through Mongolia

dive into the deepest depths

feel free!

The universe expands.

You can climb the peaks

swim to all the islands.

In your heart I am there anyway,

because I am always your home.

You can fly to the stars,

past Orion,

dive in the Mariana Trench,

Feel free!

The universe is expanding.

You can climb Mount Everest

Swim all the way to Iceland.

In your heart I’m there anyway,

because I’m always your home.

– I am always your home’.”

God is not always understandable to us. But he gives us the power – the power to live and the power to change. We are free.

Literature

– Jörg-Ulrich Fechner, Paul Fleming, in: Harald Steinhagen/Benno von Wiese (eds.), Deutsche Dichter des 17. Jahrhunderts. Their Lives and Works, Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 1984, pp. 365-384.

– Rudolf Alexander Schröder, Paul Fleming. Ein Blick auf sein Leben und seine Werke, in: Vorstand der Bremer Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft (ed.), Abhandlungen und Vorträge, Jahrgang 5 (1931), Gustav Winter’s Buchhandlung Franz Quelle Nachf. Bremen, pp. 154-200.

– Hans-Joachim Schulze, The Bach Cantatas. Introduction to all of Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantatas, Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2006, pp. 565-568

– Press reports from the period 1 to 18 March 2011

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).