Wer weiß, wie nahe mir mein Ende

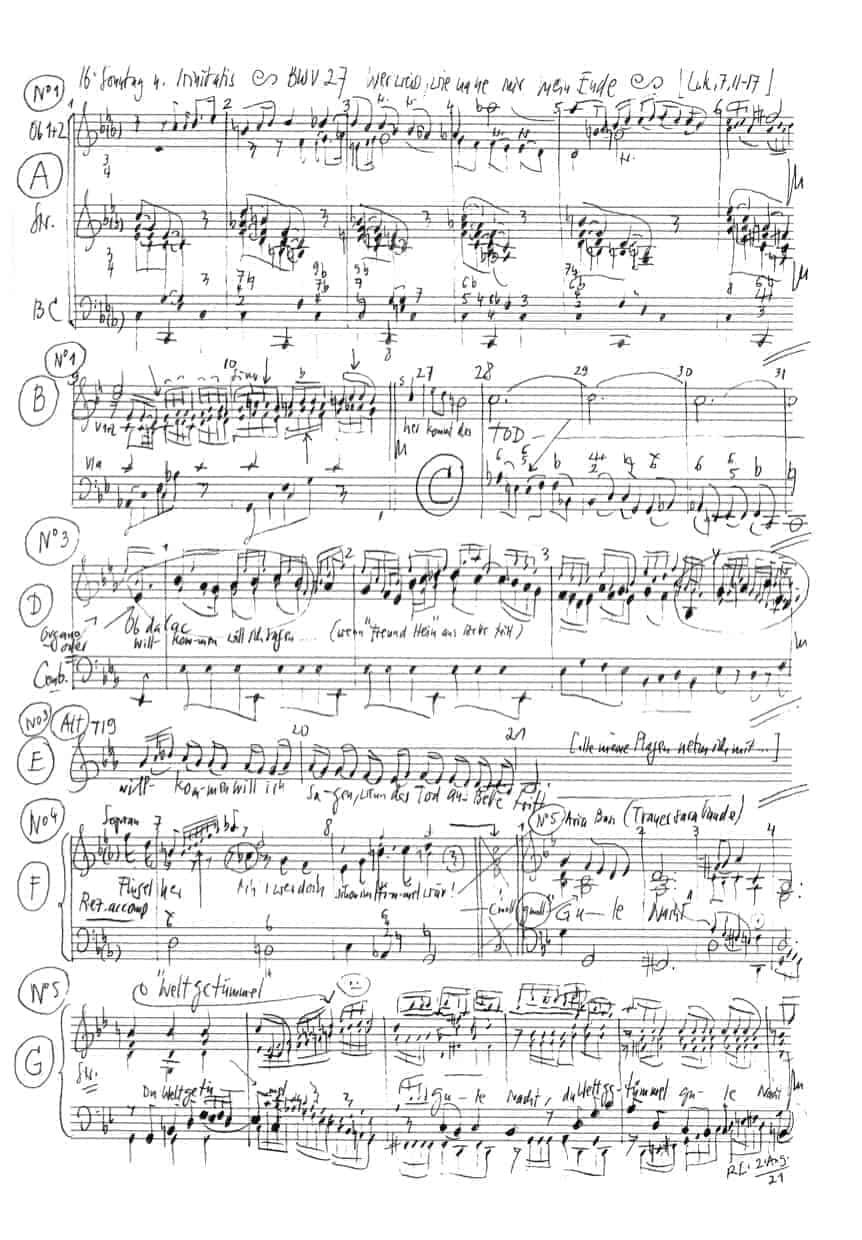

BWV 027 // For the Sixteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Who knows how near to me my end is?) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass; vocal ensemble, horn, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Herr, Gott, du bist unsre Zuflucht für und für. Ehe denn die Berge wurden und die Erde und die Welt geschaffen wurden, bist du, Gott von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit, der du die Menschen lässest sterben und sprichst: «Kommt wieder, Menschenkinder!» Denn tausend Jahre sind vor dir wie der Tag, der gestern vergangen ist, und wie eine Nachtwache. – Lehre uns bedenken, dass wir sterben müssen, auf dass wir klug werden.

Darum bitte ich, dass ihr nicht müde werdet um meiner Trübsale willen, die ich für euch leide, welche euch eine Ehre sind. Derhalben beuge ich meine Kniee vor dem Vater unseres Herrn Jesu Christi, der der rechte Vater ist über alles, was da Kinder heisst im Himmel und auf Erden, dass er euch Kraft gebe nach dem Reichtum seiner Herrlichkeit, stark zu werden durch seinen Geist an dem inwendigen Menschen, dass Christus wohne durch den Glauben in euren Herzen und ihr durch die Liebe eingewurzelt und gegründet werdet, auf dass ihr begreifen möget mit allen Heiligen, welches da sei die Breite.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Maria Deger, Jessica Jans, Simone Schwark, Noëmi Sohn, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Isabelle Stettler, Jan Thomer

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Joël Morand, Sören Richter, Walter Siegel

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Valentin Parli, Daniel Pérez, Retus Pfister, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Andrea Brunner, Elisabeth Kohler, Rahel Wittling, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Horn

Thomas Friedländer

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Laura Alvarado

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Ina Schmidt

Recording & editing

Recording date

20/08/2021

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

6 October 1726, Leipzig

Text

Ämilie Juliane von Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt (movement 1); unknown source (movements 2–5); Johann Georg Albinus (movement 6)

In-depth analysis

BWV 27, composed for the Sixteenth Sunday after Trinity in 1726, numbers among the chorale cantatas written by Bach after completing his annual cycle of 1724/25. Although the librettist remains unknown, the introductory chorus is based on a hymn penned by Countess Ämilie Juliane of Schwarzburg- Rudolstadt (1637–1706), a noblewoman of the imperial estate.

The introductory chorus is characterised by three elements that make up the orchestral opening: a low keynote in broken octaves that provides for a weighty foundation, descending arpeggio sequences in the strings and a haunting oboe duo that punctuates the sarabande- like music with a series of sighs and dissonant accents, evoking a poignant scene of suffering. Thus furnished with an end-of-days backdrop, the choir then commences its unadorned chorale, whose grim prophecy of a “near end” is interpolated with recitative-style passages in which the individual voices either respond to the hymn text (“das weiss der liebe Gott allein” – This knoweth God the Lord alone) or rephrase it in their own words. Through its stark contrast to the despondent undertone of the setting, this exchange of voices emphasises the urgency of the message while also pointing to the opportunity for humans to act piously and make a humble contribution to their own destiny. In this setting, Bach has realised nothing short of a “St Mortal Passion”, which, without offering superficial solace, closes in the sombre key of C minor.

The ensuing tenor recitative, supported by only a sparse continuo line, poses an audible challenge to the soloist, who must be always “zum Grabe fertig und bereit” (for death’s grave ready and prepared). Indeed, the praiseworthy maxim “Ende gut macht alles gut” (For all is well that endeth well) goes hand-in-hand with the weighty resolution to constantly behave as if each day were the last – the ultimate test of a godly life.

In keeping with his practice of accentuating heightened emotional states through unusual instrumentation, Bach employs in the following aria an alto voice combined with the distinctive timbres of an oboe da caccia and an obligato organ part to illustrate the narrative of the soul’s purification and its yearning for the afterworld. Here, the writing for these instruments is typical of Bach: for the oboe da caccia, a lyrical cantilena that anticipates the vocal lines, and for the organ (although probably a harpsichord at the first performance) gleaming lines of running passages and broken chords. As a result, there is a constant juxtaposition of repose and restlessness that encapsulates the whole gamut of emotions sparked by considering one’s own death – from joyous anticipation to resigned acceptance. Nevertheless, like the encouragement from a good pastor, the demonstratively pre-emptive da capo of the “Willkommen” (welcome) motto ultimately allows the spirit of resolve to retain the upper hand.

With the soprano recitative “Ach, wer doch schon im Himmel wär” (Ah, who would now in heaven be), Bach once again changes scenes and, following the valiant “whistling past the graveyard” of the previous aria, opens a skylight to the horizon of higher freedom that comes from making clear resolutions. Here, this vision of becoming one with the divine lamb in the bliss of heaven gradually builds to an exclamation of “Flügel her!” (Wings come now!), which succeeds in breaking through even the rigid ceremony of the accompanying string setting.

The bass aria returns the protagonists back to the fray of earthly life. The constant alternation of rapture and down-to-earthiness captured by descending circling figures versus breathless, repeated semiquavers represents a touching portrayal of the conditio humana of a good Christian who is at once still fully here and yet already elsewhere. While it may be coincidence that the motifs and musical flow echo two key passages of the St John Passion – “Bei der Welt ist gar kein Rat” (In the world there is no help) and “Der Held aus Juda siegt mit Macht” (The man of Judah wins with might) – they are nevertheless an apt depiction of the inner turmoil portrayed in this ambiguous piece.

For the closing chorale, Bach has saved a trump that pays equal tribute to Leipzig’s hymn tradition and the practices of the Thomas School. Indeed, rather than writing his own setting for the text, Bach employs a five-voice rendition composed by Johann Rosenmüller for the funerals of two daughters of Abraham Teller, Leipzig’s archdeacon, in 1649 and 1652. This seemingly simple occasional piece was evidently so valued that it was included in Gottfried Vopelius’s “Neu-Leipziger Gesangbuch” (New Leipzig Hymnal) of 1682; later, in 1719, it was used by Johann Kuhnau, Bach’s predecessor as Thomas Cantor, as the basis of a cantata chorus. And just as Bach himself paid reverence to the enchanting beauty of this piece by retaining its mensural notation in the closing two lines, we too have duly celebrated the setting by inserting some repeats and passages of consort playing.

Libretto

1. Choral und Rezitativ — Sopran, Alt, Tenor

Wer weiß, wie nahe mir mein Ende?

Sopran

Das weiß der liebe Gott allein,

ob meine Wallfahrt auf der Erden

kurz oder länger möge sein.

Hin geht die Zeit, her kömmt der Tod.

Alt

Und endlich kommt es doch so weit, daß sie zusammentreffen werden.

Ach, wie geschwinde und behende

kann kommen meine Todesnot!

Tenor

Wer weiß, ob heute nicht mein Mund die letzten Worte spricht! Drum bet ich alle Zeit:

Mein Gott, ich bitt durch Christi Blut,

machs nur mit meinem Ende gut!

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

Mein Leben hat kein ander Ziel,

als daß ich möge selig sterben

und meines Glaubens Anteil erben;

drum leb ich allezeit

zum Grabe fertig und bereit,

und was das Werk der Hände tut,

ist gleichsam, ob ich sicher wüsste,

daß ich noch heute sterben müsste;

denn: Ende gut, macht alles gut.

3. Arie — Alt

Willkommen! will ich sagen,

wenn der Tod ans Bette tritt.

Fröhlich will ich folgen,

wenn er ruft in die Gruft.

Alle meine Plagen

nehm ich mit.

4. Rezitativ — Sopran

Ach, wer doch schon im Himmel wär!

Ich habe Lust zu scheiden

und mit dem Lamm,

das aller Frommen Bräutigam,

mich in der Seligkeit zu weiden.

Flügel her!

Ach, wer doch schon im Himmel wär!

5. Arie — Bass

Gute Nacht, du Weltgetümmel!

Jetzt mach ich mit dir Beschluß,

ich steh schon mit einem Fuß

bei dem lieben Gott im Himmel.

6. Choral

Welt, ade! Ich bin dein müde,

ich will nach dem Himmel zu,

da wird sein der rechte Friede

und die ewge stolze Ruh.

Welt, bei dir ist Krieg und Streit,

nichts denn lauter Eitelkeit,

in dem Himmel allezeit

Friede, Freud und Seligkeit.

Ina Schmidt

“Who knows how near to me my end is?”

When I heard this particular death cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach for the first time, I was surprised by the lively power that this piece radiated – as if the music wanted to counteract the worry about one’s own finitude with something, something that dares to engage with this unawareness of one’s own transience and finitude.

And yet, at the same time, there was a scepticism, a probing and doubtful detachment towards this courageous venture: can we oppose our own finiteness at all, is not the thought alone hope and longing?

Or can we just no longer do it today? Is it because in the 18th century it was still possible to cultivate a different approach to death and dying, the echo of the ars moriendi – the art of dying – which originated in the Middle Ages? At that time, such an art was not intended to drive death out of life, but to ensure that we could prepare ourselves for a dying that we could accept as good.

So can death be “tamed” in this particular artful way? The French cultural historian Philippe Aries was certain that death in earlier epochs had been just such a “tamed” death, embedded in ceremonies and world views, religious beliefs and ideas that weave a cultural texture out of words and melodies, out of thoughts and poetry, in which people can settle, but which today we often dismiss as nebulous illusions, narratives or “biases”, enlightened and secularized, as we try to explain death to ourselves today.

But precisely because of this, according to Aries, we do not keep our own finiteness at bay; all medical and technical progress often only results in the tamed death becoming a feral death – behind drawn curtains, lonely, alone with flashing devices and tubes that are supposed to defend life against dying. In all our knowing and explaining, we ultimately lack what is also found in the text of the Dying Cantata: Faith in something that can give us another form of living certainty, trust in something greater than ourselves – and thus enable a lived habit with a death that will come to us at some point, that will not lose its terror, but that we can bear.

End pieces

Surrounded by all these doubts and probing questions, I remembered the poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Schlussstück,” words that have long been meaningful to me: “Death is great, we are His laughing mouth – when we mean ourselves in the midst of life, He dares to weep, in the midst of us.”

Over twenty years ago, these lines were part of an obituary with which my husband and I tried to say goodbye to a good friend. He had died suddenly, of an infection, supposedly nothing serious – in the middle of life, just become a father, about to get married, his father said at the funeral: “We were all so happy just now.”

I remember how, after his death, I entered for the first time the apartment that was actually so familiar, where we had so often cooked, celebrated and thought about all the important and unimportant things in life. His shoes were still in the hallway, everything seemed the same, and yet there was an emptiness, an absence in those rooms that made everything seem strange, everything so much bigger and me so much smaller.

In the face of death, we are struck by the realization that death is near and yet we cannot grasp it – this knowledge that this nearness does not have to be significant only at the end of a long life suddenly breaks through with full force. We are transient beings, from the moment we are born we are heading towards an end we cannot know. We know the “that” but not the “when.” No one can know “how near my end” is, or how many times I may have been near death. One’s own or that of another loved one with whom we have just sat, “Who knows if today my mouth will not speak the last words?”

This ignorance is ambivalent. It protects us, the idea of a future in which death is still far away helps us to accept life as a precious gift and to fill it with deeds, desires, experiences and goals. And yet, not infrequently, we have to be aware: In the midst of life, death dares to cry within us. This experience is impressive and painful, but it also shakes us awake, makes us aware of the value of life in a different way and sometimes even raises new questions “laughing mouth”.

But how can we bear this tension and uncertainty? How can we love people and make sense, when we dedicate ourselves to these thoughts in all clarity? Meaningless and absurd seems a life that does nothing but end? And yet we are beings full of hope for a good, successful and long life, in which we create something that could remain even if everything comes to an end.

The art of embracing these supposed contradictions and accepting laughter and crying side by side, perhaps even simultaneously, is no easy task, but we are capable of it. We come into the world as finite beings, born into an uncertain future, and the closer we are to that beginning, the more self-evident this knowledge seems: Not only are we finite, but we are also “initial”; every ending holds a beginning, even if we cannot know it. If we talk to children about death, we might be surprised how wise and natural the way these little people and young minds often deal with transience is – they are much less interested in distinguishing between life and death, but know about the conditionality of the two – even if they cannot always put it into words. The fact that tears flow in the process is no reason not to try and – at some point the sun will shine again, as I was able to learn from a 12-year-old thinker. Can we learn to let death into our lives, or rather practice taming it in our own and new way?

To philosophize is to “learn to die.”

The thinker Michel de Montaigne considered philosophy to be the intellectual activity that could help us in this endeavor, that is, actually teach us how to die. In his famous essay “To philosophize is to learn to die”, the philosopher asks: “The goal of our career is death – our eyes are inevitably fixed on it. How, when it strikes fear and terror into our hearts, can we take even one step forward without shuddering?” To this, for Montaigne, there can be only one answer: We must try to invite death to us and thereby take away its terror – this, he said, is the only way not to save ourselves to a redemptive afterlife, but to live a truly good life. But the philosopher did not mean the attitude alluded to in the cantata of being ready to die at any time and living in anticipation of death, but rather to exhaust one’s own life powerfully and presently and yet to listen when death begins to cry in us now and then. To invite him in, even when it hurts and frightens us, like a kind of spiritual “nevertheless”: “Let us rob him of his unearthliness, let us keep company with him, let us become accustomed to him, let us consider nothing so often as him.”

This idea sounds like something we can try. But not everyone agrees with Montaigne on this: The philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch, for example, is firmly convinced in his work “Death” that we “decidedly cannot get used to death.” It always hits us suddenly in all its harshness and in all its preparation. According to Jankélévitch, one’s own finiteness remains one of man’s greatest mortifications.

I, too, am sure: most of us have had experiences in which we were inconsolable and certainly did not want to practice getting used to death. But does that make it synonymous with mortification? Can’t mortification only come from a disappointed expectation, and what exactly can an expectation of life look like? What exactly does life owe us if we may resent its own impermanence? Yes, the end always strikes us unawares, “despite our precautions,” as Jankélévitch points out, but a successful life is not about preventing death, but about the possibility of living with it-without despairing of it forever. It is about finding comfort and support in something that may thereby be a promise, because it goes beyond us and our own lives.

Life in the face of death

And is this not also what Bach is trying to do in his music? To enable consolation in the face of death, not to find words like Rilke or Montaigne, but to use music as a language to create support and forms of expression that allow a “nevertheless” to be imagined and felt. A nonetheless that also lies in questionability, a questionability so radical that it can become a possibility again. A life does not become worthless and meaningless by the fact that it comes to an end at some point. On the contrary, it only lives in this state of tension of coming and going, of beginning and end, and human beings are probably the only beings capable of consciously engaging with this knowledge: Only we live a life in the face of death, if we choose to do so.

At the end of all these reflections there may indeed be the wish, as it says in the cantata, that one’s own end may be a “good” one, for “all’s well that ends well”.

The end of a fulfilled life, in which we are not suddenly torn from our own midst, but a life from which we can take leave – world-weary and life-full – and perhaps no longer have to endure this, but can even want to. I hope, very much, that our friend, who was not at all tired of life and full of the world, and who hoped for a future that was yet to be shaped, was also able to find this peace at that time. A peace that perhaps cannot be an earthly one and that for us, who reflect on it here, is only alive as a question and a possibility. A question we can ask ourselves, together with words and in music – but then we are already on the way to doing exactly what Montaigne wished for so much: To take away the horror of death by inviting it to us – in all the unknowing of the end that will eventually come to us.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).