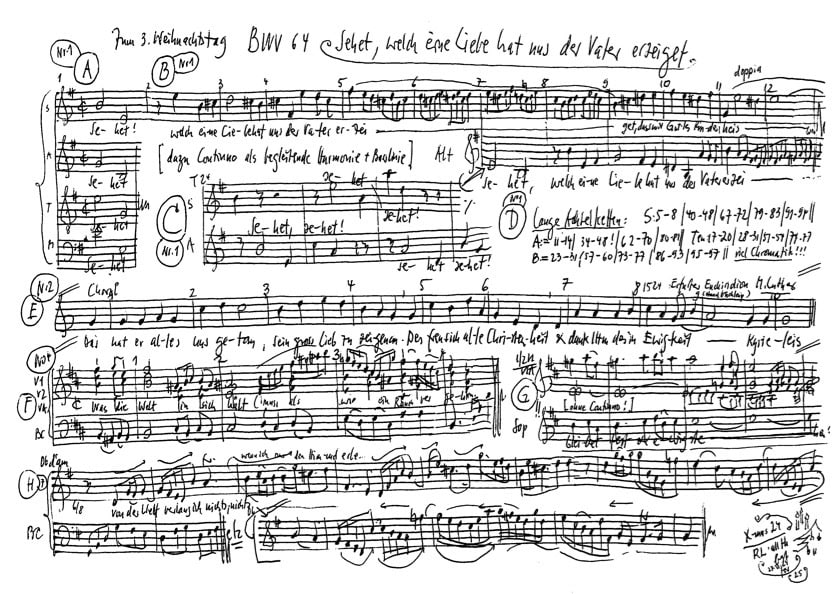

Sehet, welch eine Liebe hat uns der Vater erzeiget

BWV 064 // For the Third Christmas Day

(Mark ye how great a love this is that the Father hath shown us) for soprano, alto and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe d’amore, trombone I-III, cornett, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Alice Borciani, Cornelia Fahrion, Mirjam Striegel, Baiba Urka, Noëmi Tran-Rediger

Alto

Antonia Frey, Stefan Kahle, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Manuel Gerber, Klemens Mölkner, Sören Richter

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, Peter Strömberg, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Elisabeth Kohler Gomez, Olivia Schenkel, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe d’amore

Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Cornett

Frithjof Smith

Trombone

Henning Wiegräbe, Christine Häusler, Joost Swinkels

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Susanne Burri

Recording & editing

Recording date

13/12/2024

Recording location

Trogen (AR) // Evang. Kirche Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

27 December 1723, Leipzig

Text

Movement 1: 1 John 3:1

Movement 2: “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ” (Martin Luther, 1524), verse 7

Movement 4: “Was frag ich nach der Welt” (Balthasar Kindermann, 1664), verse 1

Movement 8: “Jesu, meine Freude” (Johann Franck, 1653), verse 5

Libretto

1. Chor

«Sehet, welch eine Liebe hat uns der Vater erzeiget, daß wir Gottes Kinder heißen.»

2. Choral

Das hat er alles uns getan,

sein groß Lieb zu zeigen an.

Des freu sich alle Christenheit

und dank ihm des in Ewigkeit.

Kyrieleis.

3. Rezitativ – Alt

Geh, Welt! behalte nur das Deine,

ich will und mag nichts von dir haben,

der Himmel ist nun meine,

an diesem soll sich meine Seele laben.

Dein Gold ist ein vergänglich Gut,

dein Reichtum ist geborget;

wer dies besitzt, der ist gar schlecht versorget.

Drum sag ich mit getrostem Mut:

4. Choral

Was frag ich nach der Welt

und allen ihren Schätzen,

wenn ich mich nur an dir,

mein Jesu, kann ergötzen?

Dich hab ich einzig mir

zur Wollust fürgestellt;

du, du bist meine Lust:

Was frag ich nach der Welt!

5. Arie – Sopran

Was die Welt

in sich hält,

muß als wie ein Rauch vergehen.

Aber was mir Jesus gibt,

und was meine Seele liebt,

bleibet fest und ewig stehen.

6. Rezitativ – Bass

Der Himmel bleibet mir gewiß,

und den besitz ich schon im Glauben.

Der Tod, die Welt und Sünde,

ja selbst das ganze Höllenheer

kann mir, als einem Gotteskinde,

denselben nun und nimmermehr

aus meiner Seele rauben.

Nur dies, nur einzig dies

macht mir noch Kümmernis,

daß ich noch länger soll auf dieser Welt verweilen,

denn Jesus will den Himmel mit mir teilen,

und dazu hat er mich erkoren,

deswegen ist er Mensch geboren.

7. Arie – Alt

Von der Welt verlang ich nichts,

wenn ich nur den Himmel erbe.

Alles, alles geb ich hin,

weil ich genug versichert bin,

daß ich ewig nicht verderbe.

8. Choral

Gute Nacht, o Wesen,

das die Welt erlesen,

mir gefällst du nicht.

Gute Nacht, ihr Sünden,

bleibet weit dahinten,

kommt nicht mehr ans Licht!

Gute Nacht, du Stolz und Pracht,

dir sei ganz, du Lasterleben,

gute Nacht gegeben!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Reflection by Susanne Burri on BWV 64

‘See What Love the Father Has Shown Us’

Loving and Letting Go

Can love help us to reconcile with death?

The idea seems strange – anyone who loves and is loved has it good, wants to live, and will almost inevitably see death as an evil.

The author of today’s libretto, a man named Johann Oswald Knauer, points out an important exception: love can reconcile us with death – if it is the love of God. So death and love go together quite well.

In my reflection today, I would like to endorse Knauer’s thesis that love and death go well together. However, I will not focus on the love of God, but will boldly claim that even with worldly love, that is, with love that we feel for other people, we can learn to die. We cannot look forward to death with serenity – I admit that – as worldly lovers. But we can still accept our own death. At least that is my suggestion to you today.

Let us first look at Knauer’s position. For Knauer, the love that matters is

the ‘love that our [heavenly] Father has shown us,’

as it is promisingly stated in the first chorus of today’s Bach cantata. This love, which we may experience as the children of God, is such an uplifting love that it can completely take away our fear of death.

Yes, life is fleeting, as it is also stated in the libretto:

‘What the world

holds within itself,

must pass away like smoke.’

But we don’t need to worry about that, because God loves us so much that he has secured us a heavenly existence at his side. The infinity and glory of this heavenly existence makes the supposed ‘treasures’ here on earth fade away. So we can confidently leave this world behind us.

In the libretto, this point is even further emphasised: because heaven is promised to us, not only does death lose its terror, it even becomes a promise that we can longingly await. The libretto says:

‘Only this, only this

still troubles me,

that I shall dwell in this world a little longer,

for Jesus wants to share heaven with me.’

The reconciliation with death through the love of God, as expressed in the libretto, is thus also a clear turning away from this world, a decisive partisanship for the hereafter and against worldly values. Can we go along with that, with Knauer, with this turning away from the world? What do you think?

If you feel the same way I do, then you initially lack the certainty of a heavenly kingdom, which obviously inspired Knauer, the author of the libretto. However, his turning away from the world remains understandable to me, at least when I focus my attention on certain aspects of my life.

It seems to me that very often I – we – are caught in a web of tasks, deadlines and appointments, most of which are not really important, but which present themselves as non-negotiable in our daily lives and leave us with neither the time nor the leisure to devote ourselves appropriately to what really matters to us.

When I visualise this hamster wheel, it is easy for me to go along with Knauer’s turning away from the world: of course a divine promise of true and eternal values seems attractive from the perspective of the hamster wheel.

But the hamster wheel, or the question of how we can better deal with the pressure to perform and succeed, is not the only thing that shapes our lives. What matters just as much to many of us, probably most of us, and gives our lives a thoroughly positive meaning, is our relationships with other people – other people we love.

When Knauer speaks of the ‘distress’ of having to dwell in this world a little longer, it seems extremely strange when we think of loved ones – and of the relationships that enrich our lives. ‘Doesn’t he have any friends, the poor devil, that he so desperately longs for death?’ one wonders, and immediately pictures Johann Oswald Knauer sitting alone and isolated in a little room, writing librettos to himself.

However, if we want to hold on to the value of human relationships, perhaps especially against Knauer, then the question arises as to whether this prevents us from reconciling ourselves with our own mortality. At least at first glance, this seems to be the case. How could it not be the price of loving worldly relationships that they resent death? When we love other people, we connect with them and with life – and can only perceive our own death as a threat.

Over the millennia, many philosophers have repeatedly emphasised that our fear of death causes a great deal of harm and stands in the way of human happiness. If these philosophers are right, then the price that apparently has to be paid for worldly love is an extraordinarily high one.

But fortunately, what seems so obvious is not at all clear. I am convinced that true love has a lot to do with properly understood letting go. Those who truly want to love must always accept that what is most important to them is beyond their sphere of influence. And those who can accept this loss of control, this powerlessness, can also deal with their own mortality.

Perhaps you have already heard what the prophet of Khalil Gibran teaches us about children.

The prophet says:

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of life’s longing

for itself.

They come through you, but not from you,

and though they are with you, they do not belong to you.

You may give them your love,

but not your thoughts,

for they have their own thoughts.

You may house their bodies,

but not their souls,

for their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow,

which you cannot visit,

not even in your dreams.

With Gibran, I am convinced that the loving attitude we should try to cultivate towards our children is one in which we are privileged to accompany our children for a while.

As good parents, we do not rule over our children: we do not pursue our own rigid plans for them or through them. Instead, we try to show our children possibilities and create spaces for them to find and follow their own path.

As good parents, we also recognise – and this is perhaps the most difficult lesson – that no matter how important it is to us, we cannot bring about our children’s happiness, and we certainly cannot force it. We reach important limits early on, much earlier than I would have expected as a mother.

These limits exist not only as limits to what is feasible, because we are neither omnipotent nor omniscient. They also exist because children are independent persons. Thus, respect for our own child often requires us to withdraw, even if the limits of what is actually feasible have not yet been reached.

Those who love a child are there, they care and protect. But they often also take a step back, and they do that because they love. This does not mean that our children are not our children.

And once we have come to terms with this beautiful idea, it also makes sense that other people do not belong to us either. Our friends and our partners are not ours, we do not own them.

When we love another person, we recognise and appreciate them as an autonomous other – we form a connection with someone, but we don’t want to make them our own, we don’t want to control and define them, and we don’t want to control and define them: we love the other person in their freedom.

This kind of loving that lets go is often something inspiring and sublime, not only for the beloved, but also for the lover: full of wonder and gratitude, we realise that we are actually selflessly devoted to a cherished, fascinating other.

Max Frisch describes the inspiring side of this letting-go love in his diary from 1946 to 1949. He says:

‘It is remarkable that we can say the least about the person we love, what he or she is really like. We just love them. After all, that is what love consists of, the wonderful thing about love, that it keeps us in the balance of being alive, in readiness to follow a person in all their possible developments.’

But loving the other as a free being is not always easy. On the one hand, the other person can also develop in such a way that they move away from us, which can be painful. But even without such a turning away, loving letting go is often difficult.

As lovers, we always want to protect and preserve. This impulse to hold on and control is part of love. Loving letting go means to stop this impulse at the appropriate point, without wanting to eliminate or extinguish it. If the impulse were extinguished, we would no longer be lovingly turned towards the other. As lovers, we therefore let go, even though a part of us also wants to hold on. Loving letting go is based on the deep insight that we cannot control, that we cannot and should not preserve what is so close to our hearts. This insight may also make us feel wistful from time to time.

When we practice loving letting go, we also practice accepting our own mortality. The movement, it seems to me, is the same. We realise that we can neither control nor should we what is so important to us. So we cannot hope that loving detachment exercises will one day make us indifferent to our own death. The loving detachment I have tried to describe goes hand in hand with feelings – even big, ambivalent feelings.

Of course, we can all hope for eternity, as Knauer says. But I hope and trust that it can also be dealt with constructively, given our limitations. Let us try to give this-worldly love and appreciative letting go a chance – in the firm belief that our hearts are big enough for it.