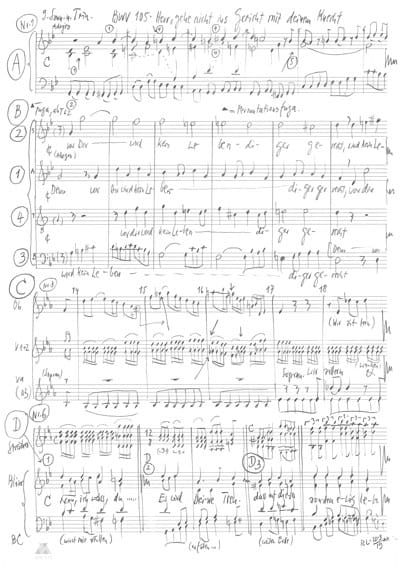

Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht

BWV 105 // For the Ninth Sunday after Trinity

(Lord, go thou not into court with this thy thrall) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, corno da tirarsi, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Olivia Fündeling, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Damaris Rickhaus, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Tobias Mäthger, Christian Rathgeber, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Grégoire May, Retus Pfister, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Markéta Knittlová, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sonoko Asabuki, Katya Polin

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Corno da tirarsi

Olivier Picon

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Christian M. Rutishauser

Recording & editing

Recording date

22/03/2019

Recording location

Trogen (AR) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler, Nikolaus Matthes

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

First performance

25 July 1723, Leipzig

Text

Psalm 143:2 (movement 1); Johann Rist (movement 6); anonymous (movements 2–5) [W. Murray Young presumes Christian Weiss, Sr.]

In-depth analysis

Cantata BWV 105, “Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht” (Lord, go thou not into court), was composed for the Ninth Sunday after Trinity in 1723. Because it numbers among the earliest publications of Bach’s works (around 1830/31), the composition was influential in shaping the perception of Bach in the romantic period – despite its technical difficulty as well as its, in many respects, unorthodox character.

Set in binary form, the introductory chorus features a three-section adagio prelude followed by a rapid, rigorously ordered fugue. Opening in the dense tonality of G minor, the music combines heavy repeated quavers in the continuo line with syncopated, intertwining suspended notes in the string and oboe parts that elicit a chain of griefstricken sighs. Against this backdrop of sorrow and despair, the unaccompanied choir then delivers a first plea for protection, which is lent a pressing urgency by the fearful whimpering and helpless separation of the vocal entries. In the following reiterations of this dictum (with the voices in different constellations), the intensity of the mood is further heightened by compositional nuances such as the addition of obbligato instrumental material and the shortening of the last interlude. Over an ominous pedal point, an impasse is reached in the hopeless, circling motives, ere a fugue emerges, whose mechanical and driven execution is somewhat reminiscent of the organ fugue in G Minor BWV 542, and in which the devastating message of “with thee there is no living person just” is revealed with tormenting inexorability. Indeed, there is hardly a musical setting that expresses with such harrowing intensity Luther’s doctrine of the impossibility for humans to attain mercy through their own deeds.

The alto recitative then transforms this devastating revelation into a subjective appeal for repentance. In light of the threatening presence of God as both witness and magistrate on the preordained day of judgement, the best recourse is outright admittance of the errors of one’s ways – an apt approach for the “blemished” sound, with its abundance of diminished intervallic leaps.

In the following soprano aria, Bach employs an extreme measure to demonstrate the consequences of such abysmal sin: by eschewing the standard baroque reliance on a continuo line, he creates a fragile structure of high-register viola figures and slow semiquaver tremolo in the violin parts, over which broad motivic sequences from the oboes and vocalist enter into an erratic and broken dialogue. In this musical depiction of inner turmoil, tenderness and lamentation make for a truly heartrending pairing.

Then arrives the turning point, and it could not be achieved more poignantly than in this delicate B-flat major setting. Accompanied by pizzicato basses and a confiding string figure, the sonorous bass recitative opens an unexpected door to the realm of solace. Here we encounter none other than Jesus himself, who through his sacrifice stands guarantor for us at the time of judgement, nailing humankind’s register of debt to the cross and redeeming it on our behalf. The inevitability of death, however, is in no way concealed in this setting: expressed as a thoroughly painful descent into sand and dust, it is nonetheless also the entrance to the eternal shelter of paradise.

The tenor aria, for its part, appears to follow dual intentions. While the energetic dancelike gesture supported by a robust horn line underscores the believer’s determination to go safely through life with Jesus, the shimmering demisemiquavers of the violin part illustrate the circling presence of Mammon, which the vocalist, for all his hesitant deceptive cadences, so ardently wishes to forsake. In this setting, the extremely difficult violin and horn parts substantially contribute to the profound struggle between a corrupt world and hard-fought distance from earthly temptations.

In the closing chorale, Bach once again abandons all convention. Through the addition of accompanying parts and interludes, the increasingly reassuring message of the text – traversing from the torments of conscience to a trusting vision of eternal life – is illustrated by a rhythmic deceleration in four steps from semiquaver tremolos, to straight triplets, to groups of quavers then swung triplets – a device that together with the questioning echo renders the text affect audibly palpable. Indeed, that the new Thomascantor had the will to interpret every little nuance of the chorale with the greatest artistic skill must have become eminently clear to the Leipzig congregation on that 25 July 1723.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht.

Denn vor dir wird kein Lebendiger gerecht.»

2. Rezitativ — Alt

Mein Gott, verwirf mich nicht,

indem ich mich in Demut vor dir beuge,

von deinem Angesicht.

Ich weiß, wie groß dein Zorn

und mein Verbrechen ist,

daß du zugleich ein schneller Zeuge

und ein gerechter Richter bist.

Ich lege dir ein frei Bekenntnis dar,

und stürze mich nicht in Gefahr,

die Fehler meiner Seelen

zu leugnen, zu verhehlen!

3. Arie — Sopran

Wie zittern und wanken

der Sünder Gedanken,

indem sie sich untereinander verklagen,

und wiederum sich zu entschuldigen wagen.

So wird ein geängstigt Gewissen

durch eigene Folter zerrißen.

4. Rezitativ — Bass

Wohl aber dem, der seinen Bürgen weiß,

der alle Schuld ersetzet,

so wird die Handschrift ausgetan,

wenn Jesus sie mit Blute netzet.

Er heftet sie ans Kreuze selber an,

er wird von deinen Gütern, Leib und Leben,

wenn deine Sterbestunde schlägt,

dem Vater selbst die Rechnung übergeben.

So mag man deinen Leib, den man zu Grabe trägt,

mit Sand und Staub beschütten,

dein Heiland öffnet dir die ewgen Hütten.

5. Arie — Tenor

Kann ich nur Jesum mir zum Freunde machen,

so gilt der Mammon nichts bei mir.

Ich finde kein Vergnügen hier

bei dieser eitlen Welt und irdischen Sachen.

6. Choral

Nun, ich weiß, du wirst mir stillen

mein Gewissen, das mich plagt.

Es wird deine Treu erfüllen,

was du selber hast gesagt:

daß auf dieser weiten Erden

keiner soll verloren werden,

sondern ewig leben soll,

wenn er nur ist Glaubens voll.

Cantata BWV 105: Reflection by P. Dr. Christian M. Rutishauser SJ

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen

It is a joy to listen to this cantata together. What richness of tone colours, voices and rhythms! Recitatives and arias push forward. A stringent sequence of thoughts corresponds to this musical ductus. A stage has opened up in me. There stands the worshipper before God the judge. The worshipper is as if in his hour of death. He knows that he cannot stand before God’s justice. God sees through him. It is unpleasant to have guilt pointed out to him. But the prayerful also knows from the beginning: God is just. There is no arbitrariness. The first aria then allows us to look into the conscience of the prayer leader. Two possibilities open up to him: on the one hand, the possibility of the world to form alliances, to lobby, to buy oneself off from the judge with money. On the other hand, the offer to make a friend of Jesus, to enter into a friendship that pays the debt. The possibility of the world is marked as temptation. The final chorale reveals: the worshipper accepts Jesus’ friendship.

Most of us will appreciate this cantata. Its aesthetics are comforting. We can find edification in it. But can we still experience it existentially today, as people did in Bach’s time? Do we still expose ourselves to the presence of God at all? Do we still take time for a memento mori? And if we do, a judge God probably appears for very few of us. Pangs of conscience and shuddering before a God who sees through us are no longer a reality of experience today. Even if God is not exactly dead, he has lost his judging authority for many, even for churchgoers and Bible believers. The sermons today proclaim the so-called “dear God”. On the one hand, I am glad that God’s judgement is no longer a means of bourgeois education. On the other hand, it makes me think that the idea of judgement is disappearing more and more. It wants to say that life is to be seen in the perspective of ethics and justice. The judgement of God means the justice of God. It is meant to prevail, is a critical instance in relation to worldly jurisdiction. It relativises human law and prevents self-righteousness. All the fallen and all the victims long for judges, for a just judgement. How much more should we long for God’s judgement! If we no longer look forward to it, we betray ourselves that we are on the side of the perpetrators. Only offenders shun judge and court.

How fundamentally the primacy of ethics and justice is displaced today can also be seen in the way people turn to the doctrine of reincarnation. For Hindus and Buddhists, rebirth means judgement. In the next life, unpaid debts have to be settled. For many Westerners, however, rebirth is an opportunity to live again. It has degenerated into a fantasy of immortality. Many hardly see rebirth as an ethical judgement anymore.

In our formation as Jesuits, we regularly retreat into silence and solitude. We then do spiritual exercises: Prayers and Bible meditations, review of the day and reflection, examination of conscience and collection, but also breathing exercises, body scanning, etc. This also includes memento mori. One does not only think about one’s own mortality. One visualises one’s own hour of death, places oneself unveiled in God’s presence. For me personally, God’s judgement was not existentially present. I am a person of the 21st century. But I have asked God to see through me where I do not see through myself, to enlighten me where I do not recognise myself, to burn out in me everything that is incompatible with his truth, to remove guilt from me where I do not live up to his justice. I did this exercise for years in my training. In doing so, I always also asked to be able to accept the discomfort or pain involved – for the sake of purification, for the sake of the righteousness and truth that should grow in me. Of course, I cannot say what exactly this exercise has done in me. But I perceived myself more and more free and open-hearted afterwards. We should not impose such exercises on others. And under no circumstances should the justice of the world be the yardstick. So no civic education with spiritual exercises! But we should not let ourselves be deprived of such exercises. How impoverished is a church if it can no longer open up such spiritual spaces. How poor is the secular view of death when it is oriented solely to the functioning of the body without opening up spiritual worlds. A spiritual space, like the one developed by the drama of the Bach cantata, should not be lost to us.

I was existentially touched by the first aria, the strings visualising the trembling and wavering. In addition, the text: ” Indem sie sich untereinander verklagen und wiederum sich zu entschuldigen wagen.” Situations came to life in me in which people begin to accuse each other of things. For a long time, guilt and failure are overlooked, talked down and rationalised away. Suddenly, however, they are brought out and rubbed in one’s face. Such attributions of guilt disgust me. On the surface, they are arbitrary. Looking deeper, they are determined by inner moods, by the suppression of one’s own mistakes and shortcomings, one’s own sin and guilt. People look past each other’s mistakes for a long time, but when one should take responsibility for one’s own mistake, it is warded off by holding one’s weakness up to the other. Yes, it is a fact: those who cannot admit their own guilt imperceptibly project it onto others. If you don’t sweep the rubbish in your house, you unconsciously sweep it in front of the other person’s door. Already in Genesis, Eve shifts her guilt onto Adam. Adam also instinctively passes it on to the snake. In our lives, it is not snakes but scapegoats that have to bear repressed shortcomings and guilt.

Every community, large or small, also creates its scapegoats. Stigmatising victims who are cast out eventually creates social cement. That is practical. This is how a society practices mental hygiene, as it were. Dr Sigmund Freud illuminated the imperial capital Vienna when he wrote of the unease in culture. He knew: every culture has a skeleton in its closet. Each creates its own scapegoats. Can psychoanalysis free us from this, cure us? Yes, to a certain extent. We have to come to terms with our own history of inner alienation. Carl Gustav Jung developed the concept of the shadow. This must be integrated, as must animus and anima. In the battle of the sexes, the repression mechanism of lack and guilt becomes particularly visible. Christian spirituality should integrate such psychological insights and methods. But it also knows that the entanglement goes deeper. Thus, in spiritual accompaniment, in addition to the psychological, the relationship to God and to Christ is also addressed. This can lead to a confessional conversation in the narrower sense. Be that as it may, spiritual coaching is more important today than ever before.

Bach’s cantata knows about the mechanisms of repressed guilt. Whoever is made a scapegoat by society will sooner or later pass on the aggression or strike back. Jesus, however, allowed himself to be made a scapegoat and had the strength to renounce counter-violence. He broke the endless chain of repression and aggression. He freely consented to his execution. Therefore, faith can make sense of the cross of Jesus. It can venerate the cross as salvific and redemptive because it stops the scapegoat mechanism. Moreover, faith sees in the heavenly Jerusalem a society in which the outcast has been reclaimed. The victim is now in the midst of the city as a transfigured lamb. The journey from the outcast scapegoat to the Lamb in the midst is called reconciliation. A society in which this transformation process has taken place no longer needs earthly light, neither sun nor moon. When will the time come when the light of reconciliation shines as brightly as the sun and the moon? I can confess to you: What touches me most in the Easter Gospels is the fact that the Risen Lord does not reproach anyone in the slightest for his failure. No condemnation of the one who was just killed. The Risen One greets the disciples only with, “Peace be with you!” The victim who forgives is as important for reconciliation as the offender’s confession of guilt.

” Kann ich nur Jesum mir zum Freunde machen ” is how the second aria begins. It is the counterpart to the first, which spoke of “suing” and “daring to apologise”. True friendship, reconciled relationships are the remedy. Jesus no longer calls his disciples servants, but friends. The worshipper of our cantata also appears at the beginning as a servant of God. At the end he knows himself as a friend of Jesus. Even the biblical Kohelet sings the praises of friendship. Aristotle devotes an entire treatise to it. We in the Jesuit Order do not call ourselves brotherhood. We call ourselves “friends in the Lord”. Friendship denotes an affective bond and stands for a close relationship. It comes from common interests, grows through shared life. Guilt and weaknesses, mistakes and failures are not blamed on each other. Rather, friends stand up for each other when they are entangled in guilt. And when they have failed, they forgive and start again. Faithfulness is not only the opposite of unfaithfulness. Faithfulness shows itself precisely through weaknesses.

In a digitalised age, such friendships are not easy to live. Social media feeds the illusion that friendships are created with a click. New relationship opportunities that could be even better are always beckoning. Centrifugal forces tug at us. A flood of images and stimuli scatters. These cover our own guilt and shortcomings. How easy it is to flee into entertainment and distraction. But digital networking also makes it possible to maintain relationships across borders and continents. If people invest in long-distance relationships, real friendships can develop there too. Is the person of today also capable of maintaining a long-distance relationship with Jesus? Can Jesus still be a friend who carries you through life? Can a friendship with him still enable us not to shift our own guilt onto others?

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).