Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan

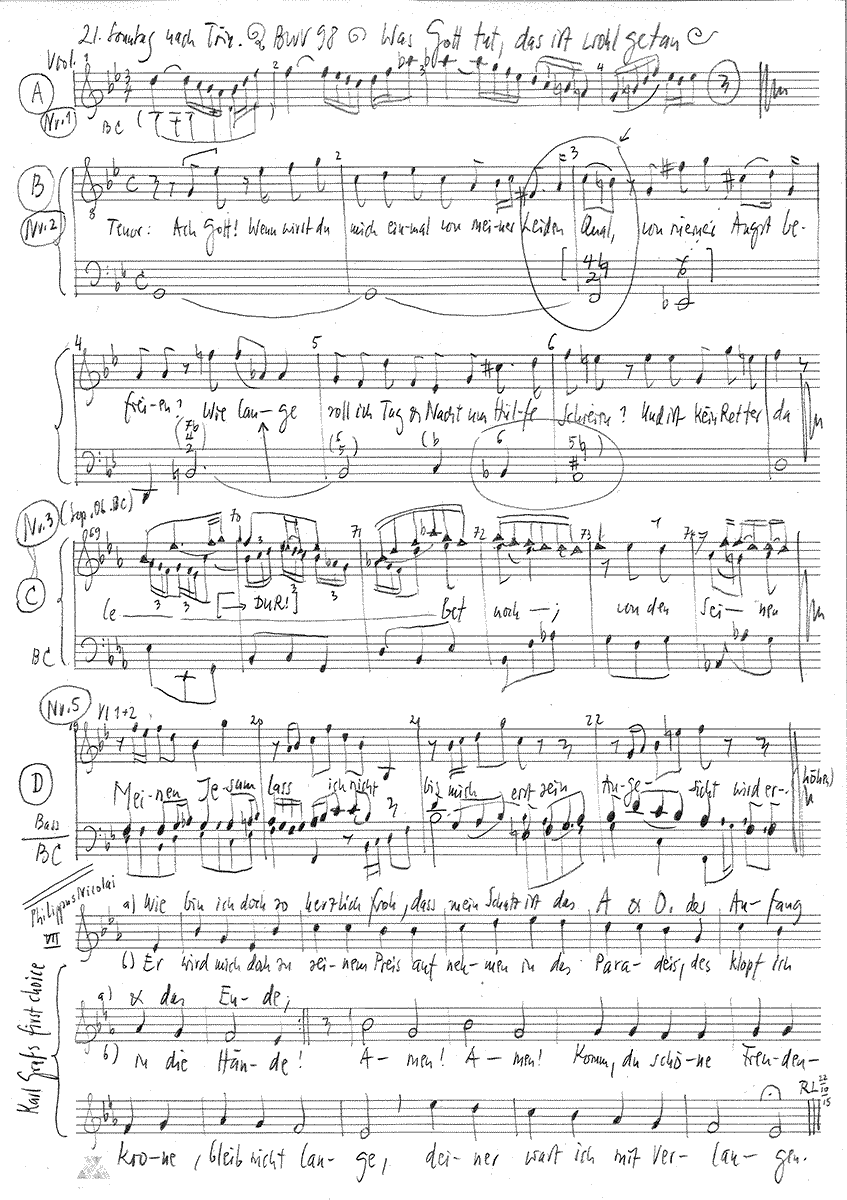

BWV 098 // For the Twenty-first Sunday after Trinity

(What God doth, that is rightly done) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, taille d’hautbois, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Herr, lehre doch mich, dass es ein Ende mit mir haben muss und mein Leben ein Ziel hat und ich davon muss. Siehe, meine Tage sind einer Hand breit bei dir, und mein Leben ist wie nichts vor dir. Wie gar nichts sind alle Menschen, die doch so sicher leben! Sie gehen daher wie ein Schemen und machen sich viel vergebliche Unruhe; sie sammeln und wissen nicht, wer es einnehmen wird. Nun, Herr, wes soll ich mich trösten? Ich hoffe auf dich.

Zuletzt, meine Brüder, seid stark in dem Herrn und in der Macht seiner Stärke. Ziehet an den Harnisch Gottes, dass ihr bestehen könnet gegen die listigen Anläufe des Teufels. Denn wir haben nicht mit Fleisch und Blut zu kämpfen, sondern mit Fürsten und Gewaltigen, nämlich mit den Herren der Welt, die in der Finsternis dieser Welt herrschen, mit den bösen Geistern unter dem Himmel. Um deswillen ergreifet den Harnisch Gottes, auf dass ihr an dem bösen Tage Widerstand tun und alles wohl ausrichten und das Feld behalten möget. So stehet nun, umgürtet an euren Lenden mit Wahrheit und angezogen mit dem Panzer der Gerechtigkeit und an den Beinen gestiefelt, als fertig, zu treiben das Evangelium des Friedens. Vor allen Dingen aber ergreifet den Schild des Glaubens, mit welchem ihr auslöschen könnt alle feurigen Pfeile des Bösewichts; und nehmet den Helm des Heils und das Schwert des Geistes, welches ist das Wort Gottes.

Und es war ein Königischer, des Sohn lag krank zu Kapernaum. Dieser hörte, dass Jesus kam aus Judäa nach Galiläa, und ging hin zu ihm und bat ihn, dass er hinabkäme und hülfe seinem Sohn; denn er war todkrank. Und Jesus sprach zu ihm: «Wenn ihr nicht Zeichen und Wunder sehet, so glaubet ihr nicht.» Der Königische sprach zu ihm: «Herr, komm hinab, ehe denn mein Kind stirbt!» Jesus spricht zu ihm: «Gehe hin, dein Sohn lebt!» Der Mensch glaubte dem Wort, das Jesus zu ihm sagte, und ging hin. Und indem er hinabging, begegneten ihm seine Knechte, verkündigten ihm und sprachen: «Dein Kind lebt!» Da forschte er von ihnen die Stunde, in welcher es besser mit ihm geworden war. Und sie sprachen zu ihm: «Gestern um die siebente Stunde verliess ihn das Fieber.» Da merkte der Vater, dass es um die Stunde wäre, in welcher Jesus zu ihm gesagt hatte: «Dein Sohn lebt.» Und er glaubte mit seinem ganzen Hause. Das ist nun das andere Zeichen, das Jesus tat, da er aus Judäa nach Galiläa kam.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Seitter, Anna Walker, Mirjam Berli, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Simone Schwark, Lia Andres

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Lea Scherer, Liliana Lafranchi, Alexandra Rawohl

Tenor

Achim Glatz, Marcel Fässler, Sören Richter, Clemens Flämig

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky, William Wood, Daniel Pérez

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Sabine Hochstrasser, Yuko Ishikawa, Olivia Schenkel, Fanny Tschanz, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Martina Zimmermann

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Dominik Melicharek

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Tilmann Moser

Recording & editing

Recording date

23/10/2015

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Samuel Rodigast, 1674

Text No. 2–5

Poet unknown

First performance

Twenty-first Sunday after Trinity,

10 November 1726

Libretto

1. Choral

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

es bleibt gerecht sein Wille.

Wie er fängt meine Sachen an,

will ich ihm halten stille.

Er ist mein Gott,

der in der Not

mich wohl weiß zu erhalten;

drum laß ich ihn nur walten.

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Ach Gott! Wenn wirst du mich einmal

von meiner Leiden Qual,

von meiner Angst befreien?

Wie lange soll ich Tag und Nacht

um Hülfe schreien?

Und ist kein Retter da!

Der Herr ist denen allen nah,

die seiner Macht

und seiner Huld vertrauen.

Drum will ich meine Zuversicht

auf Gott alleine bauen,

denn er verläßt die Seinen nicht.

3. Arie (Sopran)

Hört, ihr Augen, auf zu weinen!

Trag ich doch

mit Geduld mein schweres Joch.

Gott der Vater, lebet noch;

von den Seinen

läßt er keinen.

Hört auf zu weinen!

Hört, ihr Augen, auf zu weinen!

4. Rezitativ (Alt)

Gott hat ein Herz, das des Erbarmens Überfluß.

Und wenn der Mund vor seinen Ohren klagt

und ihm des Kreuzes Schmerz

im Glauben und Vertrauen sagt,

so bricht in ihm das Herz,

daß er sich über uns erbarmen muß.

Er hält sein Wort;

er saget: Klopfet an,

so wird euch aufgetan.

Drum laßt uns alsofort,

wenn wir in höchsten Nöten schweben,

das Herz zu Gott allein erheben.

5. Arie (Bass)

Meinen Jesum laß ich nicht,

bis mich erst sein Angesicht

wird erhöhen oder segnen.

Er allein

soll mein Schutz in allem sein,

was mir Übels kann begegnen.

Tilmann Mose

“The thankful arrogance of the survivors”.

Contoverses on the cantata “Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan” (BWV 98): why it is so difficult to believe in God. Insight into an anti-theology.

My text about the text of the cantata will hopefully not come as a shock. It comes from the author of the book “God Poisoning”, a reckoning with my image of God, which has been published 100,000 times in paperback since the seventies. When I received the invitation to this reflection many months ago, I was delighted and immediately accepted. But when I received the text of the cantata weeks later, I was startled: it contains the very promises and petitions I trusted as a child and which then led me far away from God until the writing of my great indictment at the age of forty. It has become the textbook for ethics and religion in upper secondary school classes. It is an indictment with which I wanted to wrest myself from God’s grasp and rid myself of my disappointment. And the result made me satisfied: He has left me alone ever since, and I leave Him alone. He no longer seeks me out, tempting and reproaching from his side, and I am no longer filled with hatred and grim counter-complaints. We ignore each other. I no longer need to fear God and I no longer need to always thank him for my sinful existence and his seemingly necessary grace. I never reached out to him in prayer, and I no longer wanted to believe in his existence because it seemed absurd to me. So: no credo quia absurdum, as ancient theologians say.

The Christians who had narrowly survived war, plague, famine and expulsion through the centuries thanked God for his eternal justice with which he had saved them, while the millions who had perished had probably not been worthy of his salvation. A grateful pious elite in the Old Testament had survived and praised his very special grace, the rest he had probably sacrificed to his justice also sung about in the cantata “Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan”. The grateful arrogance of all the survivors was unbearable to me. The sentence “How could God allow this?”, which drives many people crazy in their faith, in relation to the atrocities of war and not least the Holocaust, also hit me with full force. I could no longer trust his higher power, especially not the first two lines of the cantata:

“What God does is well done,

His will be done.”

I can understand that people want to owe their survival to him, rescue from fear, famine and disease. Thanks for holding and keeping his hand over them in happiness and suffering. I can understand it as a prayer, but not as an assured promise, as the text so wonderfully set to music by Bach represents. As the Almighty, he has repeatedly destroyed humanity again, which was depraved for him, by flood, fire and sword, because they did not follow his arbitrary commandment of obedience.

He experimented very cruelly with the creation of mankind, which I do not consider at all successful and “well-done”, but rather an unusually unsuccessful botch-up as far as our species is concerned. A glance at a single newspaper is enough to make one despair about the creation of mankind. Even his first two humans thumbed their noses at him, and he immediately took revenge, out of anger and despair. He supposedly created us in his image, and that is bad enough after his irascible and cruel character in the Old Testament. More than that, he tortures and murders, to correct the almighty act of creation, his only son, because we keep failing in his gigantic experiment of obedience and therefore he supposedly has to sacrifice him in love for our sins. We had to be sinners in order to deserve his redemption, his mercy, his grace. This is also about original sin and its permanent consequences, which we owe to St Augustine.

This God craves thanks, and the churches have drilled thanks into us. I have never really understood what for. But Bach’s music is also wonderful thanksgiving, but a very different one, a beatific one, which a friend of mine once called “his sanatorium of the soul” for himself with shining eyes.

I had to anxiously call the organiser to ask how much of my own truth and anti-theology I was allowed to add to the Bach music that gripped us today. I feared a scandal at this pious event. But I should risk it, I received in reply, if the strictly individual autobiographical character of my doubts and anger became clear. I have become mild as a therapist for tormenting ecclesiogenic neuroses when people who have lived their lives under the question and hope come into distress of faith:

“How long shall I day and night

cry for help?

And is there no Saviour!”

Yet, Bach miraculously set the hope of the Saviour to music, and he may still have believed it:

“The Lord is near to all

who trust in his power (…).

Therefore I will build my confidence

in God alone,

for he forsaketh not them that are his.”

Bach’s music I can pray along with, but not his lyrics. Most singers and musicians in his ministry today – I have interviewed many – live with this split because they cannot bear the believing supplication in many of the texts if they only read them. If you let yourself be comforted and redeemed by Bach’s music today, you no longer have to be devout, even if Bach still was from the bottom of his heart. One may become pious with him without having a believing heart. Then our thanksgiving is genuine, but not the thanksgiving that the church and theology demand of us for the supposedly wonderful world from God’s hand. We are supposed to make this world more human, not more divine. But supposedly he called us before our birth and with our name.

My theology is: God was bored to the point of insanity in his infinite cosmos, the late spectacle of the animal world was no longer enough for him. He did not deliberately create humans, as the narrow-minded creationists believe, but rather let us emerge from the primates in a miserably long process. He then wooed us with incredibly tempting offers and at the same time threatened us with hell if we did not show submissive faith.

In the past, I would have ended the text with the request: “Readers, pray for me. Now it is enough for me if you do not condemn me. I thank you for enduring my text.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).